www.thegospelcoalition.org

What Wicca’s Origins Teach Us About Christian Nationalism

In 1921, an Egyptologist named Margaret Murray accidently invented a religion.

Murray wrote a book and an Encyclopaedia Britannica entry that claimed the witch trials of the 16th and 17th centuries had targeted real witches, a surviving pre-Christian fertility cult who worshipped a horned god. Historians who actually studied the trials thoroughly debunked the theory.

Yet people who believed Murray’s invented history started acting as if this spiritual movement was real. The British occultist Gerald Gardner even claimed he was initiated into just such an ancient coven. What he actually did was build a new religion from Freemasonry, ceremonial magic, and Murray’s fabrications. He called it witchcraft. We call it Wicca.

As sociologist Gabriel Rossman explains in a recent review, Murray’s theory became “performative”: It wasn’t true when she wrote it, but people who believed it made it true by acting as if it were.

We see something similar happening today with Christian Nationalism.

Inventing a Christian Nation

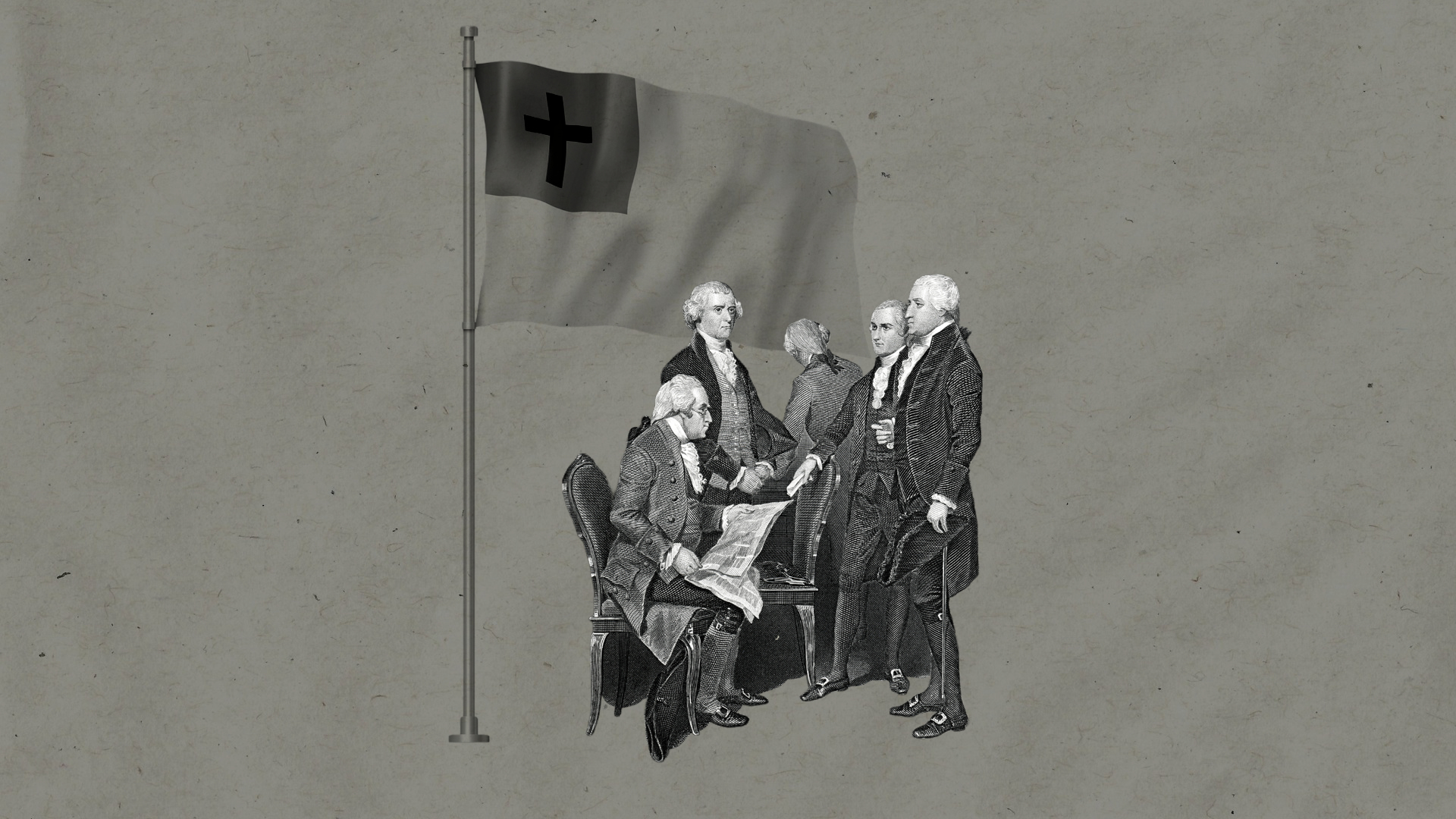

Just as Gardner drew on Murray’s debunked scholarship to create Wicca, many Christian Nationalists draw on equally dubious historical claims to construct their vision of America’s past. The most prominent example is David Barton, whose work has been so thoroughly discredited that his Christian publisher, Thomas Nelson, withdrew his book The Jefferson Lies in 2012 after historians—including conservative evangelical historians—documented its errors.

Barton’s narrative is that the founders were devout Christians who intended America to be an explicitly Christian nation, and that we’ve simply fallen away from their vision. If we can return to that original design, we can restore Christian America.

The problem, of course, is that version of America never existed. The key founders’ actual beliefs were often far from orthodox Christianity. Jefferson famously produced his own Bible by cutting out all the miracles. Franklin, in his autobiography, admitted that while he believed in God, he “seldom attended any public worship.” Washington, despite his public religiosity, conspicuously avoided taking Communion and never explicitly affirmed Christ’s divinity.

That version of America never existed. The key founders’ actual beliefs were often far from orthodox Christianity.

This isn’t to say America was secular in the modern sense. The culture was thoroughly Protestant up until the late 1960s. Christianity shaped the assumptions, informed the moral reasoning, and provided the language used to talk about civic life. As Kevin DeYoung helpfully distinguishes: America was “demonstrably Christian” without being “officially Christian.” Naturally, we should prefer a nation where genuine gospel-centered Christianity is influential and allowed to flourish freely. But that isn’t the same as a nation where the state enforces Christianity.

