www.thecollector.com

How the Astor Family Sold Fur and Became the Kings of New York

The Astors didn’t just waltz into wealth—they built it from the ground up, leveraging everything from fur pelts to Manhattan real estate to carve out their place as American royalty. Starting with a savvy German immigrant who knew exactly how to turn a profit in a growing nation, the Astors transformed their fortune with each generation, shaping New York’s social elite. Long before the Vanderbilts or the Rockefellers came onto the scene, the Astors were already kings of the city—unrivaled in influence, status, and, of course, scandal. Here’s how they rose from wilderness traders to high-society titans.

Astors: Roots and Founders

Persecution of the Huguenots, The Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, by François Dubois, c. 1572-1584. Source: The Cantonal Museum of Fine Arts, Lausanne, Switzerland

Before the Astors were Manhattan’s ruling elite, they were modest French Huguenots who had fled to Germany in search of religious freedom and away from terrible persecution. In those days, they were about as far from respectable monied society as could be. John Jacob Astor’s father, a butcher by trade, kept the family afloat on blue-collar hard labor. John Jacob had bigger dreams, though he did assist his father with the family business. He’d been born in Walldorf, Germany, in 1763, a place worlds away from the glittering New York empire he would one day build. He knew, early on, that Europe was no land of opportunity for a man like him.

So, in 1784, at the tender age of 20, Astor boarded a ship bound for America, where he wasted no time figuring out how to make a fortune. From wisdom gained via speaking to a fellow passenger, he quickly set his sights on the beaver fur trade—an industry that was, quite literally, “in fashion.” The fur of the American beaver was all the rage in Europe, thanks to its durability and soft texture, which made it perfect for the top hats gracing the heads of the era’s most fashion-forward gentlemen. It was a lucrative business, but an unregulated one, and Astor understood that if he wanted to make a name for himself, he’d have to be tougher than the most ruthless competition.

Trappers in the Wilderness, 1897. Source: Picryl

Astor quickly got his hands dirty, cutting deals with Indigenous trappers who were skilled at procuring the prized pelts. However, let’s be clear: Astor’s business strategy wasn’t about fair trade or ethical practices. He profited by barely compensating Native hunters a pittance for their work, securing valuable furs for prices that absolutely took advantage of the skilled labor he relied on to secure the product. As demand skyrocketed on both sides of the Atlantic, his income climbed accordingly.

By the early 1800s, Astor’s monopoly over the fur trade had turned him into one of America’s richest men. However, Astor wasn’t one to rest on his laurels: once he’d cornered the fur market, he moved on to real estate, snapping up land in what was then the wild fringes of New York City. It is safe to say that if a deal was cutthroat, underhanded, or downright exploitative, Astor’s name was attached. In fact, at the end of his life, he said his only regret was not gobbling up more land for his real estate portfolio.

