www.thegospelcoalition.org

How Leviticus Deepens Our View of Substitutionary Atonement

From the beginning, Christian theology has argued that the sacrifices and offerings prescribed in Leviticus were types of Christ. And much of that theology, especially from the Reformed tradition, has argued that these sacrifices and offerings typified a penal-substitutionary death.

As one who gladly and gratefully stands in the Reformed tradition, I affirm a penal-substitutionary reading of Levitical sacrifice—and of Christ’s work, in which the promise and pattern of Levitical sacrifice find fulfillment. But I also affirm the need to revise, or at least refine, the standard argument for a penal-substitutionary reading. Our reading of Levitical sacrifice needs close attention to the book’s narrative context.

Standard Argument

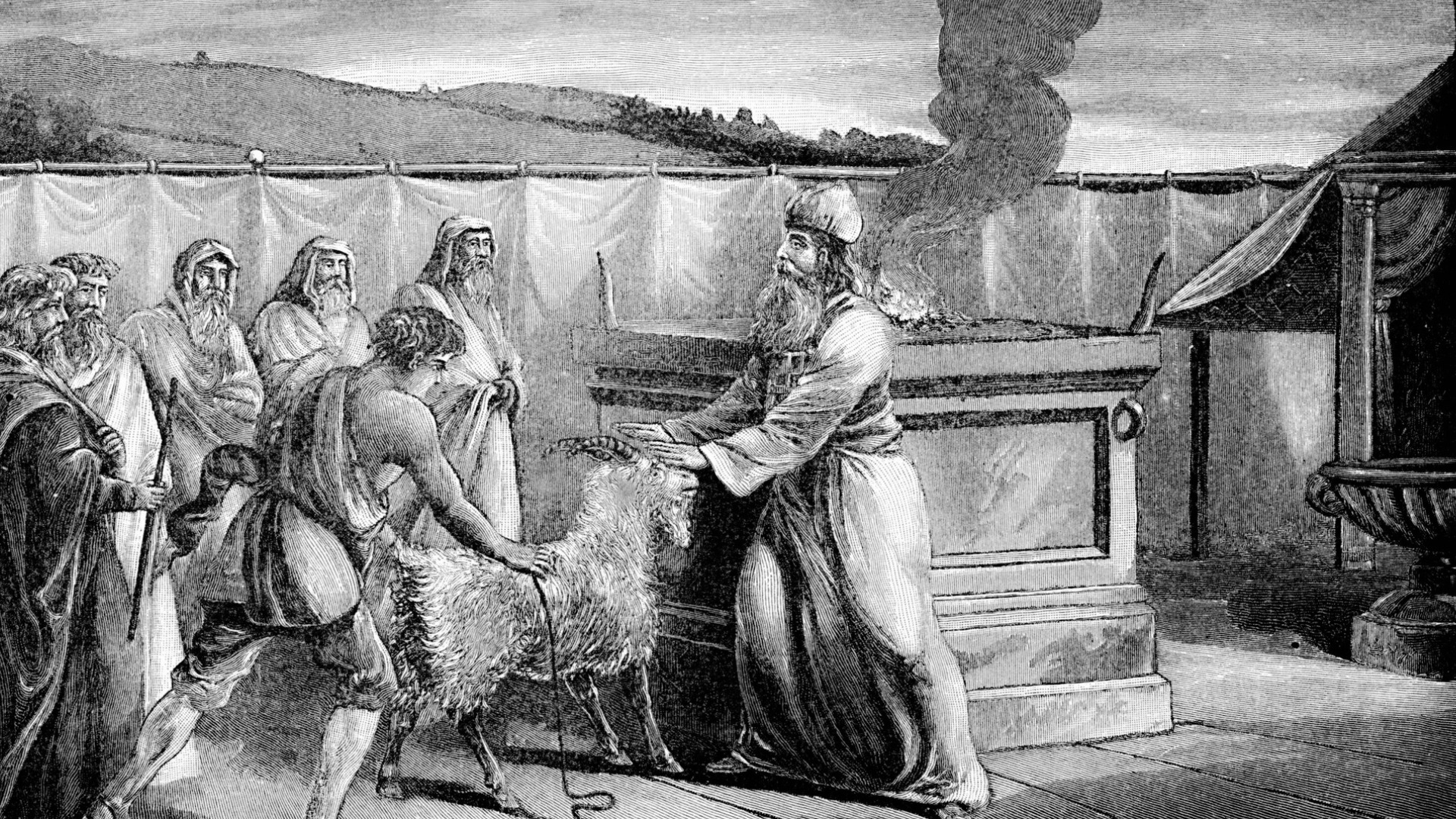

Consider the standard argument. When the offerer appeared before God at the tabernacle and, standing beside the altar, placed a hand on the head of his offering, it represented the imputation of sin. The slaughter of the offering that shortly followed was the essential or definitive act of sacrifice. And when the priest subsequently placed the sacrificial blood on the altar, the blood represented a substitutionary death that made the offerer acceptable. Thus, atonement was made.

