www.upworthy.com

Local newspapers are deleting old crime stories to give ex-convicts a second chance

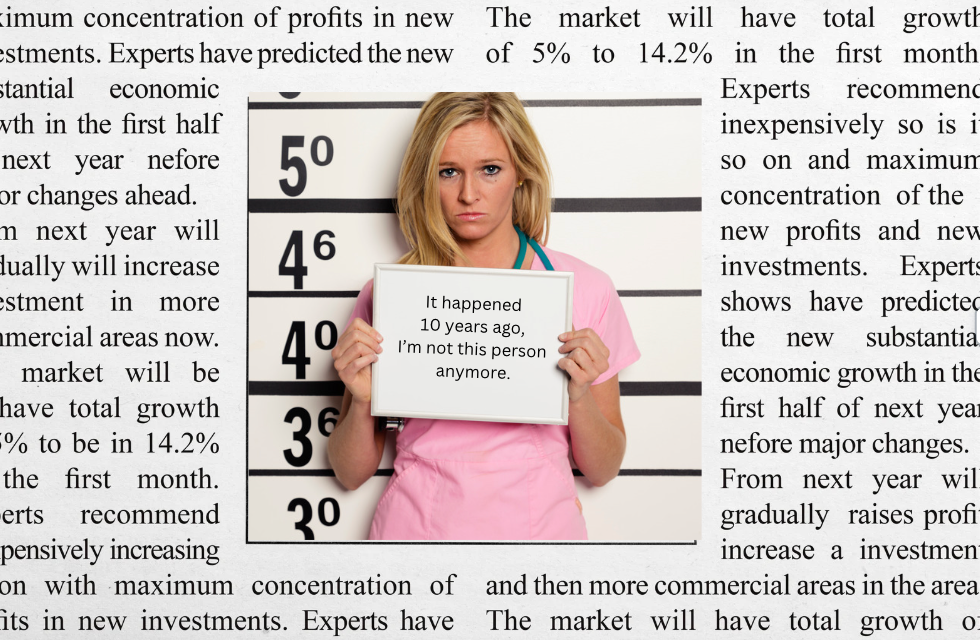

A growing number of newspapers in the United States are doing their part with the rehabilitation of former criminals and helping them achieve new lives. How? By literally deleting their old ones.Bringing it to worldwide attention by The Guardian, several American newspapers and their websites have taken down and erased old reported stories of local crimes. This movement was spearheaded in 2018 by Chris Quinn, an editor at Cleveland.com, who founded a “right to be forgotten” edict for his publication. Multiple requests from readers to pull down old reports about them or simply remove their names from the stories inspired Quinn’s movement. One such example the Quinn experienced was a woman in the health field who at one point stole some drugs from her job. She served her sentence and not only was deemed completely rehabilitated by a judge, but had the records of her crime sealed. In short, no one would be able to find records of her crime today through official channels. Google, however, doesn’t forget.

Having a mistake from your past available online makes it more difficult during job interviews.Photo credit: CanvaWhile she tried to start a new career outside the medical field (she accepted the fact that her actions made it so she couldn’t reclaim her medical license), any potential employer could see her mugshot from Cleveland.com’s news coverage of her past crime upon just Googling her name. This made it difficult to move forward by obtaining a new job for her new life.She’s just one of millions of people going through this struggle. Per The Sentencing Project, more than 60% of formerly incarcerated people are unemployed within one year of being released, and as many as one in three Americans have a criminal record of some sort. Given that most job applications require a background check, employers can unearth past offenses of job applicants through a simple Google search, which can influence whether or not a person can be hired. This means that a good chunk of Americans are losing out on opportunities due to being judged by a mistake they made deep in the past, some of which are decades-old.

With their stories still available to the public years later, some rehabilitated offenders still feel imprisoned by their past.Photo credit: Canva“We heard from many people about the pain this caused for them, especially those who had turned their lives around and were striving to be better people,” said Quinn in a 2022 op-ed updating their readers. “In 2018, we started our Right to be Forgotten project, accepting applications from people to remove their names from dated stories about them. We received 10 to 15 a month on average, and a committee of editors considered them.”Other publications took notice and in recent years started enacting their own “right to be forgotten” practices, such as The Oregonian and The Boston Globe. “Our response up until now has been that we do not remove accurate stories, as they are a snapshot of historical fact,” wrote Therese Bottomly, editor at The Oregonian. “But news organizations are coming to realize that such stories linger and affect lives in ways that can be outsized compared to the incident itself.”Each publication has their own standards as to what stories get taken down and which ones remain online. Certain factors come into play in making that decision such as how long ago the incident was first reported and the severity of the crime committed. Some publications may elect to keep stories as written, but remove any mugshots that identify the persons involved. In any case, the overall focus is universal: Not letting a person’s past define their future.

A clean slate means a fresh start and a new road for the rehabilitated.Photo credit: Canva