www.historyisnowmagazine.com

The History of the Crossbow: The Rise, Reign and Resilience of the Crossbow

In the dense stillness of the jungle, a modern soldier crouches beneath the canopy, his weapon of choice silent but deadly. It's not a suppressed firearm or high-tech drone, but a crossbow. Though often considered a relic of medieval warfare, this weapon, which once helped shape the course of empires, continues to whisper through the shadows of modern conflict.The crossbow's story stretches across centuries and continents, from its earliest appearance in ancient battlefields, through its fearsome medieval dominance, to its near extinction in the face of gunpowder and finally, to a surprising modern rebirth in specialist military operations. This is the tale of a weapon designed for precision, power, and quiet lethality.Terry Bailey explains.

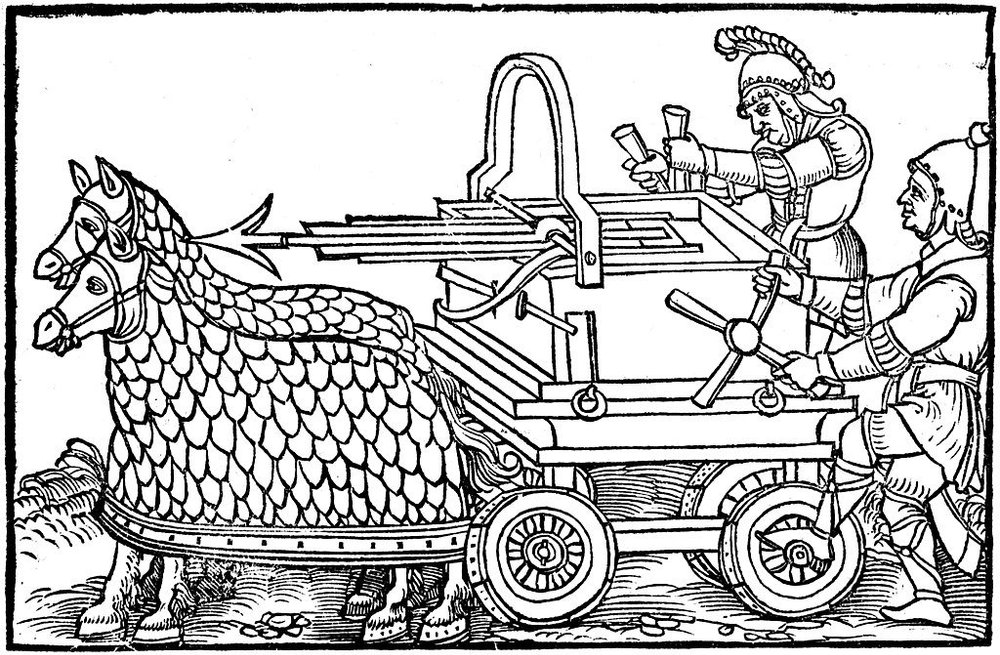

An Early Modern period depiction of two soldiers with a horse-drawn ballista.

