www.thecollector.com

The Epic Story of El Cid (Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar)

Few people have come close to achieving such legendary status as Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, better known as El Cid. Throughout his life, he fought for both Christian and Muslim armies, and was greatly respected and revered by both. In fact, his tale has been told so often that history and legend have been mixed up. The primary aim of this article is to distinguish the difference between the two and tell the story of the man behind the myth.

El Cid’s Early Life

Statue of El Cid in Burgos, Spain. Source: Wikimedia Commons

El Cid was born as Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar in the northern Spanish village of Vivar in approximately 1043. His father was called Diego Laínez, and he was a cavalryman and courtier as well as a bureaucrat who had himself fought in several battles. His mother also came from aristocratic stock, although in later years the peasants would claim El Cid as one of their own.

El Cid’s first real taste of battle was in 1057 in the service of King Sancho II of Castile. He fought against the Moorish stronghold of Zaragoza, eventually making its emir a vassal of King Sancho. This was in the early years of the Reconquista, which is when Christian Spain attempted to claim its land back from the Moors (or Muslims) who had conquered much of the Iberian Peninsula since the 8th century.

At the Battle of Graus, on May 8, 1063, El Cid fought an Aragonese knight in single combat and defeated him, which earned him the nickname “Campeador,” meaning “Champion.” It was around this time that Sancho learned that his brother Alfonso VI of León was planning to overthrow him, so he sent El Cid to bring Alfonso to him to speak to him in person.

El Cid and Alfonso VI

Sancho II, c. 1312-25. Source: Spanish Digital Library

During the Siege of Zamora in 1072, Sancho was assassinated. Because he died childless and unmarried, his power passed to his brother. Therefore, Alfonso did not need to overthrow his brother, it happened naturally. However, this did not mean that he did not have any battles—physical and political—to fight.

Alfonso immediately returned from exile and took his seat as King of both León and Castile. Many contemporaries presumed that he had played some part or been involved in the dirty work of assassinating his brother.

Many senior figures forced Alfonso to swear in front of numerous holy relics that he had played no part in the assassination of Sancho II, which he allegedly did.

By 1079, El Cid had been sent to Seville on the instructions of Alfonso VI to the court of Abbad III to collect the parias (tribute) owed to the kingdom of León-Castile. While El Cid was in Seville, the Kingdom of Granada attacked the city, and El Cid helped to defend it.

At the Battle of Cabra (1079), El Cid actually helped to repel the Christian forces that were attacking the city, and he gained great respect from the Moorish troops whom he had taken under his command. They gave him the nickname “Sayyidi.”

El Cid’s Exile

Alfonso VI, conquering Toledo, Seville, Spain. Source: Wikimedia Commons

During the Battle of Cabra, El Cid turned the battle into a rout of Emir Abdullah of Granada. However, this greatly angered Alfonso VI, who, enraged at El Cid’s unauthorized expedition into Granada, exiled him. He is not mentioned in any of Alfonso VI’s documents after May 8, 1080.

It was most likely the knight’s expedition into Toledo as part of this campaign that angered Alfonso VI so much, because Toledo was a vassal of the king at the time.

However, El Cid made sure that this exile was not to be the end of him, nor just a tragic footnote in the life of this northern Spanish knight. First, he traveled to Barcelona, where his service was refused by Ramon Berenguer II.

As he had previously helped the Moors before, he soon realized: why not help them again? As a result, he returned to the Taifa of Zaragoza, where he received a much warmer welcome.

