reactormag.com

Read an Excerpt From Hellions by Julia Elliott

Excerpts

short story collection

Read an Excerpt From Hellions by Julia Elliott

A story collection that blends folklore, fairy tales, Southern Gothic, and horror

By Julia Elliott

|

Published on February 12, 2025

Comment

0

Share New

Share

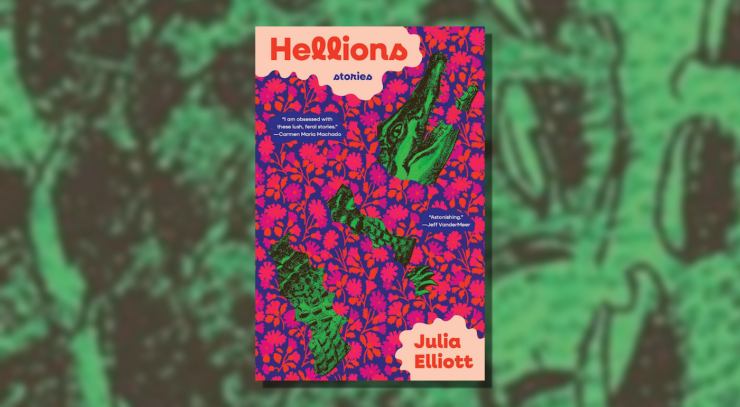

We’re thrilled to share the short story “The Maiden” from Julia Elliott’s Hellions, a brand new collection reveling in the collision of the familiar with the wildly surreal—publishing with Tin House on April 15th.

In a plague-stricken medieval convent, a nun works on a forbidden mystic manuscript. In rural South Carolina, an alligator named Dragon becomes a beloved pet for a precocious, tough-talking twelve-year-old. During a long, muggy July, an adolescent girl finds unexpected power as her family obsesses over the horror film The Exorcist. On the outskirts of a Southern college town, a young woman resists the tyranny of a shape-shifting older professor as she develops her own sorceress skills. And at a feminist art colony in the North Carolina mountains, a group of mothers contends with the supernatural talents their children have picked up from a pair of mysterious orphans who live in the woods.With exuberance, ferocity, and astounding imagination, Julia Elliott’s Hellions jumps from the occult to the comic, from the horrific to the wondrous, in eleven stories of earthbound characters who long for the otherworldly.

The Maiden

Our parents said the Watts were lunatics for putting a trampoline in their backyard, out behind their garage full of souped-up dirt bikes, in the tiny meadow still strewn with their dead horse’s droppings, out where a honey locust had just burst into bloom. We didn’t believe it until we saw it: hoisted by silver tubing, its round nylon bounce mat glimmering like a black lagoon in the endless summer light. We watched from the woods the first day of its glory, the Watts boys kickboxing in the air, performing backflips, torpedoing their agile bodies off the side and landing like Olympians in the long grass.

Our parents said we’d knock out our teeth, break our necks, paralyze ourselves. Our parents said we’d suffer concussions, bashed noses, ruptured organs, broken limbs. But how could we resist the miracle of fake flight, the mockery of gravity’s law? How could we resist the cool kids that gathered each day in the fragrant shade of the honey locust, jocks in jogging shorts and suntanned cheerleaders showing off their new curves? The girls bounced and laughed and danced in the air. The girls did slo-mo flips and gymnastics stunts, ballet leaps and jazz-dance moves—all except the girl we called Cujo, a stunted, breastless bitter thing—freckled, redheaded, bony as a shad. When she looked us over with her weird bulging eyes, we felt a burn in our guts, as though her gaze had lasered though skin and muscle to singe our organs, changing us from the inside out.

Cujo crept in the shade. Cujo mumbled foreign words—curses, we suspected, for she came from North Augusta, from Irish Travellers, people said. Her parents made dulcimers for a living and didn’t go to church. When Troy Hutto attempted a crash dive and fractured his femur, we spotted Cujo crouched under the trampoline, scratching in the dirt with a stick. When Tammy Day dislocated her elbow on the metal rim, we saw Cujo up in the honey locust, sprinkling leaf confetti onto the mat. When Chip Watts, King of the Air, piked off the tramp and landed on a brick that had not been there the day before, Cujo ate a fucking acorn (three separate kids witnessed her shelling it), hexing Chip, who spent the next three weeks earthbound and hobbling on a sprained ankle.