Ancient originsThe crossbow's roots lie deep in the ancient world, with the earliest known examples emerging from China during the Warring States Period, (475 to 221 BCE), with early examples discovered from the 5th century BCE. Chinese crossbows featured sophisticated bronze trigger mechanisms and were often mass-produced. This innovation allowed large military units to wield powerful, standardised ranged weapons with minimal training. Perhaps most remarkable was Zhuge Liang's "repeating crossbow", capable of firing multiple bolts in quick succession, centuries ahead of its time.Meanwhile, in Hellenistic Greece, engineers developed the gastraphetes, (γαστραφέτης), or "belly bow," as early as the 4th century BCE. Described by Heron of Alexandria, (Ἥρων ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς), this mechanical device required the user to brace the stock against the abdomen and press down to load it. It was vital in siege warfare, where powerful bolts could be launched with force from behind fortifications.The Romans took the idea further with torsion-powered siege engines like the arcuballista and cheiroballistra, which, while not quite personal crossbows, shared similar mechanical principles. These innovations paved the way for increasingly powerful projectile weapons in European and Byzantine warfare. The weapon that changed the rulesCrossbows faded from prominence in Europe after the fall of Rome but returned with force by the 10th and 11th centuries, likely through Mediterranean trade or the Crusades. As European militaries embraced the weapon, it underwent significant improvements. The medieval crossbow, or arbalest, evolved with steel prods, cranks, and windlasses, enabling it to punch through armour at close range with devastating force.On the battlefield, crossbows proved invaluable during sieges and defensive actions, where a soldier could shoot from behind cover without requiring the strength or lifelong training needed to master a longbow. Their use at the Battle of Hastings (1066) and by Genoese crossbowmen at the Battle of Crécy (1346) cemented their reputation as serious threats.However, the crossbow was not without controversy. In 1139, the Second Lateran Council declared its use against Christians to be immoral and banned it, a rare moment when a weapon was condemned by the Church itself. This ban only heightened the crossbow's reputation as a fearsome equalizer.Unlike the longbow, which required years of practice and physical conditioning, a crossbow could be used effectively by commoners, allowing them to kill even the most heavily armored knight from afar. For some, this represented a degradation of chivalric warfare; for others, a necessary step in the evolution of combat.Compared to the longbow, the crossbow was easier to learn, had greater penetrating power, but suffered from a slower rate of fire. The longbow retained its place in English warfare, but across much of Europe, the crossbow ruled the battlefield for several centuries. Fall from graceBy the 15th century, the rise of gunpowder weapons began to overshadow the crossbow. Matchlocks and arquebuses offered greater armour penetration, required less mechanical upkeep, and perhaps most significantly, produced the terrifying psychological effect of gunfire.As mass infantry formations and volley fire tactics developed, crossbows struggled to maintain relevance. Muskets were cheaper, could be taught to recruits quickly, and their manufacture was more adaptable to emerging industrial methods. By the 18th century, crossbows had disappeared from the frontlines of most European armies, lingering only in rare instances, such as in Napoleonic-era coastal militias, before vanishing almost entirely from modern warfare. The crossbow in modern conflictDuring the Vietnam War, the Montagnard mountain tribes, an umbrella term for various indigenous groups living in Vietnam's Central Highlands, used primitive but highly effective crossbows as part of their traditional arsenal. Constructed from locally available materials such as bamboo, hardwood, and twisted plant fibers, these weapons were simple yet reliable, optimized for jungle terrain and ambush tactics. Montagnard crossbows typically featured hand-carved wooden stocks and flexible bows made from resilient native wood, firing short, sharpened wooden bolts.Despite their rudimentary design, these crossbows could deliver deadly force silently, an essential advantage in close-range forest combat and for hunting. Their quiet lethality and rugged simplicity did not go unnoticed by American troops operating alongside them. U.S. Special Forces, who often worked closely with Montagnard fighters through the Civilian Irregular Defence Group (CIDG) program, were impressed by the crossbow's stealth capabilities, ease of construction, and lack of a signature report, critical features in jungle warfare where silence often meant survival. These encounters likely inspired U.S. experimentation with modernized crossbows for specialized tasks such as cutting tripwires, silent sentry removal, and setting traps, contributing to a small but enduring niche role for the crossbow in unconventional warfare. Similarly, Russian Spetsnaz units have been known to use compact crossbows for covert operations, including breaching and wire-cutting in environments where silence is vital. Modern crossbow as a toolModern crossbows have also evolved into tactical tools, equipped with a variety of