www.thegospelcoalition.org

Why I Changed My Mind on Mixed Martial Arts

I used to love mixed martial arts (MMA)—the submissions, the knockouts, the five-round wars—all of it. And I didn’t just love it from the couch. I’ve spent years on the mats. As a Brazilian jiu-jitsu black belt, I deeply appreciate the skill, dedication, intelligence, and sacrifice that go into training for martial arts. Professional MMA fighting—a full contact sport that combines techniques from multiple combat styles—is another thing entirely.

When I say I loved MMA, I mean it. I admired (and still do) a fighter’s work ethic, physical courage, and creativity under pressure. But in a single moment while watching a fiercely contested match, I changed my mind about MMA.

I saw a fighter get knocked unconscious.

That moment was problematic enough on its own. It’s hard to square the intentional infliction of brain injury with the biblical call to love our neighbor. But as I sat there watching the fighter’s limp body on the mat, I heard the crowd erupt in applause. I looked up and saw their faces as they celebrated the outcome. That’s when I realized: MMA isn’t just a sport; it’s a spectacle. It’s human-on-human violence for profit and entertainment.

View Violence Biblically

As soon as sin entered the world, violence entered with it—Cain rose up and killed his brother Abel (Gen. 4:8). From that point on, the earth has been “filled with violence” (6:11). This simple observation clues us in to the fact that violence isn’t morally neutral; it’s one of the earliest and clearest fruits of the fall.

Violence isn’t morally neutral; it’s one of the earliest and clearest fruits of the fall.

Certainly, Scripture recognizes that violence is sometimes necessary in a fallen world (Ex. 22:2–3; Rom. 13:4). Even so, we should see violence as a tragic necessity, not a spectacle for pleasure and profit—which is exactly what professional mixed martial arts has become.