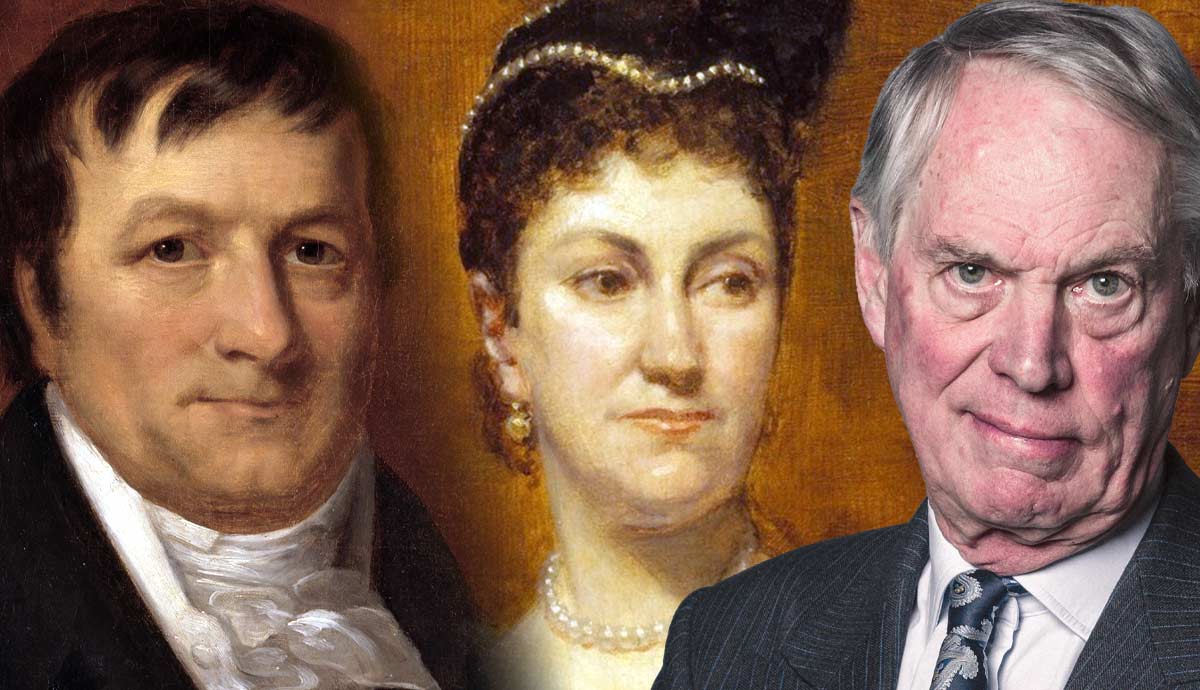

John Jacob Astor, by John Wesley Jarvis, 1825. Source: National Portrait Gallery, Washington

Astor wasn’t entirely alone in his ascent. There was another fighter in the ring with him, one just as wily and forward-thinking. In 1785, he married born New Yorker Sarah Todd, a resourceful lady who would prove herself a formidable business partner and advisor. They met when he rented a room in the Manhattan boarding house that Sarah managed with her widowed mother.

Though John Jacob was later known to remark that he wanted to wed Sarah “because she was so pretty,” it is worth noting she also brought a $300 dowry (about $10,000 in today’s money)—likely as attractive to the ambitious young immigrant as her beauty. That dowry was their start, allowing them to open a small business selling musical instruments. But it wasn’t long before they shifted focus to the more rapidly profitable fur trade, and Sarah quickly became more than just a traditional helpmeet.

With a sharp eye for fur quality, Sarah managed the business whenever her husband was away on buying expeditions. She supervised the labor-intensive and rather noxious task of processing pelts, negotiated sales, and kept the whole operation afloat—all while raising their eight children, five of whom lived to adulthood. So adept was she at managing the Astor empire that, according to legend, she even faced accusations of witchcraft. Her real crime was only that she was a woman with a knack for business.

Real Estate and the Legacy of Land

Astor House, 1893. Source: Picryl

If there is one thing to know about the Astors, it is that they didn’t just build wealth, they acquired it by buying, holding, and squeezing every last drop of worth out of New York City’s real estate market. Unlike other city landowners, who’d occasionally show mercy to their tenants or invest in building upkeep, John Jacob Astor pioneered what could only be described as “the art of planned neglect.” His real estate strategy was less about developing beautiful properties to stand the test of time and more about padding his empire by any means necessary.

Caricature from the 1837 panic, The Times, 1837. Source: Library of Congress

Evidence exists of him leasing land to sublandlords on contracts that sounded like a sweet deal—until you read the fine print. Astor would lease his plots for new construction under a clause stating that, after a mere 20 years, all buildings on the land would revert back to the Astor family.

As you might imagine, when you’re only going to “own” a building for two decades, there’s little motivation to keep it in top shape. These sublandlords knew they would be handing back the keys to the Astors sooner rather than later, so there was no incentive to fix the leaky roof or update the sagging floors. As a result, many Astor-owned properties became dilapidated eyesores well before their time—an early example of strategic “deferred maintenance.”

Then there was the great Panic of 1837, which nearly obliterated New York’s real estate market. Property values crashed harder than a 1929 ticker tape, and families citywide found themselves unable to stay current with their mortgage payments. The state of New York even had to step in with a grace period, giving homeowners an extra year to catch up before foreclosure or eviction. For most people, it was a time of desperation and constant stress. For John Jacob Astor, it was just another chance to get what he wanted for discount prices.

John Jacob Astor, 1896. Source: Picryl

While other higher-ups were frantically selling off assets to stay solvent, Astor calmly snatched up prime Manhattan parcels for almost nothing. In 1837 alone, he spent a whopping $224,000 on land—a sum that would equal more than five million dollars today—and he did it with the patient, calculating confidence of a man who knew exactly what he was doing.

When interest rates shot up to 7%, Astor was the master of other peoples’ mortgages that were ticking fiscal time bombs. Those who couldn’t keep up with the payments saw their properties foreclosed, their American dreams slipping directly into Astor’s overstuffed back pocket. Call it coldblooded or call it cunning, but John Jacob Astor never missed an opportunity to turn someone else’s worst moments into his underpriced victory.

