www.thecollector.com

6 Famous Abolitionists You Should Know

The first African American slaves arrived on the Virginia coast in 1619, marking the beginning of a long and tragic history. Not only would the institution of slavery last for over 200 years, but its ramifications echoed long after in the form of racism and oppression—challenges still present today. In order to bring about the changes that would end the system of slaveholding in the United States, political and sometimes quite literal blows were struck. On the front lines were abolitionists who made freedom their life’s work, fighting to make a difference in the lives of future generations.

1. Frederick Douglass

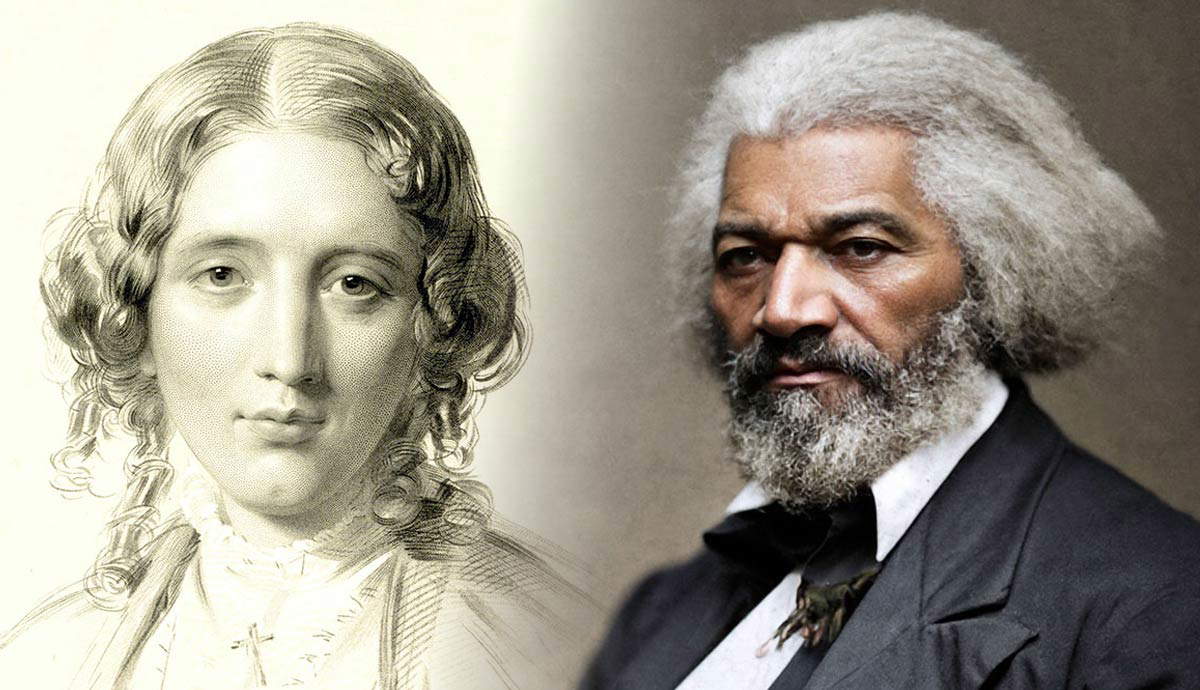

Frederick Douglass, circa 1879. Source: National Archives and Records Administration via Wikimedia Commons

Born enslaved, Frederick Douglass rose from subjugation to become one of the United States’ first civil rights leaders. Douglass was born in Maryland in February 1818, and not knowing his exact birth date, later selected February 14. His mother, Harriet Bailey, was also enslaved, and his father was unknown and believed to be a white man, perhaps Aaron Anthony, the man who claimed ownership over him.

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey had several siblings, and spent a great deal of his childhood in the care of his grandmother, Betsey Bailey. His mother died in 1826 and Frederick was moved between multiple masters. Young Frederick seemed to recognize the importance of literacy, and asked a member of his master’s household to teach him to read. She did, until the master put a stop to it. Still, in the following years, Frederick continued to work on his reading and writing skills in private.

Frederick Douglass in the 1840s. Source: Explore PA History via Wikimedia Commons

After 20 years of confinement, Frederick fled slavery in 1838, heading north and changing his last name to Douglass. Arriving in New York City, he married a young freedwoman named Anna, who had aided in his escape. Deciding New York was too risky, the couple moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, and went on to have five children.

Douglass worked as a laborer and became involved in local antislavery causes. He was an excellent speaker, and soon, his skills were in demand by groups eager to hear about his experiences as a slave and his promotion of abolitionist views. He even published his first autobiography in 1845. Frederick’s growing fame made him vulnerable to those who sought to recapture him, and he spent time in Europe to avoid slave catchers. However, his friends in the abolitionist movement volunteered to purchase his manumission free and clear, and Douglass was able to return to the US a free man and moved his family to Rochester, New York. He continued his abolitionist work and became involved in politics, contributing to the Underground Railroad, and starting his own newspaper, the North Star. Frederick continued to write, not only for his paper but also in the form of additional books about his experiences.

Douglass, his second wife (right), and her sister. Source: National Park Service via Wikimedia Commons

When the Civil War drew to a close, Douglass wasn’t satisfied with simple emancipation for America’s slaves. He continued his fight, focusing on equal citizenship, arguing that freedom was nothing without rights. Women’s rights became another focus of his efforts. He moved to Washington, DC, and served in various positions under five different presidents. Anna died in 1882. In 1884, Douglass remarried, this time to Helen Pitts, a white woman 20 years his junior, sparking controversy. The pair spent time traveling to Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean. Douglass died at 77 from a heart attack and remains today one of the pivotal figures of American abolition.