Though we whispered of banishing Cujo from the Watts property, we got the creepy feeling she could hear us plotting. What if she went apeshit and telekinetic, tossing our helpless bodies around like dolls? Truth told, the accidents could have been much worse, leaving us mangled and tragic, as our parents feared, so we let the freak lurk, let her stare with her weird gray eyes, pace and mutter and gaze up at the sky as though communicating with aliens beyond the clouds. We scrounged up good-luck charms to protect ourselves—rabbit feet, heirloom jewels, possum penile bones—and carried on with our business, always conscious of the darkness radiating from Cujo’s small spotted body.

The day Chip Watts stepped back on the trampoline, Cujo emerged from the woods with a garter snake wrapped around her left wrist. At first, we thought it was a plastic toy, but when she crept near, we saw it slithering, saw her whispering to the serpent, saw her snickering as though the reptile had hissed some irresistible joke. When Chip started with a fliffis, we held our breath, imagining him bashing his head on the T-junction, but he went right to a Randy and ended his routine with a perfect Miller Plus. Cujo be damned, he leapt from the tramp with an axe kick, falling right into the arms of Tammy Day, who rewarded him with a kiss.

As cicadas pulsed in the July heat, the kiss went on and on, making us tingle with lust-tinged shame. Though we should’ve slunk home, leaving the couple to their private passions, we couldn’t pull our eyes away from the storied quarterback and his head-cheerleader love, young and easy under the locust boughs.

That’s why nobody saw Cujo mount the tramp. That’s why nobody witnessed her first few stunts.

After the lovers parted and wiped their beslobbered mouths, we turned to the trampoline just in time to catch Cujo backflipping over a locust branch. Landing with ease, she launched an effortless quadriffi, a stunt that even Chip hadn’t mastered, each somersault more elegant than the last, her body lithe as a lemur’s, her face glowing with an uncanny beauty we’d never seen. When she straddle-jumped off the mat and landed in the grass, the loveliness drained from her body. She was Cujo again, speckled and smirking, her eyes too big for her head. She hightailed it toward the woods, leaving us shaken.

“What the hell?” said Tammy Day. “Where did she learn how to do that?”

Buy the Book

Hellions

Julia Elliott

Buy Book

Hellions

Julia Elliott

Buy this book from:

AmazonBarnes and NobleiBooksIndieBoundTarget

Like a rose blooming in time-lapse video, a boil sprouted on the tip of Tammy’s nose. As warm wind blew through the yard, pustulous acne erupted on the head cheerleader’s face.

“What?” Tammy scratched her nose.

Wendy Dyches handed her a compact. When Tammy opened the small round mirror and beheld her affliction, she wailed, crumpled, and wept. Refusing to speak to us, she shielded her face with her hands. “Maybe it’s the heat,” said Wendy. “Hives, scabies, or poison oak. Got to be some logical explanation.”

But we knew Cujo had cursed Tammy. Fearing some contagion, we backed away from the sobbing, zitty girl. Our sense of reality forever fucked, we gazed at the sky. Beholding convoluted clouds that evoked airbrushed paintings of the apocalypse, we half expected Jesus to whizz down in a flying saucer and summon the chosen among us. A gust of strong wind blustered through, along with ethereal yellow light, but a storm didn’t erupt. After Mrs. Watts called her boys in for supper, other kids drifted home, leaving just the two of us, Joe and Glen, sitting on the trampoline, discussing the day in hushed tones.

We decided we needed to see Cujo in her natural habitat, see if she had a trampoline in her backyard. We waited until dark and then set off through the woods, winding toward the place where Cujo’s dank split-level perched on a ravine above boggy land. When old Miss Emily died there in 1982, her family found possums nesting in the living room, mushrooms growing in damp shag carpet, the furniture velvety with mold. The house sat empty for five years before Cujo’s family moved in: her dulcimer-making parents, her three younger brothers who spoke a secret language that nobody but Cujo could understand.

When we crossed the creek, we spotted the house. The split-level, covered in wisteria, seemed to float in a bubble of light, a dwelling that existed outside of time. Clutching at exposed roots, we climbed up the eroded hill, at last reaching a chain-link fence. In the overgrown yard, Cujo’s small, pale dad strummed a dulcimer, his bald head glossy in the porch light. Cujo’s skinny mom emerged from the darkness, swaying in a white nightgown, standing a full head taller than Cujo’s father. The couple yodeled eerie harmonies, a song that made us forget why we had come.

