www.thegospelcoalition.org

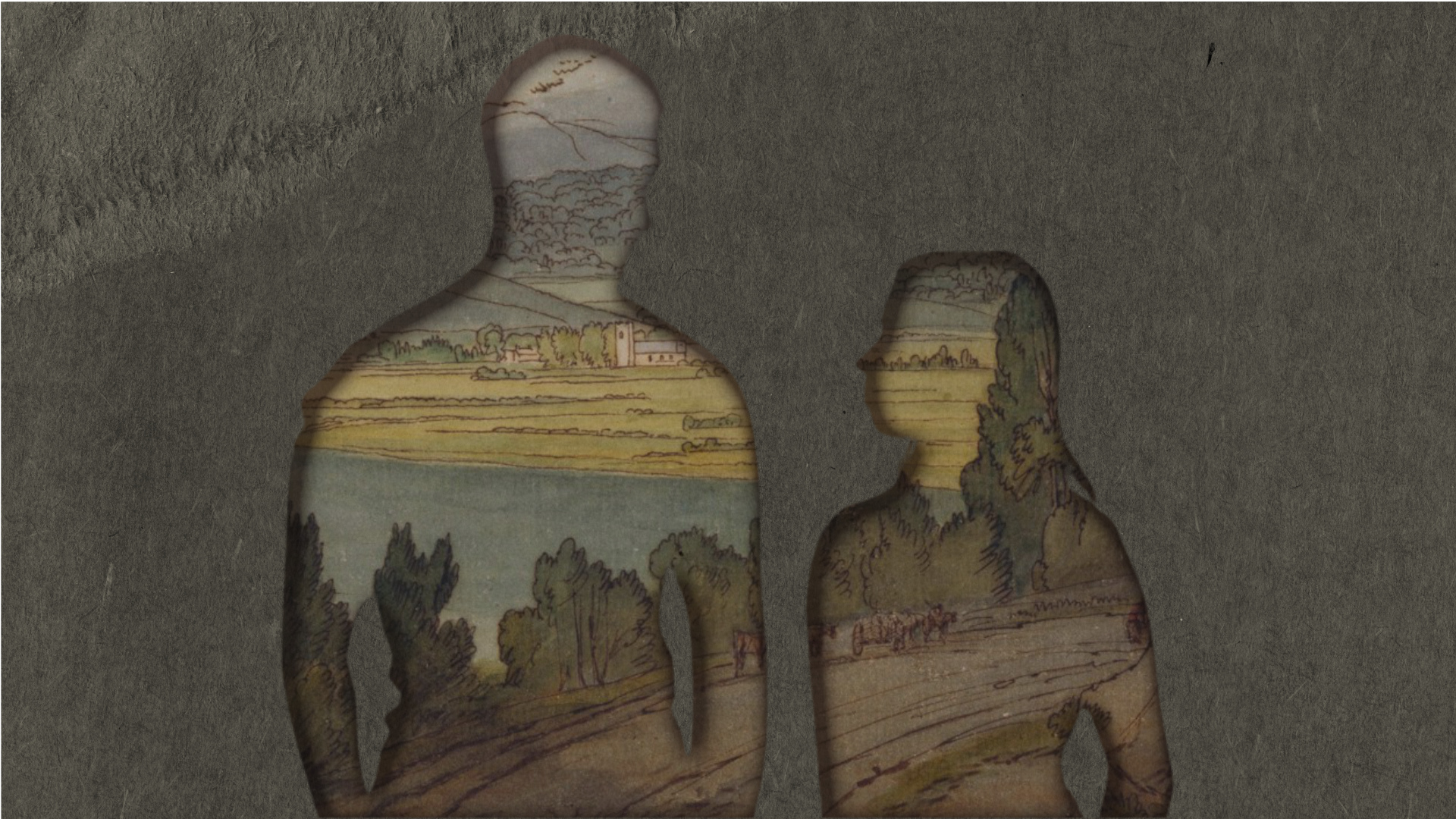

How Should We Define Biblical Manhood and Womanhood? Trace the Arc of God’s Design.

Near the end of C. S. Lewis’s science-fiction novel Perelandra, his protagonist, Dr. Elwin Ransom, saw two idyllic forms—the celestial guardians of Mars and Venus:

Malacandra [Mars] was like a rhythm and Perelandra [Venus] was like a melody. . . . The first held in his hand something like a spear but the hands of the other were open. . . . What Ransom saw in that moment was the real meaning of gender.

Many today will bristle at Lewis’s Neoplatonic description of gender ideals. But complementarians should at least agree with the Inkling’s assumption that manhood and womanhood aren’t merely physical concepts. Gender begins with our sexed male and female bodies, but it doesn’t stop there. We should affirm for ourselves and our children that even if the two terms are sometimes difficult to define, manhood and womanhood are larger, teleological realities.