Like the neo-pagans who adopted Murray’s imagined past as their own, many Christian Nationalists are now trying to “restore” an America that exists primarily in their imagination. And in so doing, they’re creating something genuinely new that smuggles in much that’s harmful about nationalism while discarding what makes Christianity beautiful.

Strange Birth of a Label

It might be difficult for younger people to grasp, but until roughly 2013, virtually no one in America self-identified as a “Christian Nationalist.” The term existed primarily as an academic category and was often used (and still is used) as a pejorative by sociologists and critics.

Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that the Greatest Generation (those who were born from 1901 to 1927 and fought in the world wars) had to die off before the label could be adopted. The generation of Americans who’d fought against actual nationalist movements would have been as discouraged to hear their children and grandchildren calling themselves “nationalists” as they’d be to hear they’d become “fascists.”

As DeYoung notes, until recently, “no one was actually arguing for something called Christian Nationalism.” Whatever one might have called the constellation of beliefs about Christianity and American politics, it wasn’t that. The label was adopted from critics and then embraced, like wearing an insult as a badge of honor. It’s similar to how many people, around the same time, embraced the related designation of “socialist.”

The reason the label matters is that “nationalism” isn’t a neutral term. It refers to a specific political ideology that emerged in the late 18th and 19th centuries, shaped by Marxism and ethnic and racial conflicts. Nationalism requires a story of “Us” and “Not-Us.” The two most common framings are the Marxist “oppressor and oppressed” model (with nationalists seeing themselves as the oppressed) and the Nazi Carl Schmitt’s “friend-enemy” distinction. In these views, a political community exists only insofar as it can distinguish its friends/oppressed (us) from its enemies/oppressors (them).

One of the most significant problems with nationalism is that it requires subsuming other loyalties (such as family, church, and local communities) to allegiance to the nation. As political theorist David Koyzis has documented extensively, nationalism in this technical sense makes the nation an object of ultimate loyalty. The nation becomes a functional idol that demands sacrifice and devotion.

When Christians casually adopt the “nationalist” label without understanding its ideological content, they’re signing up for a package deal they may not realize they’re buying.