“Kyarn!” yelled a child, jarring us from our trance.

Wielding spiked sticks, Cujo’s three brothers, none of them older than ten, rushed toward us—tiny wincing boys with dark hair, dressed in cutoff shorts.

“What’s the fuss?” cried Cujo’s dad.

“Sorry foons!” the boys yelled, climbing the chain-link fence.

We bolted, going the wrong way, running so far that we came out where Pocotaligo Road turned to dirt, a hundred dogs losing their shit at Country Canine Academy.

Though we never got used to Cujo’s stunts, we relaxed into the wonder of it all, the mid-July heat lulling us into a stupor, a fever dream of shrieking insects and eternally grumbling thunder. We learned to watch for the moment when Cujo lapsed into beauty, high in the air, her face surging with light, her hair a streak of fire, freckles glittering like flecks of copper on her skin. Perhaps the light that filtered through the honey locust tricked us. Perhaps ecstasy transformed the girl from within. Maybe distance and movement blurred her features as she catapulted and triple-flipped and performed grand jetés and cabrioles. Still, we braced ourselves for her landings. The second she touched earth, her ugliness surged back, and she hustled away, tittering and graceless. She kept to the margins, that weird zone between woods and yard, watching—waiting for her curses to take effect.

As long as we were respectful, and Cujo got her time in the air, her curses were harmless, a mild nuisance—like Tammy Day’s acne (which cleared up the next day), Marty Cope’s flatulence (nothing he hadn’t suffered before), and Crystal Goodings’s hiccups (which lasted until sunset)—curses so mild we wondered if we were imagining them. But then, one hot, gusty afternoon, a clutch of girls sniggered as Cujo lost her footing while mounting the tramp. Cujo jerked her head around and glared at the girls. Cujo murmured strange words. Nodding, clenching her fists, she stepped to the center of the mat. Dark clouds thickened above her as she warmed up with pikes and pucks. And then she went full-on whirling dervish, spinning and flipping so fast we couldn’t keep track of her tricks. As thunder boomed and lightning jagged, Cujo bounced higher than we’d ever seen her go, disappearing into the honey locust branches. And then she swan dove so quick we knew she’d break her skinny neck. But she touched down with a handstand and springboarded off the tramp, her skin flaring yellow the second she landed in the grass.

Cujo groaned and rolled her bloodshot eyes. Snot ran from her nose. Heaving, she staggered off into the woods.

As the downpour came, we made a run for the garage, relishing the dim light and the warm proximity of other bodies. Wendy Dyches sat on the chest freezer, chatting with her two best friends. But then she screeched and spat something into her hand. In her open palm, she displayed a molar with long bloody roots. Of the three girls who had laughed at Cujo, Wendy had been the boldest, releasing a cackle that had made her body shake. While Tina Platts had tittered into her fist, shy May Mood had merely snorted and smiled. Now Tina scratched her head, groaning as fistfuls of hair came loose from her scalp. We backed away from the afflicted girls, watching as bald spots appeared in Tina’s dark hairdo. We thought May might escape unscathed, but soon she was whimpering. She stared at us with puffy eyes, her lids festering with multiple styes.

“We’ve got to do something,” cried Hope Crews. “Can’t let that little freak dog us.”

A hush settled over us as we watched Hope, waiting for her to spit out teeth, lapse into baldness, or break out in leprous sores. Hope examined her slender arms and touched her cat-shaped face, testing for curses. When nothing happened, she strode to the center of the carport.

“Everybody has a weakness,” said Hope. “We’ve just got to figure out Cujo’s.”

Glen Cook stepped forth. In a quavering voice, he told the crowd the story of our excursion, how we’d ventured through the woods to Cujo’s home, finding no trampoline in her yard, only her yodeling parents and her younger brothers, who’d wielded homemade spears.

“But we didn’t see Cujo,” said Glen.

“You didn’t look hard enough,” said Hope. “She was probably floating right over you like a vampire child.”

After the other kids went home for supper, Hope lingered in the yard with us—Glen, Joe, and Crystal Gooding—setting up a secret rendezvous, vowing to solve the mystery of Cujo’s powers once and for all.