bolt types, from blunt and non-lethal projectiles to armour-piercing or even explosive-tipped variants. Some are designed to fold or collapse into survival kits, making them viable for hunting or stealth missions in hostile terrain. In specialized law enforcement units, crossbows serve non-lethal roles: deploying tranquillizers, nets, or breaching tools in hostage scenarios or urban environments where gunfire could escalate danger. Their silence and versatility have secured the crossbow a niche in military and policing contexts where subtlety and control are paramount. Archaeological evidenceArchaeological evidence has played a crucial role in uncovering the early history and battlefield use of crossbows. Some of the oldest surviving crossbow components were found in ancient Chinese tombs, particularly from the Warring States Period (475 to 221 BCE). Excavations at sites like Tomb 3 at Qinjiazui and the Terracotta Army pits at Xi'an have revealed bronze trigger mechanisms that were standardised, as indicated suggesting mass production and wide deployment in early Chinese armies.These finds demonstrate a high level of mechanical sophistication, with levers and sears similar in principle to modern firearm triggers. The Chinese crossbow was clearly not a one-off innovation but a cornerstone of ancient military strategy.In Europe, physical remnants of early crossbows are rarer but not absent. Some Roman-era torsion crossbow-like devices, such as arcuballistae and cheiroballistrae, have been reconstructed from surviving parts and contemporary descriptions. Later medieval examples, including steel prods, windlass mechanisms, and wooden stocks, have been discovered in castle ruins, riverbeds, and former battlefields, often in fragments due to degradation over time. For instance, parts of crossbow quarrels (bolts) have been found at sites like the Battle of Visby (1361) in Gotland, Sweden, one of the most archaeologically rich medieval battlefield excavations in Europe.More compelling still is the skeletal evidence of crossbow wounds, which offers chilling insight into the weapon's effectiveness. At Visby, numerous skeletons showed trauma consistent with crossbow impacts: puncture wounds in bone, especially in skulls and pelvises, where bolts had penetrated armour and lodged deep into the body. Some remains even display shattered limb bones or embedded bolt heads, testifying to the kinetic power of these weapons. The clean, concentrated puncture marks differ significantly from sword or arrow wounds, allowing archaeologists to distinguish crossbow injuries from other types of trauma. These finds confirm not only the battlefield presence of crossbows but also their deadly role in medieval warfare, where a single shot could pierce chainmail, break bone, and end a life in an instant. Legacy and influenceDespite its eclipse on the battlefield, the crossbow lives on in the cultural imagination. From medieval reenactments to video games and TV shows like The Walking Dead, it has become a symbol of silent lethality and rugged resilience.Crossbows also thrive in the fields of sport and hunting, especially in regions where gun ownership is restricted or tightly regulated. Modern hunting crossbows are precision instruments, engineered for stability and accuracy.Among engineers and historians, the crossbow remains an object of fascination. Its intricate trigger systems, leverage mechanisms, and materials engineering continue to be studied as examples of early mechanical ingenuity.Though outclassed by firearms centuries ago, the crossbow endures as one of history's most remarkable weapons, an invention that democratized lethality, challenged battlefield hierarchies, and even rattled the conscience of a medieval Church. From ancient Chinese skirmishes to the quiet footfalls of a special forces operator in the jungle, the crossbow's story is one of adaptation, resilience, and quiet power. It may no longer dominate the battlefield, but the crossbow still whispers in the shadows of warfare, silent, deadly, and unforgettable. Echoes of the CrossbowNeedless to say, the story of the crossbow is not merely a chronicle of iron, wood, and sinew, it is a reflection of humanity's evolving relationship with power, precision, and progress. From the regimented ranks of ancient Chinese armies to the rain-soaked fields of medieval Europe, and from the dense, watchful jungles of Southeast Asia to today's urban tactical operations, the crossbow has carved a singular path through military history: one of constant adaptation, innovation, and quiet endurance.Far more than a technological curiosity or medieval oddity, the crossbow revolutionized the battlefield by granting lethality to those once excluded from the warrior class. It helped dissolve the rigid hierarchies of feudal combat, where strength and aristocratic birth once dictated martial dominance. In its place came a weapon that demanded only a steady hand, a calm nerve, and the will to fire, shifting the power of life and death into the hands of the common foot soldier. The crossbow democratized warfare, frightened the nobility, and even compelled religious authorities to attempt its banishment, proof of how deeply it challenged prevailing norms.Its mechanical sophistication, particularly in ancient China, speaks to the ingenuity of early engineers who saw beyond the bow's limitations. These innovations echoed centuries later in European refinements: windlasses, goat's