El Cid’s Service Under the Moors

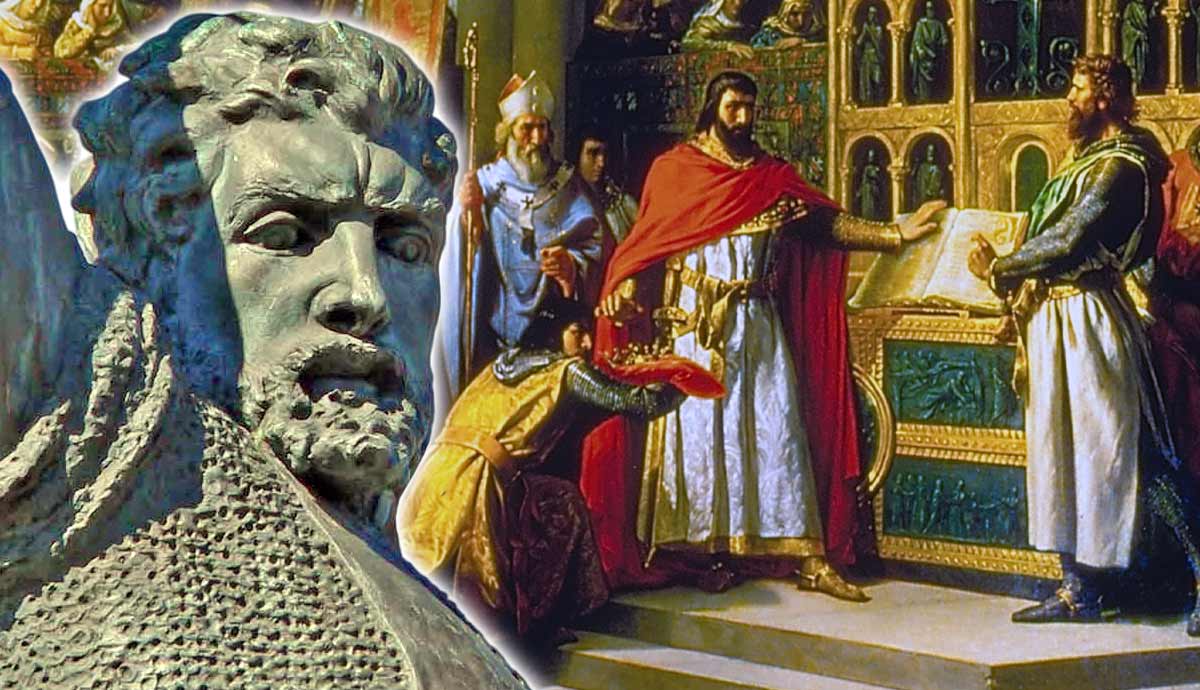

Alfonso VI swearing against his involvement in Sancho II’s murder (El Cid in the green to the left), by Marcos Hiráldez Acosta, 1864. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In 1081, El Cid offered his services to Yusuf al-Mu’taman ibn Hud, who was the King of Zaragoza. He would end up serving both al-Mu’taman and his successor, Abu Ja’far Ahmad ibn Yusuf ibn Hud, who was better known as al-Musta’in II. It was during these years that El Cid was formally given the title of “El Cid,” which means “the Master.”

He was also promoted and given the position of commander. Very few people believe that armies were diverse in the Middle Ages, but the one that El Cid commanded certainly was. It was made up of a force of Berbers, Arabs, Malians, and Muwallads. El Cid was greatly respected by his troops and the Muslim community in Zaragoza, despite not being a Muslim himself.

It was not long before the victories started pouring in for El Cid, either. In 1082, he was victorious at the Battle of Almenar, when the Kingdom of Zaragoza defeated the Taifa of Lleida under the scorching Spanish summer sunshine.

The Almoravid Dynasty, a ruling Berber Muslim dynasty, at its greatest extent, 12th century. Source: Wikimedia Commons

On August 14, 1084, he oversaw another huge victory for Zaragoza, when he defeated an Aragonese force at the Battle of Morella, where over 2,000 Aragonese prisoners were taken and many more killed.

However, the same autumn, the Christians began a siege of Toledo, and captured Salamanca the following year, which was a stronghold of the Taifa of Toledo.

The Almoravids, who were a Berber dynasty from North Africa, began an invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 1086, and they were asked to help defend the Moors from Alfonso VI’s Christian forces. At the Battle of Sagrajas in 1086, this combined force of Muslims successfully defeated Alfonso’s Christian army, keeping the southern Iberian Peninsula under Moorish control.