God’s Purposeful Design

In theology, “teleology” involves looking at the nature of God’s created works to uncover the purpose in his design. As Catholic scholar Abigail Favale writes, “The ‘whatness’ of a thing, its essential identity, is connected to its purpose.” Complementarians look at biological sex and gender, the psychosocial aspect of sex, through a teleological lens. We believe there’s a God-designed link between being male or female and the doing roles God has called us to inhabit as men and women.

In both the Danvers Statement from the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (1988, affirmations 1 and 2) and The Gospel Coalition Confessional Statement (2007, article 3), we have confessed not only that God made our first parents male and female with equal dignity and value but also that after creating them, God immediately commissioned the man and woman, giving them work to do (Gen. 1:26–27). As complementarians, we believe there’s a purposeful connection between the way God made us and what he’s made us for.

Complementarians have argued from Genesis 1–2 that, by God’s design, the “essence” of our biological sex and the gendered “roles” we inhabit in our families and church communities are linked. As Kendra Dahl writes, “Each of us is born with . . . [an] intrinsic desire to know the end for which we’re created, rightly seeing a straight line between our being and our doing.”

But though complementarians keep essence (being) and function (doing) together, we’ve often been tempted to emphasize one aspect of God’s design over the other.

Emphasizing Function in Response to Feminism

Danvers’s framers wrote to combat “a rising tide of feminism that they perceived within evangelicalism.” The statement rejects the feminist assumption that male-dominated society has imposed traditional gender norms on women, and it promotes motherhood, homemaking, and vocations historically performed by women. In their response to evangelical feminism and egalitarianism, Danvers’s framers emphasized what it means for men and women to relate to one another functionally.

Though complementarians keep essence (being) and function (doing) together, we’ve often been tempted to emphasize one aspect of God’s design over the other.

In complementarianism’s seminal text, Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (RBMW), mature masculinity is defined as the “benevolent responsibility to lead, provide for and protect women” at home, in the church, and in society. It also says mature femininity is “a freeing disposition to affirm, receive and nurture strength and leadership from worthy men.” This emphasis on men and women’s sociological differences has been complementarianism’s most consistent note, and it’s often been a great strength.

But as Gregg R. Allison writes, “RBMW, while well-meaning for the context it addresses, did not penetrate below the surface to define manhood and womanhood in terms of nature or essence.” As a result, it left gaps in application.

RBMW made marital (husband and wife) and ecclesial (elder and congregant) roles paradigmatic for all male-female relationships. The Bible describes these roles in terms of sacrificial headship/authority and submission (Eph. 5:22–24; Heb. 13:17). But the dominant way Scripture talks about men and women in the church is, as Patrick Schreiner observes, “through the image of sibling.” In brother-sister relationships, headship and submission don’t come into play. What does manhood and womanhood look like in these contexts? How is it expressed between brothers, sisters, and friends? A more robust complementarianism would be prepared to answer questions like these.

The Danger of Overemphasizing Function: If we skip over essence to function and overemphasize biblically prescribed roles, we can give the impression that manhood and womanhood are life goals to achieve rather than gifts to steward in accordance with God’s design. In this way, we leave the door open for narrow traditionalists to smuggle legalism into complementarian teaching. It can sound like this: “You aren’t a real man until you have a job and provide for your family.” “You aren’t a true woman unless you set up house as a trad wife and mother.” Such statements put doing before being, confusing root and fruit.

Emphasizing Essence in Response to Transgenderism

If RBMW emphasized roles in the face of feminism, conservative evangelicals over the past decade have begun to stress men and women’s essential and beautiful difference in the face of transgenderism. We’ve emphasized the truth that maleness or femaleness is imprinted on a person’s body before it’s ever expressed in procreational, developmental, and relational differences. As Allison argues, all conservative evangelicals, whether complementarian or egalitarian, can affirm that “by divine design, women and men are significantly different.”

As evangelicals have engaged public discourse over women’s sports and experimental “gender-affirming” medical procedures, we’ve clearly taught both that men and women are biologically distinct and that the Bible prohibits a willful disregard of one’s biological sex in an effort to be seen as, or identified with, the opposite sex (Deut. 22:5).

Conservative evangelicals over the past decade have begun to stress men and women’s essential and beautiful difference in the face of transgenderism.

Conservative evangelicals have been clear about the essential difference between the sexes, and among many complementarians the emphasis on function—especially related to roles within the church—has continued. But at the same time, descriptions of day-to-day gender expression and roles are often vague.

Scholars like Gracilynn Hanson acknowledge that “the various disciplines of science and philosophy have recognized men and women generally think and behave differently.” But because we want to emphasize women and men’s common dignity and avoid merely repeating traditionalist stereotypes, some complementarians today avoid saying anything about how biblical manhood and womanhood function socially. We’ve been clear that transgender ideology is unbiblical, but is that all we can say about gender expression? Isn’t there also something positive we can say about lived manhood and womanhood? A complementarianism that reaches the next generation must answer these questions, too.