Why Nationalism Contradicts Christianity

The fundamental problem with nationalism—in its precise ideological sense—is that it divides humanity along lines the gospel erases. The apostle Paul declared that in Christ “there is neither Jew nor Greek” (Gal. 3:28). The church is explicitly transnational and multiethnic, drawn from “every nation, tribe, people and language” (Rev. 7:9, NIV).

The fundamental problem with nationalism—in its precise ideological sense—is that it divides humanity along lines the gospel erases.

Christianity can and should inform a Christian’s political engagement, including love of country. But nationalism as an ideology tends to invert the proper order. Instead of the nation serving as one legitimate sphere of life under God’s sovereignty, it becomes the ultimate community demanding supreme loyalty over all other loyalties, such as one’s family and local church.

Koyzis distinguishes between healthy patriotism (i.e., a love of one’s particular place and people) and ideological nationalism, which absolutizes the nation and its interests. A Christian can (and should) be patriotic. A Christian cannot, without contradiction, be a nationalist in the ideological sense.

This is why the “Christian Nationalist” label is so poorly chosen. It yokes together a universal faith with a particularist ideology in a way that distorts both.

Why Nationalism Contradicts Americanism

Nationalism doesn’t just contradict Christianity; it contradicts the American founding.

The Declaration of Independence grounds human rights in universal truths: “all men are created equal,” and they’re “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.” While this document was written to and for Americans, the truths it proclaims apply to all humanity. The genius of the American experiment was precisely its universalism, its appeal to principles that transcended blood and soil.

Nationalism, by contrast, is built on ethnicity, language, shared ancestry, and cultural homogeneity. This is the opposite of Americanism. Our country was founded on propositions, not bloodlines. Our unofficial motto is E pluribus unum (from many, one), which describes a nation constituted by ideas rather than by “heritage.”

When some Christian Nationalists appeal to European ethnic identity or worry about demographic changes in ways that prioritize ancestry over creed, they’re not recovering some lost American essence. They’re importing a neo-Marxist European ideology that the American founding explicitly rejected and tried to protect us from.

Dangerous Destination

Another way that Christian Nationalism parallels Wicca is in where it eventually leads.

Rossman notes that as Wicca developed, it attracted a wide range of adherents with wildly different interpretations. Some were harmless romantics celebrating nature. But others ended up in dark places. The Nazis, Rossman points out, were enthusiastic proponents of the theory that Christianity had suppressed authentic Germanic paganism in a way that protected the Jews. Heinrich Himmler tasked the SS with creating a “Hexenkartothek,” an index cataloguing every witch execution as evidence of Semitic assault on Aryan women.

The ideology of paganism didn’t require antisemitism. But once the infrastructure was built, the roads led to ugly destinations.

Something similar is happening with Christian Nationalism. It’s truly baffling that some who adopted the label of nationalist are surprised by the rise of antisemitism in their movement. Since Jews almost always get classified as the “Not-Us,” nationalism has historically—nearly universally—led to antisemitism. Historically, this has nearly always been the case. We should not be surprised.

DeYoung points out, “Some of these proponents traffic openly in racist ideology, antisemitism, and Neo-Nazi sympathies. The most strident Christian Nationalism proponents on social media are often a potent combination of oafery and demagoguery.”

This turn toward hate-based extremism is not accidental. Some were already racist or antisemitic when they joined the movement. But others adopted “nationalist” as an identity without understanding what nationalism historically entails. Then, having embraced the label, they become susceptible to the intellectual currents that have always traveled with that ideology. The “red-pilling” process that brings someone to Christian Nationalism often continues, leading him or her deeper into non-Christian forms of nationalism and other movements where antisemitism, racialism, Nazism, and other types of authoritarianism flourish.

Once someone has publicly committed to an identity—defended it against critics, lost friends over it, organized his social media presence around it—he becomes psychologically resistant to abandoning it even when discovering its uglier associations. The performative theory has shaped him; he’s built a community and an identity around it. Now, to give up that identity would be to give up his sense of self.

Better Way Forward

What would it look like to affirm what’s legitimate in the Christian Nationalist impulse while rejecting its errors?