The muggy night smelled like boiled cabbage. The moon was a piddling thing, stars swarming above the field where the four of us—Glen, Hope, Crystal, and Joe—met up. We had flashlights and binoculars, knives and BB guns, orange pocket Bibles handed out by Gideons at Tillman Middle School. We took the shortcut through the woods, following Toadstone Creek down into the flood zone where Cujo’s split-level hovered above the ravine in an eerie orb of lamplight. As we climbed the hill, we heard bewitching singing, like something from beyond the moon. And then we saw her bouncing on a mini-tramp, her hair aflame around the pale shimmer of her face, her eyes flashing silver sparks. We couldn’t bring ourselves to call her Cujo in this form, the name Marty Cope had given her on the Tillman playground the time she nabbed our football—the time we cornered her behind the jungle gym. Snarling, she’d bared her crooked teeth. And Marty had forever branded her with the name of a murderous, rabid dog.

This creature that bounced slowly, performing languid stunts, was not Cujo. This being that sang in a timeless voice was not Cujo. Stunned, watching the girl hover in the rich night air, we couldn’t recall her real name. Though we’d seen flickers of her beauty in the Watts backyard, she’d moved too quickly there for us to focus, to suck in her loveliness with our eyes and fill our bodies with it, charging our very marrow with light.

Who knows how long we stood there, mouths slack, lulled by her music, yoked together by the inexplicable vision before us? When the brothers came yowling out into the yard, their sister ceased to sing, but still she bounced, luminous, sustaining states of unnatural buoyancy. The brothers whirled around her, lashing at her ankles with their spears. The brothers lunged and gibbered. They pulled fistfuls of powder from pouches strapped to their belts and flung it into their sister’s face, causing her to sneeze, stumble, and fall into the grass. When she stood up, her skin crinkled, and her lovely lean form became bony and crooked. Her hair turned gray and thin.

“Hag!” the brothers yowled, dancing around a tiny crone.

The crone’s hair floated away like ash, leaving her bald, her scalp scaly and faintly blue. She spat out teeth. She shrank several inches. We feared she’d shrivel to skin and bones. But then, in a blink, she was Cujo again, freckled and pubescent, snarling and cursing. The brothers climbed the fence and fled to the woods, running right past us, out to a flat stump, where they began pounding objects with rocks.

We showed up the next afternoon as the others did, stood around watching Chip do warm-up jumps. Everybody seemed restless, disturbed by the absence of Wendy, Tina, and May, watching the woods for the appearance of Cujo.

Wendy, kids whispered, had been rushed to Dr. Burroughs, a dentist who assured her parents that X-rays revealed a mouthful of healthy teeth, though it was crucial that the girl be fitted with an implant to replace the missing molar. Doctor Pendarvis had informed May’s parents that though her styes were unusually numerous, they fell within the range of normality and would take at least a week to heal. Tina’s dermatologist, who babbled vaguely of hormonal shifts, teen stress, junk food, and trichotillomania, could not predict when her hair might grow back, though he assured the girl’s parents that her follicles were not dead.

At the height of afternoon, cicadas pulsing in the muggy air, Cujo came staggering from the woods. Bent and scowling, she looked even punier than she usually did. She had gray streaks in her hair, bags under her eyes, lines around her mouth. Mumbling to herself, she lurked in the shade of the honey locust, glaring at Tammy Day, who bounced idly on the trampoline, attempting the occasional straddle-jump. When Tammy finally saw Cujo skulking in the shadows, she hurried to the edge of the mat, climbed down carefully, and slipped behind her posse of girlfriends.

Cujo climbed the tramp, muttering as she scrambled over the edge. She stood wincing in the circle of blackness, a small, scrunched creature, her eyes squinting in concentration. We didn’t realize we were holding our breath until she started jumping, two-foot tucks that any four-year-old could manage, not her usual starting fare. When she pulled off a pike jump, we relaxed, waiting for her to launch a backflip and then leap into her otherworldly form. But Cujo fell flat on her bony ass—a spot drop, we thought, even though she never messed with such trifling stunts. Cujo crumpled and moaned. Grunting, she heaved herself up, tottered to the trampoline’s edge, and tumbled into the long grass.

As the girl writhed and whimpered on the ground, Tammy Day sashayed forth, walking with the same hip-sway her beautician mother had perfected. With a flourish, Tammy kicked Cujo in the ribs, making the girl go limp—playing possum, we hoped.