2. John Brown

John Brown was unafraid to use violence to make his point. Here, his trial is depicted. Source: National Archives via Wikimedia Commons

John Brown believed that action was the only way to address slavery, and he wasn’t afraid of violence to achieve his means. He grew up in an abolitionist family, and spent his early life working a variety of jobs and contributing to various antislavery causes. He gave land and resources to fugitive slaves, assisted with the Underground Railroad, and established the League of Gileadites, which worked to protect escaped slaves from their would-be capturers.

Brown met Frederick Douglass in 1847, at which time Douglass made a remark that illustrates Brown’s fervency for the abolitionist cause, saying it was as if “his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery.” Brown eventually moved to Kansas, the site of bloody controversy in regard to the issue of slavery. The territory was clearly split between pro and anti-slavery believers, and “Bleeding Kansas” ensued. Brown was in the thick of it, leading a group of antislavery guerilla fighters and killing proslavery settlers without mercy. He brought his plans east again, gathering a group of 21 men to raid the military arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in 1859. The plan was to use the captured weapons to create an abolitionist army that would free slaves by force. Brown was wounded in the raid and captured. He was tried and convicted of treason and was hanged on December 2, 1859. He remains a controversial figure, with some disagreeing with the brutality of his methods, while others champion his unwavering dedication to the cause.

3. Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe. Source: National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons

Upon meeting her in 1862, President Abraham Lincoln allegedly remarked to author Harriet Beecher Stowe, “So, you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!” Indeed, Stowe was the best-selling author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Life Among the Lowly. The book is argued by some to be the most influential novel ever written by an American. Stowe highlighted the plight of the slaves in the US, and conditions in the slaveholding South, bringing attention to the truth of the industry and the stark contrasts between the North and the South.

Born into an abolitionist New England Family, Stowe infused her tale with Christian themes, appealing to the spiritual side of her readers and questioning whether or not slavery and Christianity could ethically exist together. Stowe’s writing was widely read, and made the idea of the abolitionist movement seem more rational to those who were suspicious of its potentially radical ideas. The book was banned in some areas of the South or denounced as pure fiction, leading Stowe to publish a follow-up companion book that provided documentary evidence to support her writing. Stowe once argued that “there is more done with pens than with swords”, and if the legacy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin is any indication, she was exactly right.

4. Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman photographed by Horatio Seymour Squyer, circa 1885. Source: National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons

Araminta Ross was born into slavery in Maryland in 1822. The woman, later known as Harriet Tubman, had her first experience with attempted escape when she was 13. Running errands for her master, she observed a slave attempting to flee. She refused to assist the slave catcher in locating the escapee, and in his anger, he threw a two-pound weight, hitting Ross in the back of the skull, fracturing it. For the rest of her life, she dealt with a variety of consequences, including chronic headaches, seizures, and narcolepsy. In addition, she seemed to have a strong desire for liberation.

She married in 1822, changing her last name to match her mother Harriet’s, and taking her husband John Tubman’s last name. Harriet and her brothers made their escape in 1849, with their sights set on Philadelphia. Though her brothers’ fears caused them to turn back, Harriet reached her destination, connecting with abolitionists upon her arrival. She returned south in 1850 to aid family members in escaping, and from then on, dedicated her time to serving as a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, aiding other slaves on their journey north.

Over the course of 10 years, Tubman brought 70 people north, allegedly accruing a bounty as high as $40,000 (over 1.5 million dollars in modern money) on her head. After retiring from the “Railroad”, Tubman worked as a nurse during the Civil War, and as a spy for the Union. She became the first woman in history to organize and lead a military raid when she led a group of scouts into South Carolina to free approximately 750 slaves and burn numerous Confederate plantations. She was inducted into the Military Intelligence Corps in 2021.

5. William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison was a newspaperman and a famous abolitionist. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Writer William Lloyd Garrison used the press to make his voice heard, speaking out about the evils of slavery for over three decades. He joined the abolitionist movement in 1830 at the age of 25. In January 1831, he published the first issue of his antislavery newspaper, The Liberator. Garrison voiced the opinion that the only option was immediate emancipation for all slaves, a viewpoint that was radical even among abolitionists at the time. Still, Garrison refused to budge, and even attracted a following. He believed that the US Constitution was pro slavery, leading to complicated relationships with some fellow abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass. Garrison published his last issue of The Liberator at the conclusion of the Civil War, wrapping up after 1,820 consecutive issues.

6. Anthony Benezet

A historical marker in Pennsylvania denotes the location of Anthony Benezet’s former home. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Benezet, a French immigrant to America, was a Quaker who made an impact through education. He believed education should be available to all people, including women, African Americans, and those with disabilities. He created a number of inclusive educational programs throughout Pennsylvania. Benezet was an abolitionist who believed that the idea of black inferiority was false and baseless. He wrote to a number of organizations and people, including Queen Charlotte, wife of King George III, London Yearly Meeting, and the Quaker Church, calling on them to denounce and eradicate slavery. His anti slavery pamphlets spread not only through America, but became popular abroad as well. Upon his death in 1784, Benezet willed his assets to be used to support the education of African American and Native American peoples.