www.thecollector.com

The Hidden Side of Abraham Lincoln

Ask the average American what they know about former president Abraham Lincoln, and answers will likely relate somehow to the American Civil War and Lincoln’s role in the abolition of slavery. Lincoln is largely credited with freeing slaves with his 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. However, a closer look at Lincoln’s words and actions brings up questions. Was Lincoln truly the humanitarian that history credits him with being?

Anti-Slavery Crusader?

Young Lincoln spoke out against slavery—but to what extent? Source: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons

There is little doubt that Abraham Lincoln was against the idea of slavery. In 1841, he saw a group of slaves shackled in irons on a riverboat trip, a sight which bothered him and stuck with him. He spoke of the occasion and its impact on him in a letter to a friend in 1855, in which he stated his opposition to the extension of slavery. He continued to hold this view in his early political career, even describing himself as being anti-slavery. However, he did not campaign for immediate emancipation. In a speech given in Peoria, Illinois, in 1854, he came close to defending southern slave owners, stating that he had “no prejudice against the Southern people” and believed that they were “just what we would be in their situation.”

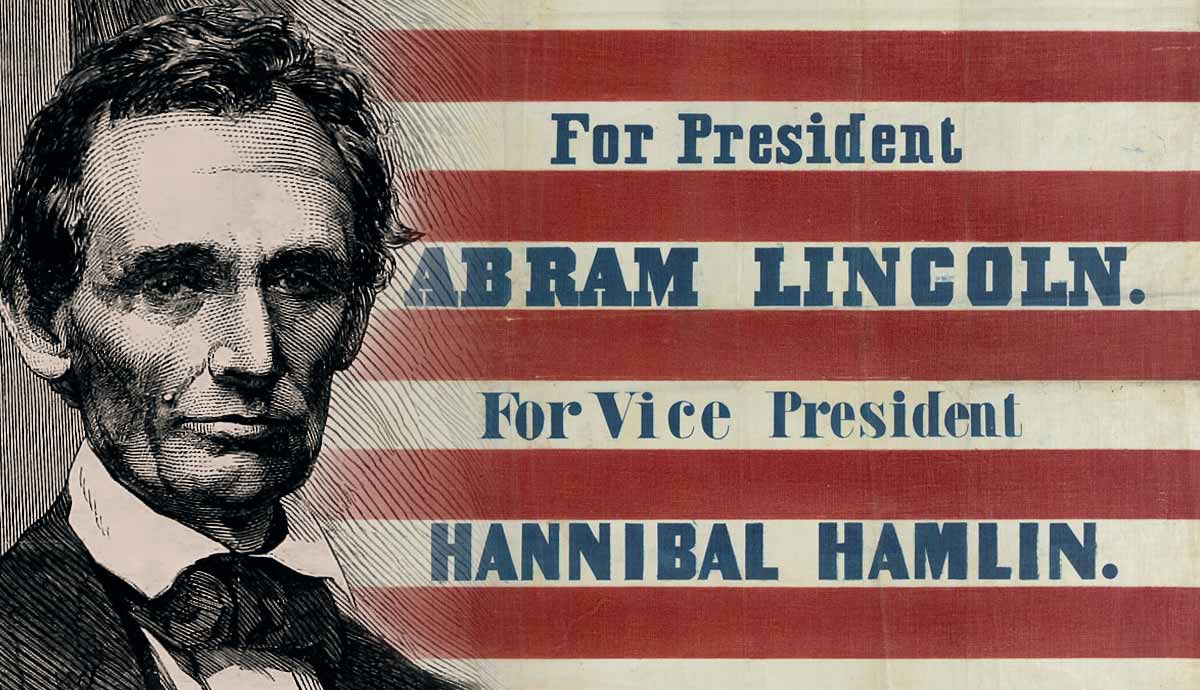

This pro-Lincoln banner was flown leading up to the 1860 presidential election despite the misspelling of the candidate’s first name. Source: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons

Still, Lincoln’s anti-slavery views made an impact on his political career. When he ran for president in 1860, his opponents, notably Southern Democrats, utilized his views as scare tactics. One Georgia pro-secessionist spread the rumor that Lincoln planned to force the intermarriage of Blacks and whites and that within ten years, white children would be “slaves of Negroes.”

The Charleston Mercury and other newspapers published scathing critiques and cartoons of Lincoln in crude depictions with African Americans. Even though Southerners feared Lincoln’s anti-slavery rhetoric, his statements and efforts regarding the cause were not enough for many abolitionists. Many viewed him as appealing to a “moderate” anti-slavery view rather than a full believer in the cause. Lincoln seemed to be focusing more on preventing the spread of slavery rather than doing away with it entirely. His speech on February 27, 1860, in New York, referred to as the Cooper Union Address, cemented this idea in the heads of many abolitionists. In his address, Lincoln said, “Wrong as we think slavery is, we can yet afford to let it alone where it is…” and referred to using votes to stop its spread to current “free” states.

Several prominent abolitionists spoke out against Lincoln and even went so far as to abstain from voting, but the majority of abolitionists who did vote in 1860 chose the Republican. Lincoln would not even be placed on the ballot in many Southern states but still carried the election. When he became president, he chose cabinet members who opposed slavery.

Was Lincoln an Abolitionist?