“That’s what you get for messing with Tammy Day,” said Tammy. “My granny told me to tell you that, you freakish devil child.” Tammy stood triumphant over the fallen girl, her glorious hairdo, shellacked with Aqua Net, glinting in the sun. We pictured Tammy’s granny hunched in the back room of Delilah’s Salon, her jet-black beehive sitting crooked on her skull. The old woman, who’d started Delilah’s back in the fifties, now told futures by flipping through a Bible at random, pronouncing fates in hifalutin King James while Tammy’s mom did hair.

We wondered if the old lady had powers, wondered if Cujo suffered from a double curse. When Tammy’s friends crowded in, we feared they’d maul Cujo, but the girls just stood behind Tammy, glaring and radiating hatred.

At last, Cujo lifted her head, gazing at the long stretch between herself and the woods. At last, she rose, crooked and swaying. As she stumbled away, we stood in silence, listening to her bones creak, sighing when she disappeared into the trees.

The next day, when Cujo failed to creep from the woods at her usual time, Tammy Day stepped simpering onto the trampoline. She did a double-back somi, landing in pirouette pose. Laughing with full-throated ease, she twirled and swished, her limbs golden, her feathered hair shining with blond highlights. Chip Watts scrambled onto the mat, slipped his arm around her waist, and gracefully lowered her into a dip. For hours the couple cavorted, pawing at each other as they leapt and flipped, leaning in for kisses, showing off their perfect bods. They were King and Queen of Summer again, showing off in the air, leaving the rest of us earthbound. The fools among us cheered them on, leering slavishly in the heat, charged with vicarious glory.

Enveloped smugly within a bubble of secret knowledge, the four of us—Glen, Hope, Crystal, and Joe—slunk off to the shade. We were the only ones who’d glimpsed the heights of Cujo’s beauty and the depths of her hideousness, her vulnerability to the people who knew her best, her abrupt morphing into miniature hagdom. Speaking in low tones, we wondered what powers she possessed. Her rapid balding, tooth loss, and bodily shrinkage embodied the horrors of annihilation. When her freckled teen form surged back, it had seemed extra juicy and potent, almost pretty by comparison—the very essence of human life.

When we finally got our turns on the trampoline, we felt strangely deflated, as though our stunts had no meaning without Cujo there. Soon it started drizzling, as though the sun had eyes only for Tammy and Chip, and the Watts boys’ mom declared the trampoline too wet for jumping. The four of us drifted toward the woods again. We found the footpath Cujo took through the forest, a trail so light it might’ve been made by bobcats. We wove deeper into the trees than we’d ever gone, finding a dim swampy floodplain loud with frogs. Vines swaddled the trees. In a clearing, cabbage-like plants clustered around a pool of water. We stood around the tiny pond, watching weeds waver from obscure currents. Speaking again of Cujo, we wondered if we could help her somehow, wondered if we could find her brothers and take their magic pouches away. We all admitted we hated Chip and Tammy, that we wanted to see them curse-stricken and staggering in the July heat, bereft of beauty, unable to escape gravity’s grip.

A mourning dove called. A tree frog barked.

And then we saw her—the girl, pale as a sand bass, sunk in the pool’s depths.

“Drowned,” Glen rasped.

As though awakened, the girl whooshed up through the water in a rage, clawing at air, screaming words we didn’t understand. Her eyes looked filmy, and she didn’t seem to see us as she staggered down a forest path, bumping into trees. Though we tailed her through the woods, we couldn’t keep up. Soon her house appeared, perched above the gulley, and we climbed up the eroded terrain. But when we reached the top, the fence was gone. We found no split-level house—only a bald hill littered with broken bricks.

“Cujo,” we called, ashamed we didn’t know the girl’s true name, something lovely and old-fashioned, we guessed, like Guinevere or Christabel.

“The Maiden,” whispered Glen, and the name stuck.

The four of us—Glen, Hope, Crystal, and Joe—stopped hanging out by the trampoline. We spent our afternoons searching for the Maiden, vowing we’d vanquish her brothers and release her from their spell. We mused as always on the riddle of her address—level when approached from the front, perched on a hill when glimpsed from the deepest part of the swamp. When climbing from the south side of the woods, we always found a scraggly hill. When climbing from the north side, we sometimes found her house, blocked off by a chain-link fence, though we never saw a single soul in the yard.