This argument’s virtues are considerable—the close attention to the text, high regard for canonical context, and deep concern for the church and its mission. But since at least Faustus Socinus in the late 16th century, the exegetical pillars of the standard Reformed reading have been challenged, and that challenge has been somewhat successful. In particular, the Reformed reading of the hand-laying (or hand-leaning) rite is uncertain; it was likely intended to signify some notion of identification between offerer and offering, not a true imputation of sin.

There are difficulties, too, with a too-quick and too-exclusive equation of sacrificial blood with death. We must be able to give some account of the clear statement of Leviticus 17:11—that there is life in the blood of the offering, and that blood “makes atonement by the life,” not by symbolizing a substitutionary death. Any case for penal substitutionary atonement in Leviticus has to be able to speak of atonement through the offering’s life, not just its death.

When two pillars of the standard argument are weakened, the entire structure begins to wobble. These two pillars of atonement need further support, and the material for that reinforcement is found in Leviticus’s wider narrative context.

Levitical Story

Essential to a sound reading of Leviticus and its rituals is recognizing the book’s narrative context. As Gordon Wenham reminds us, Leviticus is fundamentally a narrative, and the continuation of a narrative. Rules and regulations may abound in the text, but they’re nevertheless presented as the deliverances of a series of divine speeches within an ongoing narrative. The laws have a setting within Israel’s history.

At the time of Leviticus’s writing, Israel is still at Sinai, the site of the fiery theophany; the Lord—holy, mysterious, and majestic—is still instructing them in his covenant; and Moses is still mediating. This setting affects the way we hear the instructions, as it highlights the mediatorial role of Levitical sacrifice and its function of making an approach to God possible.

When we see Levitical sacrifice in light of the creation story, its penal-substitutionary element becomes more evident.

Of course, the Sinai covenant makes sense only in light of the larger Exodus narrative. And the Exodus narrative leads us back to the call of Abraham, issued in response to sin and its destructive consequences, taking us all the way back to the story of creation.

So Leviticus is set not only in the context of the Sinai covenant but also in the much larger context of creation, sin, and redemption. When we see Levitical sacrifice in light of the creation story, its penal-substitutionary element becomes more evident.

Commentators often note the relationship between the construction of the tabernacle and that of the cosmos. Both are “built” by the Word of the Lord: the cosmos by divine fiat, the tabernacle by God’s command and Moses’s obedience. And certain features of the tabernacle appear to be symbolic of the garden of Eden—the eastward-facing entrance, the cherubim on the ark and the curtains, and, perhaps most significantly, the presence of God “walking” among his people (Gen. 3:8; Lev. 26:11–12). For these reasons and more, L. Michael Morales concludes that the tabernacle constituted an invitation to return to Eden after Adam’s sin. The sacrifices were the God-ordained means for doing so.

Return to God Through Death

From this vantage point, we can already see that Levitical sacrifice constituted a ritual return to God. But, significantly, this Levitical return to God ran through death.

According to Leviticus 1:3–9, the offerer who has selected a suitable offering and led it to the tent arrives at the tabernacle and passes through the eastward-facing entrance of the grounds. As he does so, he immediately encounters the altar. There, he lays a hand on his offering, slaughters it, and butchers it—all of which highlight the offerer’s personal involvement in the death of his offering.

Only then, after this identification and death have taken place, does the offering actually come into contact with something holy. Only after the slaughter do the priests take the animal; only after the slaughter is the offering placed on the altar; only after the placement of the slaughtered animal on the altar is the offering “received” by God and the offerer thereby assured of his acceptance.

Only after the death of his offering, then—a death in which the offerer is deeply involved—does the offerer reach his goal of reception into the holiness of God. Only by death can the offerer symbolically return to Eden.

Reinforced Pillars

In this telling of the Levitical story, the weakened pillars mentioned above are reinforced. Blood is a symbol of life, not death. Yet the blood placed on the altar is that of an offering that, after being identified with its offerer, was put to death. Atonement is made “by the life,” but this life has passed through the death required by the offerer’s sin.

Atonement is made ‘by the life,’ but this life has passed through the death required by the offerer’s sin.

The hand-leaning rite is better said to signify identity, not imputation. But that identity need not be thought to exclude all thought of imputation. The offering shares in the requirement, created by sin, of passing through death before returning to God. The offerer then shares in the offering’s reception into the holy places. This reveals a strong identity between offerer and offering, an identity that means more than imputation but not necessarily less.

These reinforced pillars give us a strengthened account of penal substitution in Levitical ritual, one that has been refined by the challenges that happily send proponents of penal substitution back to the text. The image of the slaughtered lamb may take on a slightly different color in this account. But it still proclaims Christ as our substitute.