This optimistic cartoon by Thomas Nast spoke to hope in regard to abolition after the Civil War. Source: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons

In 1858, Lincoln stated, “I have always hated slavery, I think as much as any abolitionist.” Nevertheless, Lincoln was no abolitionist. Though political opponents used his anti-slavery views to appeal to their supporters and inspire fear, Lincoln had no plans to free America’s slaves as he became president.

However, some, such as Frederick Douglass, had hope that Lincoln’s views on slavery would help pave the way for true abolition in the future. When he was elected, Lincoln’s first priority was to preserve the Union, a priority that continued throughout the Civil War. As the war progressed through the early 1860s, Lincoln was forced to confront the issue of slavery. After all, it was the main factor for the division of the states to begin with.

A print featuring Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation. Source: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons

In September 1862, Lincoln issued a threat to his Southern counterparts. He promised that if the war continued, on the first day of January 1863, he would issue a decree freeing slaves in the rebellious states. His warning was not heeded, and in January, the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, forever branding the president the “Great Emancipator.”

However, it is important to note that the proclamation only outlawed slavery in the states that were in rebellion or part of the Confederacy. Areas that were occupied by Union forces, regardless of location, were exempt from the proclamation. This exemption covered territory in many slaveholding states, including South Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, and Mississippi. Though slavery was essentially defunct in the North at that time, it wasn’t nonexistent, with almost two thousand slaves still on record. Lincoln made no moves to make abolition a blanket policy for the whole country.

Believer in Equality?

A Harper’s Weekly illustration shows Lincoln attacking slavery, represented by a tree. Source: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons

Though Lincoln touted equality in his Gettysburg Address in 1864, he seemed to have some hesitation about whether or not whites and Blacks could live equally in America. In his 1854 Peoria speech, he suggested that his “first impulse” if the slaves were freed was to return them to Liberia in Africa. Realizing that this idea was impractical, he didn’t give up the idea of moving freed slaves elsewhere.

In 1861, he made a trip to Panama to visit the land of a Philadelphia man named Ambrose Thompson, who had volunteered his jungle holdings as a refuge for freed slaves. He went on to support Congressional bills that would provide money to relocate freedmen to Haiti, Liberia, or “such other country beyond the limits of the United States as the president may determine.” The preliminary version of the Emancipation Proclamation included language about the effort to relocate freed slaves “elsewhere.”

What Was Lincoln’s Indigenous Policy Like?

Parker Peirce’s rendition of the mass hanging of 38 Dakota men in 1862. Source: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons

Lincoln’s views on the Indigenous people of the United States aren’t in the spotlight as frequently as his efforts in relation to African Americans. His ideas in this regard mirrored those that were generally accepted by the US at the time. Indigenous tribes were seen as a threat to American settlers and the ability of the United States to grow and prosper.

Growing up on the frontier, Lincoln’s interactions with Native Americans were often negative and helped develop his racial attitudes. In addition, Lincoln voluntarily served as a militiaman against Indigenous forces during the Black Hawk War, although he did not actually see any combat. As president, Lincoln was directly responsible for several actions that continued to sour US-Indigenous relations, including allowing the deaths of 38 Dakota warriors in 1862 in the largest mass execution in US history. He issued the Emancipation Proclamation only five days later.

Was He a Humanitarian in Other Ways?

This photo of an unidentified, emaciated prisoner from Belle Isle Confederate Prison illustrates some of the horrors Civil War prisoners were subjected to. Source: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons

Though Lincoln may not have lived up to the title of abolitionist or have been known for working toward peace with Indigenous tribes, he did prove himself to be a humanitarian in other ways. The Geneva Convention, a global pact in which several nations pledged to avoid certain actions that threatened humanity in wartime, wasn’t signed until 1864, when the Civil War was concluding. Before that, Lincoln had made efforts to prevent the Union Army from acting cruelly, even in a period as disastrous as the American Civil War.

In 1862, Lincoln consulted legal scholar Francis Lieber of Columbia College for help forming humanitarian guidelines for the treatment of Confederate soldiers. Approved by Lincoln in April of 1863, Lieber’s “Instructions for the Government of Armies of the United States in the Field,” known as the Lieber Code, called for the humane treatment of Confederate forces after loss or capture. This was the first time that limits existed on certain military actions and underlined the importance of humanizing elements of warfare.

Though Lieber’s, and in turn, Lincoln’s recommendations were not always followed to the letter, such as in the case of Sherman’s March to the Sea (the code recommends avoiding the looting and destruction of civilian property), the broad recognition was that Confederate soldiers were still Americans and should be treated as such. Lincoln also outlawed the use of torture and poison in the Union army’s tactics.

Lincoln featured in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, October 20, 1860. Source: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper / Wikimedia Commons

While in reality, Abraham Lincoln may not completely live up to the title of “Great Emancipator,” he does deserve some credit for his role as a leader during the most divisive time in America. He proved himself willing to listen to the voices of all Americans, a quality often so lacking but much desired in elected officials. Lincoln’s legacy may be exaggerated at times, but it is enduring. He may not have been the abolitionist he is sometimes championed as, but his anti-slavery viewpoint and efforts to preserve the Union undoubtedly played an important role in advancing the United States towards a more progressive and fair future.