One long hot Saturday, we walked down Wisteria Way, the crumbling asphalt road that led to the vine-smothered split-level where Miss Emily had died in 1982. We found no cars in the driveway, no action in the overgrown yard. Though we banged the brass knocker and pounded the peeling front door with our fists, nobody answered. Nobody stirred inside the house. When we slipped into the yard from the side, we found ourselves in the woods again, winding down toward swampy land, no house in sight.

“Lost,” mused Hope, as we walked in circles, the soles of our sneakers caked with black mud. That’s when Glen and Crystal found the pool again, concealed by a scrim of dead leaves that we brushed away with our hands, marveling at the coldness of the water. Hunkering around the tiny pond, we gazed into its dark depths, detecting wavering weeds and tiny silver minnows. The forest breathed around us, frogs and insects throbbing.

We gasped when we spotted her—the Maiden sleeping at the bottom of the pool, pale as a ghost salamander, her skin translucent and faintly aglow. She had not been there two seconds before—the girl we’d seen bouncing on the mini-tramp, the girl whose singing made us stare too long at the moon. Perhaps she’d floated up from deeper depths. Perhaps she glowed sometimes, and other times stayed dark. Maybe she flickered in and out of our plane of existence, surging in from another dimension, the fourth or the fifth—we could never remember the differences between the two. We discussed these theories later that night. But in the woods, we stayed quiet, focusing on the wonder of her face. We didn’t want to wake her again, send her blind and reeling through the swamp.

When the woods went dark and chuck-will’s-widows called, a light flashed on at the top of the hill. We again saw Cujo’s split-level, which seemed to float in the trees. Returning our gaze to the pool, we found only darkness—no gleaming Maiden sleeping in the silt. We took a long foot trail up the other side of the hill, catching glimpses of the old brick house, but we couldn’t access it from the woods, no matter how many paths we tried. Exhausted, we found ourselves on Pocotaligo Road again, farther away than before, out near the Pentecostal Holiness Church.

July was almost over, and we stalked the woods with desperate ferocity, sweating in the muggy heat, longing for the feel of cool water, pining for the sight of the celestial Maiden submerged in the depths of an uncanny pool. Doubting our vision, we compared notes, bickering about trivial details—the length of her hair, the shape of her lips, the intensity of her luminescence.

“Maybe it’s all just tricks,” said Glen. “Her family a bunch of shifty travelers.”

Disgusted by this thought, we took the shortest path up the hill, discovering, once more, eroded terrain and scattered bricks.

“Sick and tired of this,” hissed Crystal, kicking a brick.

We were sick and tired of our shit town. Sick and tired of Chip and Tammy lording it over everybody. Sick and tired of the endless summer day breathing down our necks like a panting dog. The Maiden had given us a glimpse of otherworldly possibilities, and now we couldn’t find her.

“I say we sneak in,” said Crystal.

“You mean break in,” said Hope.

“Semantics,” said Crystal, a vocabulary word the rest of us didn’t know. We didn’t ask what semantics meant. We followed Crystal down the path to Wisteria Way. Finding no cars in the driveway, we climbed the familiar front stoop with its lichen-covered brick and rusted screen door. We knocked and waited, listening for the rustle of humans inside. And then Crystal tried the knob.

“Unlocked,” she whispered.

We crept into a shadowy living room decorated with orange shag carpet and lime brocade drapes. A white baby grand piano stood in a far corner, surrounded by piles of books. The house smelled of mold and rat piss, the windows sealed with electrical tape. On the wall was an oil painting of Miss Emily’s only son, immortalized in his pug-nosed, towheaded toddler form, the boy who’d grown up to become a playboy podiatrist in Atlanta. We found boxes of dishes in the kitchen, a naked mattress in the master bedroom, a plastic stool in a stained pink bathtub. We tested the switches for electricity, the faucets for running water, finding neither.

“She doesn’t live here,” said Glen, his voice hoarse with despair.

We exited by the sliding-glass door, finding ourselves in the overgrown backyard we’d viewed from the other side of the chain-link fence. On a rusted iron garden table, we found a dulcimer, rain-warped and lacking strings.

“Miss Emily,” Crystal reminded us, “was a music teacher.”

“Right,” said Hope. “But Cujo’s parents make dulcimers. We saw them singing that night.”

