reactormag.com

Joyfully Revisiting Swordheart by T. Kingfisher

Books

book review

Joyfully Revisiting Swordheart by T. Kingfisher

An unabashed love letter to a modern fantasy classic.

By Liz Bourke

|

Published on April 14, 2025

Comment

0

Share New

Share

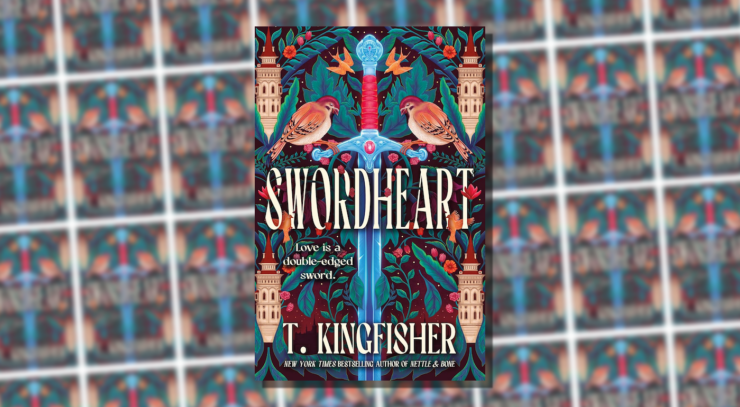

Swordheart was first published in 2018 by Ursula Vernon writing as T. Kingfisher. I adored it then. I adore it now. And I have the challenge of reviewing a novel that exemplifies what is best in Kingfisher’s work: the generosity of spirit, the eye for the ridiculous, the compassion and the pragmatism, the humour and the weirdness, all wrapped up in the self-contained frame of Kingfisher’s (re)invention of a genre I can only call “sword and sorcery romance.”

Halla of Rutger’s Howe is a woman approaching her middle years. Widowed young (and not exactly displeased to be so), she’s spent the years since her widowhood as housekeeper and general dogsbody for her great-uncle by marriage, Silas. Silas, a collector of peculiarities and a man of property, is dead when the novel opens. He’s left all his property to Halla. Bad news for Halla: Her in-laws thought the property would come to them. Worse news for Halla: Her in-laws are terrible people, who fully intend to force her to marry Cousin Alver, and shut her up to bear his children, in order to keep the property in the family. Alver has clammy hands, no personality, and takes direction from his mother, the deeply unpleasant Malva. Halla has no desire to be subject to such a future. She doesn’t particularly want to die, but living under these conditions would be intolerable. So, locked in her room and kept there by the in-laws, she’s looking for a way to kill herself. But when she draws the (long, awkward) sword that’s been hanging on the wall for as long as she’s lived there, a man appears in a flash of blue light.

Sarkis was a mercenary leader when he was alive. He’s been bound to, and in, the sword for centuries, compelled to protect its wielder, only able to experience the world when the blade is drawn, held in silver dreams in between. Unable to die: His binding to the sword heals his wounds, even mortal ones, for he is already dead. Long years have passed since his sword was last drawn. He’s hardly expecting to emerge in front of a woman showing rather more breast than he’d normally see, who immediately starts babbling—asking him more questions than he knows what to do with. She needs defending from her family. He can do that; he’s good at violence. She needs legal assistance to claim her inheritance? That’s a bit beyond his skillset.

After a dramatic escape in which they flee Rutger’s Howe via the graveyard gate, they set out on an uncomfortable roadtrip to the closest big city to petition for help at the Temple of the White Rat. Other gods have holy paladins, fight demons, or burn suspected witches (the very unpleasant priests of the Hanged Mother, also known as the Motherhood, like to do this latter); the White Rat solves problems, and brings holy lawyers to the fight. Along the road, both Sarkis and Halla find themselves attracted to the other, and discover that they appreciate each other’s skills and sense of humour; neither believe that the other could possibly find them attractive in turn, and even if their interest was returned, it’d be bad form to pressure the other person when they’re rather relying on each other for certain basic needs and dignities.