All that money and success did not make the family run smoothly as it continued to expand. Take the legendary feud between Caroline Astor—who, despite an unhappy marriage to an uninterested man, insisted she was the Mrs. Astor—and her nephew, who wanted his wife, Mary, to carry the vaunted title. When Caroline refused to share the mantle of “Mrs. Astor,” and the esteem that went with it, her nephew decided to really stick it to her. He built a luxurious hotel right next to Caroline’s grand mansion, something that granted anyone with enough money the one thing Caroline liked to be the gatekeeper of access.

Caroline couldn’t stand this, bought and moved the family to another sprawling property, and built her own hotel right beside William and Mary’s to be in perpetual competition. The hotels stood shoulder-to-shoulder like stubborn siblings, each vying for dominance in New York’s high society. It is a tale of egos, money, and enough petty competition to make a reality TV producer salivate.

The Women of the Astor Family

Caroline Astor, by Carolus-Duran, 1890. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Astor women, both those born into the wealth and those who married in, were busy shaping society, surviving tragedies, and, on occasion, causing a scandal or two. Each generation seemed to produce at least one Astor woman who made her own kind of history, whether it was through philanthropy, societal reinvention, or a headline-grabbing escape.

Take Madeleine Astor, for instance. At just 19 years old, Madeleine was the young bride of John Jacob Astor IV (the great-grandson of the founder of the New York dynasty, John Jacob), who, at 47, was several decades her senior. The two were honeymooning overseas when she became pregnant. Discovering this, the newlyweds booked passage back to New York on the luxury liner, the Titanic.

What ensued next was a shocking tragedy: while Madeleine made it into a lifeboat and survived, Mr. Astor did not. Left widowed before she’d even reached her 20s, Madeleine and, later, her and the late John Jacob IV’s son, became somewhat synonymous with the sinking. Madeleine and her boy were handed a fortune but with a rather significant caveat—Astor family rules dictated she’d lose her inheritance if she remarried.

Resourceful and a romantic, she eventually did marry again, turning down a life of well-paid mourning in favor of love, even if it meant losing her claim to the family fortune. Madeleine became, in short, a survivor in every sense.

RMS Titanic, April 10, 1912. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Then there was Caroline Astor, the grand dame who essentially invented New York high society. Known simply as “the Mrs. Astor,” Caroline held court in her mansion and famously conceptualized a list of New York’s 400 most “acceptable” people—the magical number, she said, that could fit into her ballroom at one time.

To make her list was to be granted entry into the elite echelons of New York society. Caroline was known to snub even the wealthiest newcomers if she felt they lacked pedigree. In a world where family lineage was everything, she was the ultimate madam judge, standing firmly on the social ladder that every up-and-coming family aspired to climb.

Madeleine Force Astor, 1910. Source: Picryl

Magdalena Astor, on the other hand, took her own path and wasn’t about to let any man—or empire—run roughshod over her life. She married the Governor of the Danish West Indies at 18 years old, a man of considerable status and power, only to decide that the life of a people-pleasing diplomatic spouse was not her cup of tea.

After a few years and two buried children, she simply packed her bags and left him. In an era when divorce was utterly scandalous, Magdalena walked away from a high-ranking position and sought after title in pursuit of her own freedom. She was a woman who would not settle, even if it meant defying social norms. She later married again to a lawyer/doctor who became a practicing clergyman.

View of St. Thomas harbor in Charlotte Amalie, Danish West Indies, by Fritz Melbye, 1851. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Brooke Astor was perhaps the most beloved of the Astor women in recent memory. She married into the family and laid her husband to rest after just five years of matrimony. Brooke gave away millions of dollars over her lifetime, supporting libraries, cultural institutions, and educational programs across New York City. She became known as the “first lady of philanthropy,” embodying the kind of grace and generosity that helped shape the perception of old money—but with a warmth and forthrightness that made her truly adored.

Tragically, in her final years, Brooke suffered criminal mistreatment at the hands of her son, Anthony Marshall, who attempted to seize control of her estate as her health declined. In a story that became tabloid fodder, the beloved philanthropist was thrust into the spotlight once more, as New Yorkers rallied around her in court to ensure her son couldn’t drain her assets before her death.

He had, apparently, been keeping his mother in squalor and refused to even install railings on her bed, though she’d fallen from it multiple times. Her son was eventually convicted of grand larceny, and Brooke’s memory lives on as a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Her motto, adopted from a theater production, also continues to inspire; “Money is like manure; it’s not worth a thing unless it’s spread around.”

In a world dominated by ruthless men, the Astor women carved out their own power, on their own terms. Sarah Todd would certainly be proud.