This dulcimer had been rotting for at least a decade—its wood splintery, furred with yellow fungus.

“Wishful thinking,” said Crystal, striding off toward the gate that led to the road. “I’m done.”

The rest of us climbed the fence and descended into forest gloom. We stumbled around the woods looking for the pool, knowing we wouldn’t find it.

Over the next few weeks, the Maiden became a hazy memory, and we wondered if we’d been fooled by an illusion, a mannequin or doll immersed in water, Cujo concealed in a pile of leaves, rising so fast she tricked us. We wondered if her trampoline stunts seemed spectacular only because we didn’t expect much from the strange, ugly girl. Every time Glen uttered the words the Maiden, his voice all whiny and wistful, Crystal sneered: “You mean Cujo?”

The last Saturday before school started, we went to the Watts place for their annual catfish stew party, keeping our distance from the drunken adults, who gabbed about their boring lives as tall, potbellied Mr. Watts manned his propane cooker, scarlet-faced, stirring an eighty-quart aluminum pot that bubbled with his pungent specialty: catfish nibbles and potatoes simmered in tomato sauce and Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom, spiced with generous splashes of Worcestershire and Texas Pete, flavored with fried hog jowl and served over rice. Mr. Watts had spent the summer catching enormous bottom-feeding catfish, stashing them in his chest freezer, and now the big day was upon us, a scorcher to beat all scorchers. The air smelled of pond funk and burnt Crisco. The birds sounded hoarse, and dying cicadas buzzed in the parched yellow grass.

The four of us joined the teens that thronged around the trampoline, watching the lesser jocks and cheerleaders perform the prelude to Chip and Tammy’s new routine, a number they’d been practicing for weeks. Kids whispered that they’d perform a strip tease in the air. Kids whispered that they’d consulted the Kama Sutra, that they’d mime intricate sex acts from heights of twenty feet.

Heshers and skags who’d already graduated rolled up to the spectacle in Firebird Trans Ams and Camaro V8s—long-haired dudes who blew their cash on cars, bad boys accompanied by underage girls in acid-washed miniskirts. This crowd pulled Millers from mini-coolers and smoked Marlboro Reds right out in the open, getting glares from Mrs. Watts, who was up to her elbows in hush-puppy dough.

Teens sipped beer from Solo cups. Teens slipped behind the shed to smoke and make out. Heat-stunned and tipsy, teens ate fishy slop from paper plates that soon turned grease-soaked and floppy. We all watched Chip and Tammy hold court under a beach umbrella, at ease with the world, as though they’d never tasted Cujo’s curses, as though they’d never been bested and never would be. Summer’s royals lolling in lounge chairs, stretching their sun-bronzed limbs, they’d reign at Swamp Fox High just as they had at Tillman Middle.

It was half past two o’clock, and Chip and Tammy lingered over their dessert, feeding each other banana pudding, toying with our expectations, chilling as though they hadn’t been dreaming of the glory of this day. By the time they approached the trampoline, there was a dangerous charge in the air, too many kids crowding in, older heshers mingling with teens, drunk adults screeching cheers from the patio. The sky looked green-tinged, the clouds jaundiced. Weed smoke wafted from obscure sources. Somewhere in the distance, a chain saw started up.

That’s when Cujo skittered out from the woods, so fast she blurred, so fast that nobody saw her except us—Glen, Hope, Crystal, and Joe. Everybody else had their eyes on Chip and Tammy, who stood frozen in the middle of the trampoline as the opening keyboard riff from Europe’s “The Final Countdown” blared from a boom box. Cujo scurried behind the azalea hedge. When the drums kicked in, Chip and Tammy popped into action with a triffis for each of them, performed simultaneously, landing with doggy drops. When they rebounded with Axl Rose snake-dance moves, Cujo came screaming from the shrubs—freaky teeth bared, fists clenched, thin red hair streaming. From a distance of six feet, she leapt onto the tramp, popped Chip in the neck with a front kick and Tammy in the face with a side, knocking them both off the mat, sending them rolling into the overgrown grass.

The collective murmur of the entranced crowd resembled a distant rumble of thunder. Cujo stood still, psyching herself up for her first jump—her eyes closed, her goblin face scrunched in concentration. For a second her homeliness seemed to condense, as though to fuel the marvelous stunts to come. And then she was airborne, her body curled in the turns of a perfect quadriffi, soaring higher with each flip. By the time she reached her fourth salto, she’d shaken off her earthly form, morphing into a being of movement and light.