Buy the Book

Swordheart

T. Kingfisher

Buy Book

Swordheart

T. Kingfisher

Buy this book from:

AmazonBarnes and NobleiBooksIndieBoundTarget

Swordheart is set in the same world as Kingfisher’s prior Clocktaur Wars duology and her subsequent “Saint of Steel” series of novels (Paladin’s Grace and sequels, which are romances with rather more severed heads than your average romance novel). The Temple of the White Rat is a presence in all these novels, to greater or lesser degree. Halla receives assistance from Bishop Beartongue, who’d like to be able to help Sarkis too (Beartongue and Halla’s conversation about how you’d fake Sarkis being bound to the sword—the appearance and disappearance of a man in a flash of light—is a highlight of the novel, and emblematic of Halla’s deeply interested and curious approach to the world), but the most she can do is make sure that neither Sarkis nor Halla feel coerced by the other.

Nonbinary priest Zale, who’s a lawyer with the appropriate skills, is the primary means of assistance offered by the White Rat. The legal case itself is straightforward, once Zale gets to work—except that Halla’s relatives-by-marriage are unwilling to take their defeat lying down, and Halla’s attempt to give Sarkis to himself (angrily, immediately after learning a truth about his history as a living man) backfires into additional complications. Kingfisher keeps the pace and tension mounting with unexpected turns and reversals, right to the very last page.

I’ve described sword-and-sorcery before as the “fantasy of encounter,” in which people meet with fantastic incidents in the course of their lives and work. That’s part of why I see Swordheart—and indeed, the “Saint of Steel” books—as a quintessentially sword-and-sorcery sort of romance: Halla’s quest is, at root, about a very understandable problem. She just meets with a lot of strangeness on the way, usually with generosity of spirit and kindness, frequently with many questions, and often with a deep pragmatism and sense of humour. Sarkis, the man bound to a sword, belongs to the classics of sword-and-sorcery, and mutters about “decadent civilisation” with the best of them. Their roadtrip together recalls in part the atmosphere of Robert E. Howard or Fritz Leiber, in part Jennifer Roberson’s Tiger and Del or Mercedes Lackey’s Tarma and Kethry stories, but with Kingfisher’s trademark sense of the ridiculous and with updated sensibilities. Such as, for example, when Halla and Zale convince Sarkis to participate in an experiment to determine whether his bodily fluids remain behind when he de-materialises into the sword.

You can call Swordheart a fantasy romance, and indeed it is. But in its attention to the weird and the ordinary, the unsettling and the quotidian, to travel and encountering strangeness in the course of what would otherwise be normal events, sword-and-sorcery is intrinsic to its makeup. And to its atmosphere.

Among all the humour and banter, adventure and entertainment, this is a novel with depth. Sarkis is haunted, in Kingfisher’s understated emotional register, by old grief and terrible suffering. Halla is worn through with years of responsibility, penned up by poverty and respectability, painfully aware of her vulnerability. Swordheart is a novel that starts with a man who can’t die but wants to, meeting a woman who can die and doesn’t want to, but is nonetheless trying to in order to escape an intolerable situation. They are both trapped. With each other, eventually, they find support, mutual respect, understanding, and greater freedom. They respect each other’s autonomy so much in part because they’ve had the experience of being trapped themselves.

They also misunderstand each other and make mistakes. Some of which involve stabbing. The course of true love never did run smooth, did it?

I love this novel to pieces. So many individual parts of it are wonderful, from Halla learning an ox’s name to Zale shifting into full-on dramatic lawyerly performance when, as a travelling companion, they’d been nerdy and slightly overwhelmed in the face of stabbing and hills that move. But Swordheart is more than the sum of its parts: It gathers up all its incidents and transmutes them into a greater whole. If you haven’t read it yet, then today’s your lucky day: You get to read it for the first time.

And if you’re anything like me, several more times after that.[end-mark]

Swordheart is published by Bramble.

The post Joyfully Revisiting <i>Swordheart</i> by T. Kingfisher appeared first on Reactor.