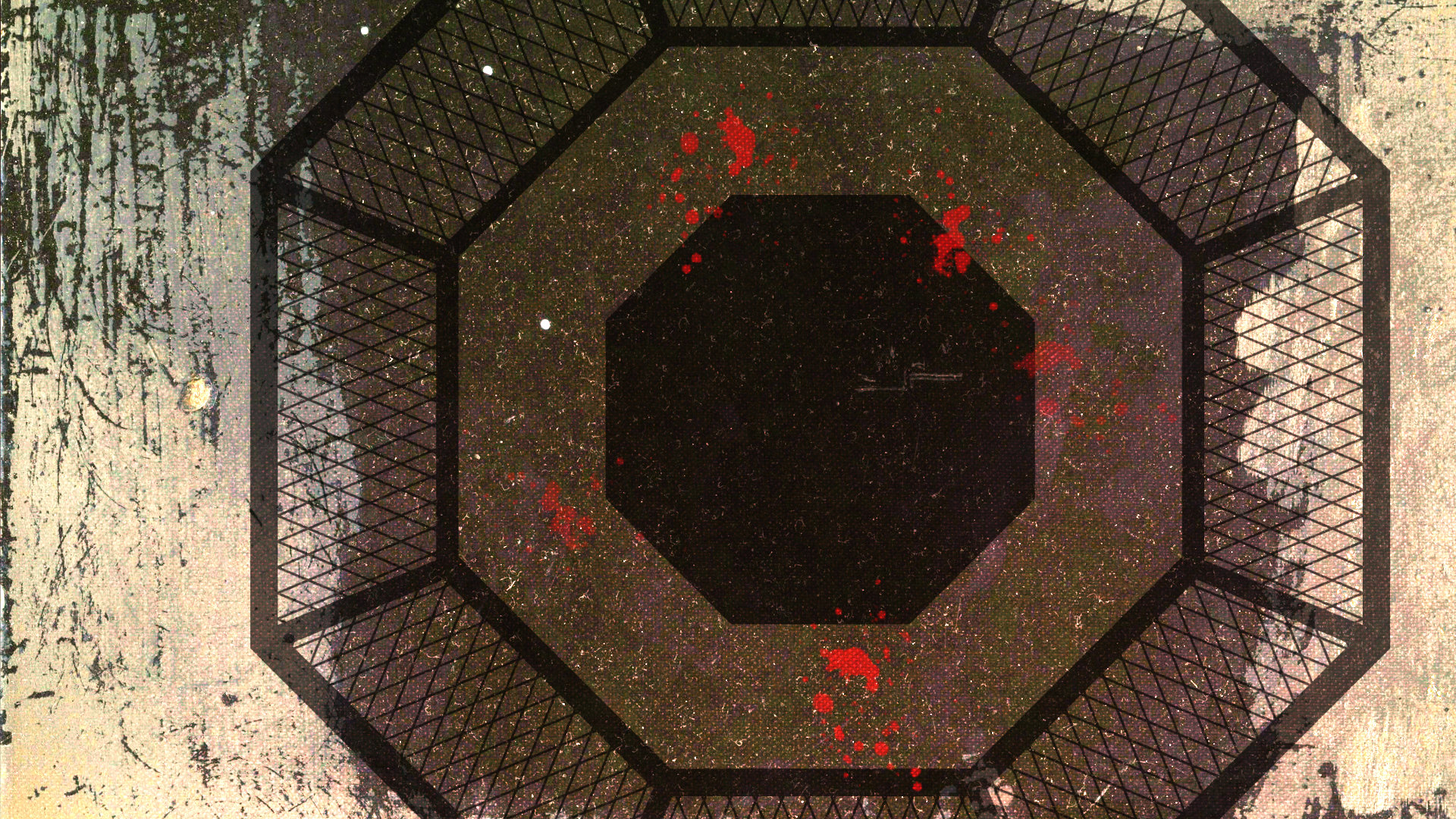

Many people have never experienced the violence of MMA firsthand, so they may have trouble comprehending just how brutal the sport really is. But pause for a moment and think about what’s taking place in that octagon: Men and women are striking each other with the specific aim of causing significant bodily harm. Every punch, every kick, every armbar is meant to crush, tear, or break.

Imagine you’re sitting cage-side at a Ultimate Fighting Championship event. The bell rings, the crowd roars, and within seconds, a fighter’s nose is broken and blood is streaming down his face. A shin crashes against a rib cage, and you hear the dull thud of bone on bone as the fighter’s rib fractures. An ACL tears as one fighter kicks another in the side of the knee. The referee hovers, waiting to see if the opponent can still defend himself. And all the while, the audience cheers.

This isn’t training, where partners work with restraint and respect. These fights are all-out competitions, where the reward goes to the fighter who can hurt his opponent the most. It raises questions about what moral good this sport exhibits.

Gladiatorial Echoes

Modern Christians aren’t the first to have asked questions about the value of violent sports. According to church tradition, a monk named Telemachus entered the Roman arena in the early fourth century to stop a gladiatorial fight. His opposition to the event wasn’t due to squeamishness but because the spectacle commodified violence and turned crowds into bloodthirsty mobs. Thus, when he tried to intervene, the enraged crowd stoned Telemachus to death. His act of conscience so shocked the emperor that the games were soon abolished.

Professional MMA isn’t identical to the Roman arena, but the parallels are sobering. We should carefully evaluate what happens to our souls when our entertainment depends on the injury of human beings made in God’s image. Just as we question our culture’s notion that consent is a sufficient basis for a sexual ethic, so we should ponder whether an image-bearer consenting to potential injury or death can make such violence permissible.

We should carefully evaluate what happens to our souls when our entertainment depends on the injury of human beings made in God’s image.

I’ve raised my concerns about the violence of MMA publicly before. Some have questioned whether the same concern should be applied to the violence of a sport like football. In my view, that’s a false equivalence.

American football involves violent collisions and real injuries; Christians should certainly think carefully about the game’s ethical boundaries. Even so, football and MMA are fundamentally different. The goal of football is to advance a ball and score points. Injury is a risk, not the primary purpose of the sport. When a player gets a concussion it’s a bug, not a feature, of the game. Over the past decade, the NFL has made significant rule changes to improve player safety. The fan culture has also changed, with spectators now more likely to respond with concern for an injured player rather than a celebration of the violence of the hit that knocked him unconscious. In contrast, in MMA, causing your opponent pain is the purpose of the sport.

Good of Martial Arts

I can personally attest to much of the good in martial arts training. It builds discipline, humility, respect, and resilience. In a gym setting, sparring is controlled, safety is prioritized, and the goal is skill development, not bodily harm. Moreover, martial arts training can help someone defend those who can’t defend themselves (Ps. 82:4), a laudable goal.

But professional competition is different. The incentives shift. Fighters are rewarded for hurting their opponents. Promoters market the spectacle as modern gladiatorial combat. Some fighters see themselves as gladiators.

Audiences pay to see people get hurt. According to one study, 57 percent of MMA matches had at least one reported injury. A more recent systematic review indicates that around 15 of 100 fighters experience a concussion during a match (usually the loser). Spectators crave short, decisive matches. As one commentator notes, “Whether it’s a jaw-dropping knockout or a bone-crushing, suffocating submission, fans crave a decisive finish.” In 2024, only a little over half of UFC fights went the full duration. There’s something fundamentally different about this sort of competition from the training that occurs in a local gym.

Self-Examination

Not everyone will come to the same conclusion about the morality of MMA as a sport. However, it’s worth considering the forms of entertainment we consume.

1. Examine our appetites. If we find pleasure in another person’s pain, we should ask, Is there anything godly in this joy?

2. Distinguish wisely. We shouldn’t lump all contact sports together. Rather, we should ask, What’s the purpose? What’s the spectacle? What’s the cost? Christians should celebrate sports and disciplines that form strength, courage, and endurance without commodifying harm.

3. Exhort with gentleness. Some Christians will see no issue with MMA. Several vocal Christians are among the ranks of professional fighters. Though I’m fully convinced of my position, it may take time for others to understand the problems involved in MMA. The way forward is nuanced conversation, not condemnation.

I once defended the manly virtues of MMA. I’ve rolled thousands of hours on the mats and still value the discipline of martial arts in a fallen world. But my conscience has shifted. Christians shouldn’t retreat from sport or strength but redeem them—we should love skill, discipline, and courage without celebrating injury.