She was the Maiden, lunar-skinned and silver-eyed, her hair a flurry of flames. The adults went stiff and silent on the patio, frozen with beer cans in their hands, their mouths open mid-sentence. Chip and Tammy sat up in the grass, dull-eyed, their faces slack. The other kids, who’d never really seen the Maiden, stood stunned and panting in the heat. The heshers lost their cool-dude vibes as wonder overtook them.

The Maiden touched down and sprang into a double quadriffi, spiraling past the highest branches of the honey locust. And then she swan dove, a fiery streak plummeting. Just when we thought she’d crash, she veered upward and hovered above the trampoline, three sets of dragonfly wings fluttering on her back. Except for the two glossy orbs that spun in her eye sockets, her face was blank—no mouth, no nose. But then a fang-fringed orifice opened near her chin. The sounds of flutes and chimes floated out, high and sharp in the bright air.

That’s when Chip and Tammy stood up and started twitching. At first, we thought the Maiden had cursed them with run-of-the mill seizures. But then we noticed they jerked in sync, contracting into terrifying rigidity and then going limp, their faces slack and expressionless. With each move, Chip and Tammy lapsed into intensifying ugliness—gargoyle-faced and scaly-skinned, bat-eared and dog-snouted. Their hair was greasy and matted. Their eyes glistered a sick snot green. Long gray tongues flopped from their mouths. Though we’d never been able to see it before, this repulsiveness had always been inside them.

The other teens stood spellbound, unable to speak. The adults remained frozen on the patio, all except Mr. Watts, who, hexed by Cujo, sprang into action, amping the heat on his propane cooker and whistling an intricate tune beyond his normal capabilities. As Chip and Tammy danced spastically around the yard, Mr. Watts added items to his stew, throwing in whatever was at hand—beer cans, Solo cups, flip-flops, and sunglasses—filling the air with the apocalyptic stench of molten plastic.

We four—Glen, Hope, Crystal, and Joe—were the only ones the Maiden hadn’t hexed, the only people who served as true witnesses to whatever the hell was going on. The Maiden was an angel of death, we hoped, there to reveal dark truths and announce the day of reckoning—insect plagues, blood rain, meteor showers, and wormwood-tainted water. We scanned the clouds for swarms of angels, pop-eyed with fury, shrieking at decibels that would bust our eardrums. We hoped the Maiden would sweep us up into some frenzy, whisk us away to an otherworldly locale where she, reverted to her comely form, would crown us as chosen. After all, we were the ones who understood her true beauty, the ones who’d searched for her in the forest, the ones who’d found her sleeping in the bottom of the pool. We were the ones who’d plotted to thwart her brothers, who seemed hell-bent on destroying her.

But the sky didn’t erupt into apocalyptic havoc. Mr. Watts sat down in his lawn chair, by all appearances a normal man exhausted from outdoor cooking. He dozed off, his head slumped forward. Chip and Tammy fell to their knees, ecstatic looks on their hideous faces. The other teens turned away from the Maiden. Only the four of us—Glen, Hope, Crystal, and Joe—kept our eyes locked on the terrifying but eerily beautiful image of her true form—wings, whirling eyes, and glittering, exquisite teeth. We secretly longed to be devoured, chewed up, and incorporated into the body of the Maiden—anything to escape the future that awaited us in this shit town. How could we return to our paltry lives after witnessing her glory? How could we face the indignities that awaited us at Swamp Fox High, where monsters like Chip and Tammy reigned?

When a hundred smoke-blue songbirds stirred in the honey locust and started twittering, we four reached for the Maiden, extending our arms like toddlers. But the Maiden didn’t pick us up. She whirred in circles, up past the highest branches, and darted off into infinite space. Sighing, we hoped she’d return to gravity’s clutch, touching down upon the bounce mat as she always did, springing into the grass, lapsing back into flesh and blood. But the Maiden shrank to a fleck and passed into distant clouds, twinkling with pink light as she vanished from our world.

Copyright © 2025 by Julia Elliott. Reprinted with permission from Tin House.

The post Read an Excerpt From <i>Hellions</i> by Julia Elliott appeared first on Reactor.