feet, steel prods, and complex trigger mechanisms that brought a brutal elegance to the battlefield. The archaeological record, with its telltale puncture wounds and preserved bolt tips, preserves the visceral reality of its deadly impact.And yet, the crossbow's story did not end with the thunder of muskets or the precision of rifles. Its rebirth in modern warfare, though modest, demonstrates a remarkable resilience. Where silence, stealth, and improvisation matter more than volume of fire, the crossbow endures, whether in the hands of Montagnard tribesmen defending their ancestral forests, or Special Forces soldiers operating deep behind enemy lines, The crossbow's relevance persists in situations that call for control, quiet, and calculated lethality.In a world driven by ever-advancing technology, the crossbow reminds us that simplicity, reliability, and silence still have their place. It is a weapon not only of war, but of principle: one that marries form and function, history and innovation, brutality and discipline. It is a tool of ancient armies, a relic of medieval sieges, a whisper in the dark jungles of modern combat and above all, a tribute to the enduring ingenuity of those who shaped it.The crossbow may no longer decide the fate of empires, but its legacy endures, etched in steel, remembered in bone, and still alive today. The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here. Notes:Crossbow compared to an English Longbow When comparing the advantages and disadvantages of the medieval crossbow to the English longbow, several key contrasts emerge that reflect the differing roles and accessibility of the two weapons.The crossbow's greatest advantage over the longbow was its ease of use. Unlike the longbow, which required years of training and considerable physical strength to master, the crossbow could be effectively operated by less experienced soldiers with minimal instruction. This made it ideal for militias, mercenaries, or conscripted troops, especially in regions lacking a strong archery tradition.Additionally, the mechanical design of the crossbow allowed it to achieve high draw weights through cranking mechanisms such as the windlass or cranequin, giving it the power to penetrate heavy armour at short to medium ranges, an area where the longbow could sometimes falter.The crossbow also offered greater consistency in terms of aim and accuracy due to its stable mechanical release, which reduced the influence of human error compared to the manually drawn and released longbow. This precision made the crossbow particularly effective in siege scenarios, where defenders or attackers could take time to aim at fixed targets.However, the crossbow had several significant disadvantages when compared to the longbow. Most notably, it had a much slower rate of fire, typically only 2–3 bolts per minute, leaving crossbowmen vulnerable during the lengthy reloading process. This made them less effective in fast-paced battles or open-field engagements, where the English longbow's rapid fire of up to 10–12 arrows per minute could dominate. Additionally, the crossbow was more cumbersome to carry and maintain, and its complex mechanisms were more prone to failure under adverse weather conditions, unlike the simpler and more robust longbow.Therefore, while the crossbow offered greater armour penetration and ease of use for untrained soldiers, it lacked the speed, endurance, and battlefield versatility of the English longbow. Its strengths lay in precision and accessibility, whereas its limitations made it less effective in dynamic, large-scale combat scenarios dominated by trained longbowmen. Zhuge Liang's repeating crossbowZhuge Liang's repeating crossbow, known in Chinese as the Zhuge nu, is one of the most iconic mechanical weapons in Chinese history. However, its association with Zhuge Liang may be more symbolic than literal. This device was a rapid-fire crossbow capable of shooting multiple bolts in quick succession with minimal user effort.Though crossbow technology predated the Three Kingdoms period, the repeating crossbow attributed to Zhuge Liang was notable for its simplified firing mechanism, which allowed for a high rate of fire, a crucial advantage in the chaotic skirmishes of ancient warfare.The weapon operated through a combination of a magazine-style bolt hopper and a push-pull lever mechanism. Each time the operator pulled and pushed the lever back and forth, the bowstring would automatically draw, release, and reload with a fresh bolt from the magazine. This allowed even relatively untrained soldiers or defenders in fortified positions to unleash volleys of bolts rapidly, making the weapon especially useful in close-quarters defence, ambushes, or when mounted on walls and chariots.The bolts were often poisoned, compensating for their relatively low penetrative power compared to single-shot crossbows. While Zhuge Liang (181–234 CE), the famous strategist of the Shu Han state, is often credited with inventing or popularising the repeating crossbow, historical evidence suggests the concept may have existed before his time. However, his reputation as a master of military innovation and engineering likely led to the weapon being named in his honour. Surviving versions of the Zhuge nu from later dynasties show refinements in design, but the fundamental concept of a mechanical device enabling rapid bolt fire endured for centuries in Chinese warfare, proof of its practical ingenuity.