The Danger of Only Emphasizing Essence: Both complementarians and egalitarians can emphasize men and women’s common creation in God’s image, their equal dignity, and their equal capacity to embody human virtues. Both can affirm the biological-sex binary and men and women’s interdependence—the truth that we need each other to fulfill the creation mandate and the Great Commission. But as complementarians, if we only understand men and women in terms of essence and never disciple our people on how to navigate the weeds of gender expression and function, we’re quietly abandoning the foundations of our movement. More importantly, we’re leaving our congregants and kids without a clear sense of how their maleness and femaleness relates to the way they live each day.

Better Definitions

Elisabeth Elliot once said, “I can’t pin [masculinity and femininity] down once and for all, or spell out all the ramifications, or dictate the details of how they ought to look in late twentieth-century America. They are, I admit, elusive symbols.” I get what she’s saying. Like Ransom’s ethereal vision, a clear definition of manhood and womanhood can be hard to trace, but as Elliot knew, that fact shouldn’t keep us from trying.

In 2020, Schreiner proposed these working definitions of manhood and womanhood:

The fundamental meaning of masculinity is sonship, brotherly love, and potentiality toward paternity.

The fundamental meaning of femininity is daughterhood, sisterly love, and potentiality toward maternity.

Unlike early complementarians, Schreiner doesn’t make gender roles in marriage and church leadership the paradigm for masculinity and femininity. He rightly refuses to read the functions of authority and submission into every gendered relationship. But at the same time, Schreiner makes clear that sexed bodies should set the trajectory for gender expression.

Make Teleology a Part of Your Discipleship

Following Schreiner, parents and church leaders should make appeals to God’s design a part of their discipleship. As I’ve written before, we must teach children and youth what it means to be a “godly son or daughter, brother or sister, wife or husband, mother or father.”

Our sons are male, and if they develop typically, they’ll grow to be adult men with the strength of a male musculoskeletal structure. In light of this design and their potential roles as husbands and fathers, we should train boys to take sacrificial initiative, work hard, and protect others. Our daughters are female, and if they develop typically, they’ll grow to be adult women with bodies that can incubate and sustain a baby’s life from conception through infancy. In light of this design and their potential roles as wives and mothers, we should train girls to be influential helpers who cultivate the relational structures necessary to nurture others.

I’m not suggesting men don’t contribute to society’s relational structures; a father shouldn’t be all authority with no nurture. Nor am I saying women should never provide for and protect their families and communities; there are too many biblical examples, such as the wise woman of Proverbs 31, to the contrary. But as Jordan Steffaniak observes, while “human beings of either sex can practice every virtue indiscriminately . . . our biology does determine that men have differing levels of capability than women [and vice versa] to display particular virtues.”

Prescription and Prudence

For this reason, I think it’s necessary to teach children and youth how to steward with Christlike character the unique strengths God gave us when he made us male and female. Such appeals to teleology prepare young people to live out healthy gender expression even if they never get married and become parents. As Wendy Alsup writes, “Whether individuals ever have biological children, the two sexes are integral in bearing and growing spiritual children.” Each sex’s importance can be lost if we fail to celebrate the distinct gifts each contributes to the home, church, and world.

It’s necessary to teach children and youth how to steward the unique strengths God gave us when he made us male and female.

Having said this, I don’t think our appeals to God’s design always need to be prescriptive. Instead, like Alastair Roberts observed recently, they can be “prudential.” I’m not going to dictate particular careers for my daughters, but when we talk about the college majors and job paths they’re considering, I’m also not afraid to ask, “How does this opportunity fit with your gender? How might walking down this road affect you if in a few years you want to get married and have kids?”

‘It Is Not for Nothing That You Are Named’

Lewis ends Perelandra with Ransom’s vivid vision of masculinity and femininity, but that’s not where the novel’s reflections on God’s design begin. Themes from Genesis 1–3 give shape to the book’s entire plot. At the turning point, Ransom confronts a demon-possessed Un-man who, like the biblical Serpent, tempts Venus’s first Lady to transgress the one law God gave her.

Unlike the Genesis 3 narrative, Perelandra’s temptation account extends for chapters. During this prolonged conversation, God puts both the Un-man and the primordial Lady to sleep, leaving Ransom to reflect on why he’s there at all.

Ransom wonders what part his presence on Venus will play in God’s design for the planet. Only one purpose makes sense: Ransom must stop the Un-man. But, he wonders, how could he—a man who’s not stereotypically masculine but is instead a “sedentary scholar with weak eyes and a baddish wound from the last war”—possibly defeat an immortal enemy? Then, Ransom hears God’s voice: “It is not for nothing that you are named Ransom.” At that moment, the middle-aged scholar knew that even if it came to violence, he’d fight for the sake of the Lady—his sister. What he would do, how he would act, would follow the arc of the story God had written for him.

God has designs for us just like he had for Ransom. It’s not for nothing that we’re named man and woman. When we define biblical manhood and womanhood, when we teach our children about masculinity and femininity, let’s not miss his purpose. Let’s trace the grain of reality, following the arc of God’s design from being to function, and let’s help the next generation do the same.