English Connections and Aristocratic Ties

Astor Wing at Hever Castle, by Jayembee69. Source: Flickr

William Waldorf Astor, the aforementioned builder of a hotel to spite his aunt and famously disgruntled by his treatment in New York society, led the charge overseas. Once in England, William Waldorf was determined to make a name for himself among the nobility. His line of thinking went something like this: what better way to cement one’s status than by acquiring a piece of Tudor history? He achieved this via the purchase of Hever Castle, the childhood home of Anne Boleyn, the queen who lost her head and birthed the child that would become England’s Gloriana.

William poured his substantial wealth into restoring the castle to its former glory, and, not one to do things halfway, he went so far as to build an entire mock Tudor village nearby. The English aristocracy might have initially scoffed at his colonial manners, but William was intent on proving he had the resources—and the audacity—to fit right in. With his American fortune, he soon turned Hever Castle into an aristocratic playground, inviting high society to experience Tudor opulence with all the comforts of modern wealth.

During the tense years leading up to World War II, the English branch of the family found themselves in a much darker chapter of history. Members of the Astor clan were reportedly present at the infamous Cliveden Set gatherings—a group of influential figures who believed, to the horror of many, that Britain should pursue peace with Hitler’s regime. This circle of appeasement, meeting at the Astors’ own Cliveden House, cast a long, Nazi-shaped shadow over the family’s legacy. Many in the know still debate just how involved they were in encouraging capitulation, the very association left notable asterisks behind the Astor name.

Clivedon House, photo by Daderot, 2005. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Amid these complicated connections to British high society and political intrigue, one Astor woman was determined to make her own name in politics—Nancy Astor. Born an American but transplanted to England by her marriage to Waldorf Astor (William’s son), Nancy became the first woman to blaze her way to taking a seat in the British Parliament.

With her inability to back down under pressure and fiery personality, she defied expectations. Famed for locking horns with Winston Churchill and speaking her mind on issues from women’s rights to prohibition, Nancy’s political career opened a door many didn’t know was there. Her ascent from Virginia society girl to a political powerhouse in Parliament was nothing short of groundbreaking, further entrenching the Astor name in the annals history.

The Astors carved out a legacy in England as audacious as their American one. They had, perhaps, traded Manhattan for the English countryside but their flair for the dramatic remained very much intact.

Modern Astors and Legacy

Official portrait of Lord Astor of Hever, 2018. Source: UK Parliament

Today, their legacy stretches across continents. David Astor, son of Nancy Astor, was a prominent figure in the media and social justice arenas. As the longtime editor of The Observer, he used his platform to champion progressive causes, including anti-apartheid activism. His work earned him a reputation as one of Britain’s most respected journalists, committed to both truth and change. He was to the Astors what Anderson Cooper is to the Vanderbilts.

The Astor influence remains in British politics as well. William Astor, 4th Viscount Astor, holds a seat in the House of Lords, representing the modern face of the family in governance. Through his marriage, he also became the stepfather of Samantha Cameron, wife of Prime Minister David Cameron. Similarly, another John Jacob Astor, third Baron Astor of Hever, served in the House of Lords from 1986 until his retirement in 2022.

The Astors remain well-connected to the British aristocracy. William Waldorf Astor’s great-great-granddaughter, Rose Astor, married Hugh van Cutsem, a close friend of Prince William. Their daughter, Grace, became an unexpected media darling as the adorable but “grumpy” bridesmaid at the globally watched royal wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton in 2011.

Rose, who professionally goes by her maiden name to avoid confusion, co-founded a posh London club for mothers in Kensington with amenities that cater to both kids and adults—from wood-fired pizza to child-friendly yoga classes. Though she left the venture after a few years, Rose later joined Soho Farmhouse, curating memberships for one of the UK’s most exclusive clubs. She is, perhaps, the modern iteration of Caroline Astor, gaining wealth and recognition by gatekeeping elite spaces for women.

Harry Lopes and Wife. Source: Pinterest

Another descendant, Harry Lopes, married adjacent to British royalty. He wed Laura Parker-Bowles, Queen Camilla’s daughter, further reinforcing the Astor connection to British aristocracy.

There is also Prince Serge Obolensky, an Astor descendant who connects the family to Russian nobility. Serge was born in London but carried the legacy of both the Obolensky family of Russian princes and his Astor lineage. Through him, the Astors can now trace a line back to the ancient Rurikid rulers of Kyivan Rus’, linking them to an empire that predated the infamous reign of the Romanovs.

The Astor legacy is a unique blend of old-world aristocracy and modern-day influence—a family whose mark on history spans continents, centuries, and even ideologies. The Astors may no longer rule New York’s land or high society, but their presence is felt in places they couldn’t have imagined when their story first began in the fur trading business.