The Christians responded by attacking from the north, which was slightly more successful: Raymond of Burgundy and his allies captured some northern territory via siege warfare, which blocked the route between the Taifas in the eastern and western Iberian Peninsula.

El Cid’s Return From Exile

Primera hazaña del Cid, by Juan Vicens Cots, 1864, via Museo Del Prado

Alfonso panicked after realizing how strong El Cid was fighting alongside the Muslim forces, and recalled him from his exile, promising him lavish titles, lands, and money. El Cid returned, but he had his own ideas.

Although he came back, shortly afterwards he returned to Zaragoza. While the risk of Alfonso’s territories being taken over by the Almoravids was very much real, El Cid hoped that by avoiding the fighting, both armies would weaken themselves.

The Conquest of Valencia

Statue of El Cid, Burgos, Spain, c. 14th-15th century. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Perhaps the most successful moment in El Cid’s life and career came during the conquest of Valencia, which took place from 1092-94.

With his combined force of Christians and Muslims, El Cid moved toward Valencia in order to claim territory that he would use as his fiefdom—essentially enabling him to rule his own kingdom.

However, he had a few obstacles in his way, the first being the man who had turned down his services following his exile from King Alfonso VI in 1080: Ramon Berenguer II, who still ruled the nearby city of Barcelona.

El Cid defeated Ramon Berenguer II at the Battle of Tébar in May 1090 and took him prisoner. However, he was later released, and in the years to come, his nephew (Ramon Berenguer III) would marry one of El Cid’s daughters to prevent any future conflict between the two families.

Close-up of El Cid Balboa Park Statue. Source: Wikimedia Commons

As with any medieval knight worth his salt, El Cid conquered numerous towns on the way to Valencia, thus increasing the bits of territory that he now owned. He reached Valencia, which was at the time under the control of Yahya al-Qadir, and during his time in the city, El Cid began to have more and more influence over the city’s politics and organization.

In October 1092, an uprising occurred, so El Cid seized this opportunity to lay siege to the city. In December 1093, an attempt to break the siege failed, so El Cid still held the upper hand. The siege formally ended in 1094, and while sometimes called the Siege of Valencia by some historians, many now refer to it as El Cid’s Siege of Valencia, showing the power and authority he had over it. He had now carved out his own piece of territory on the Mediterranean Coast.

While he ruled the city under Alfonso VI, in reality, he was fully independent, and Valencia during this time became a semi-independent kingdom. Both Christians and Muslims were welcome in the city, which is no surprise, seeing as El Cid was greatly respected by both. Christians and Muslims also served together in the city’s army.

El Cid’s Death and Legacy

El Cid and Jimena’s Tomb, Burgos Cathedral. Source: Wikimedia Commons

El Cid would live comfortably in Valencia for the rest of his life, alongside his wife Jimena Díaz. The Almoravids briefly attempted to besiege the city, but El Cid put an end to this swiftly, and the couple would live there peacefully until El Cid’s death in 1099, aged around 56 years old.

Valencia was captured by Mazdali in 1102, and Jimena fled with El Cid’s body to where it was originally buried, in Castile, in the Monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña. However, it is now interred at Burgos Cathedral, not far from his birth village of Vivar, which is now called Vivar del Cid.

While it may be easy to draw a conclusion that paints El Cid simply as a fortunate mercenary, he was much more than that. Mercenaries rarely reached the stage of commanding an army, and even if they did, most of the time they would leave and look for the next-highest bidder for their services.

Throughout his military career, El Cid was highly sought after, and the efforts he put in at the right time ensured that he was destined to write his name into Spanish, Christian, Moorish, and Muslim legend forever.

He defended the Muslims when the Christians attacked, and even though Alfonso VI exiled him, he returned to continue the Reconquista under his name.

El Cid is deservedly one of the most celebrated heroes of the Reconquista and deserves to be held in such high esteem in the histories of numerous religious and ethnic groups to this day.