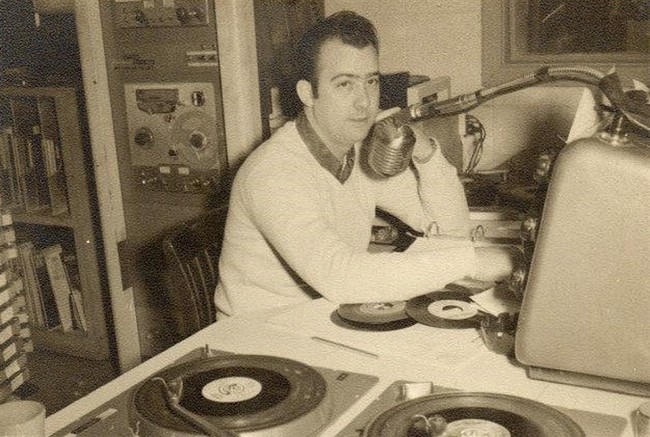

When I was but a fledgling general assignment reporter in west-central Wisconsin 30-odd years ago, I left college with the belief that it was critical to share opposing views in my stories. Of course, I worked in radio—face made for radio, voice made for print!—which made equal time a challenging goal to achieve, especially when sharing a complex topic.

Advertisement

On the FM side of the dial, I had 15 seconds; on the AM side, 30 to 60 seconds, while our news director made us write three versions so they always sounded different.

I took pride in my results, particularly when the topic was hot, such as when plans for the Highway 53 bypass around Eau Claire were announced. I felt I earned a badge of respect when a DOT official complimented me on simplifying and concisely explaining the disputes. That's where I started using analogies; if you've ever rolled your eyes at one, blame radio.

Shortly before Manney was set loose on the air, the Fairness Doctrine was repealed in 1987. If you've never heard of it:

U.S. communications policy (1949–87) formulated by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that required licensed radio and television broadcasters to present fair and balanced coverage of controversial issues of interest to their communities.

The origins of the fairness doctrine lie in the Radio Act (1927), which limited radio broadcasting to licensed broadcasters and mandated that licensees serve the public interest. The Federal Communications Act (1934) supplanted the Radio Act and created the FCC, the chief regulatory body governing the U.S. airwaves, with a mission to “encourage the larger and more effective use of radio in the public interest.”

While the fairness doctrine originated in the Radio Act and was subsequently codified in the Communications Act, the two are not identical. For example, the iconic standard for broadcasters to give “equal time” to political candidates is rooted in the Communications Act, not explicitly part of the fairness doctrine.

Advertisement

After a few decades, we might be seeing federal regulators reaching for their stopwatches again.

The Federal Communications Commission warned broadcasters this week that talk shows discussing political candidates must provide equal time to both sides, especially with the 2026 election cycle about to go nuclear. FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr framed the reminder as enforcement of existing laws rather than a policy shift.

I'm trying to think of another instance where enforcing existing laws was implemented, but I can't put my finger on it.

What the FCC Is Saying Out Loud

The equal time law was already on the books when the Communications Act of 1934 was passed. If public airwaves offered time to legally qualified candidates, broadcasters had to provide comparable opportunities for the other side to make their point.

Historically, the law applied to paid appearances, interviews, and specific scripted programming, with exemptions for bona fide news coverage.

Carr emphasized that opinion programming doesn't receive blanket immunity; when any show crosses the line from commentary to candidate promotion, station owners are legally responsible. The FCC's enforcement landed clearly enough to send compliance officers scrambling.

That clarity carried consequences well beyond campaign ads.

Advertisement

Why Talk Radio Cares Deeply

Way before the interwebs made our world much smaller, talk radio and cable commentary built on momentum, with hosts responding to news live and taking unscheduled guests, allowing arguments to organically grow. That rhythm disrupted equal time, forcing stations to plan counterprogramming, track minutes, and anticipate complaints.

The stations facing the heaviest burden were the local stations. Large networks have the infrastructure to absorb compliance costs and legal reviews, but a small AM radio station—operating on razor-thin margins— had no chance. Enforcing equal time quietly favored scale, lawyers, and corporate insulation.

Long before any microphone turned on, that imbalance reshaped who would speak.

The Fairness Doctrine Shadow

In 1987, the Fairness Doctrine officially died when federal regulators concluded that it chilled speech rather than enhancing debate. Like water following the path of least resistance as it moved downhill, broadcasters avoided controversial topics altogether rather than risk enforcement. The result? content flattened like pancakes, leading to narrowing viewpoints.

On paper, equal time rules are different, but the effect mirrors the doctrine's legacy. Candor is replaced by caution whenever regulators oversee political balance. The efforts were led by hosts who self-edited, and producers canceled segments. Stations opted for silence over scrutiny.

Advertisement

No rule needs revival language to revive old instincts.

Names, Roles, and Power Lines

President Donald Trump dominates any political conversation; Brendan Carr, the FCC Commissioner, wields direct influence over regulatory interpretation; station owners bear liability; hosts carry risk without control; and candidates gain leverage simply by filing paperwork and demanding airtime parity.

Power flows downhill. But speech adapts. No single actor designed that outcome; bureaucracy tends to produce ambiguity while disguising intent.

A Simple Sounding Rule

In theory, equal time sounds fair: two clocks, two sides, and a balanced outcome.

As Mike Tyson famously said, strategy and plans sound great until you're punched in the face.

Reality resists that simplicity because political relevance varies daily while news cycles surge and public interest in specific figures spikes, forcing symmetrical airtime that assumes symmetrical demand, credibility, and urgency.

Public conversation, along with radio, never worked that way.

Where the Stopwatch Ends

In the golden days of talk radio, hosts never timed callers because conversation dies under measurement; arguments require room to breathe, surprise, and naturally end. Once that clock enters the room, voices shorten and edges dull.

Federal regulators claim restraint, while history suggests gravity. When the stopwatch is started, stations feel the ticking even when enforcement remains rare. The silence quietly creeps in, and, without orders, speech adjusts.

Advertisement

At the end of the day, the smelly microphone remains on the same desk, yet the room feels smaller, with longer stretches of silence, and nobody can explain why the conversation changed.

Everybody sensed the change, even when nobody admits feeling it.

Smart regulatory debates rarely arrive gift-wrapped. They demand patience, context, and historical memory. PJ Media VIP members keep those conversations alive without timers or filters.