DeYoung points to Samuel Miller, an 18th-century Presbyterian pastor who advocated what he called “enlightened patriotism.” Miller believed Christianity was essential to America’s health and that Christians should work to see sound doctrine spread throughout society. But he explicitly rejected any “species of alliance between church and state” as “a calamity and a curse.”

Once someone has publicly committed to an identity, he becomes psychologically resistant to abandoning it even when discovering its uglier associations.

It wasn’t so long ago that most American Christians felt the same way as Miller. In 2007, I wrote in a conservative magazine that American Christians aren’t Muslims—we don’t want a theocracy: “More than half of American evangelicals are either Baptists or nondenominational—groups that don’t even want a centralized church government much less a central government controlled by the church.” At the time, that statement seemed true. Yet today we have some Baptists(!)—a tradition famous for supporting autonomy of the local church and religious liberty—clamoring for a “Christian prince” to tell us how to live and how we can practice our faith.

The Reformers understood the role of the state was to protect the church, not to command it.This is what distinguishes the Reformation project from traditions where nationalism is yoked with Christianity. In Russian, the Moscow Patriarchate, for example, has long functioned as a spiritual arm of imperialism, with priests blessing both tsars and tanks. Spanish National Catholicism under Franco fused ethnic identity, authoritarian politics, and the church into a single evil regime. In both cases, the church became a servant of “Christian princes” who profaned the name of Jesus.

We shouldn’t want an officially Christian nation overseen by power-hungry monarchs. We should want a nation that’s demonstrably Christian and made up of actual followers of Christ.

What might this look like practically?

It would look like celebrating America’s Christian inheritance without fabricating a history that never existed. Many founders were sincere Christians, and Christian ideas shaped the founding documents. Christianity remains essential to American flourishing. We don’t need Barton-style embellishments to tell that story.

It would mean working for Christian influence in public life without asking the state to adjudicate theological questions. DeYoung puts it well: “I do not want government to direct its citizens to the highest, heavenly good, or to order society around true religion, because I do not trust the government to determine true religion from false religion.”

It would look like defending religious liberty—including for people whose religions we believe are false—while still advocating for Christianity’s place in the public square. The First Amendment isn’t a mistake to be corrected; it’s a Christian achievement to be celebrated. The genius of disestablishment was precisely that it allowed Christianity to flourish without state patronage.

It would look like recovering Abraham Kuyper’s concept of sphere sovereignty—the recognition that God has ordained multiple institutions (family, church, state, business, education), each with its own legitimate authority. The state isn’t supreme over all of life; it’s one sphere among many. Christian Nationalism tends to fixate on capturing the state as the lever for cultural transformation.

Sphere sovereignty reminds us that a faithful family, a healthy congregation, or a justly run business is doing kingdom work that no government program can replicate or replace. We can build institutions that embody Christian conviction without waiting for political power to impose it. This is slower work than seizing the state, of course, but it’s more durable and more faithful.

Finally, it would look like being patriots rather than nationalists. We can love our country, work for its good, and serve our neighbors through political engagement without making the nation an idol or treating our particular national identity as ultimate.

Danger of Performative Nationalism

The deepest lesson from the Wicca comparison is that false ideas, once believed and acted on, create realities that take on lives of their own.

Murray’s theory about medieval witchcraft was wrong. But because people believed it, they created an actual religion based on her imagination. Now there really are covens and priestesses and rituals, and some practitioners sincerely believe they’re practicing an ancient faith.

We don’t want an officially Christian nation. We want a nation that’s demonstrably Christian.

Similarly, the Christian Nationalist vision of America’s past is largely invented. They claim to be recovering something that never existed. But because people believe it, they’re creating a movement based on an invention that has its own heroes; its own historical narrative; and, increasingly, its own dark fellow travelers. We’re already seeing the movement become less “Christian” as it becomes more nationalistic.

If you’re a Christian attracted to this movement, you should ask yourself some hard questions. Do you want to build on a foundation of historical fiction? Are you comfortable with the company this ideology keeps? Do you want to align with a movement that was birthed in Marxism and antisemitism? Is “nationalist” really the adjective you want modifying your faith?

There’s a better way. It involves loving America without worshiping it, serving Christ without confusing his kingdom with any nation-state, and building for the long term rather than grasping for power in the moment. It’s less seductive than the Christian Nationalist alternative. But it has the significant advantage of being true, sustainable, and genuinely Christian.