www.theblaze.com

I was a 'problem student' — until all-male Catholic school let me be a boy

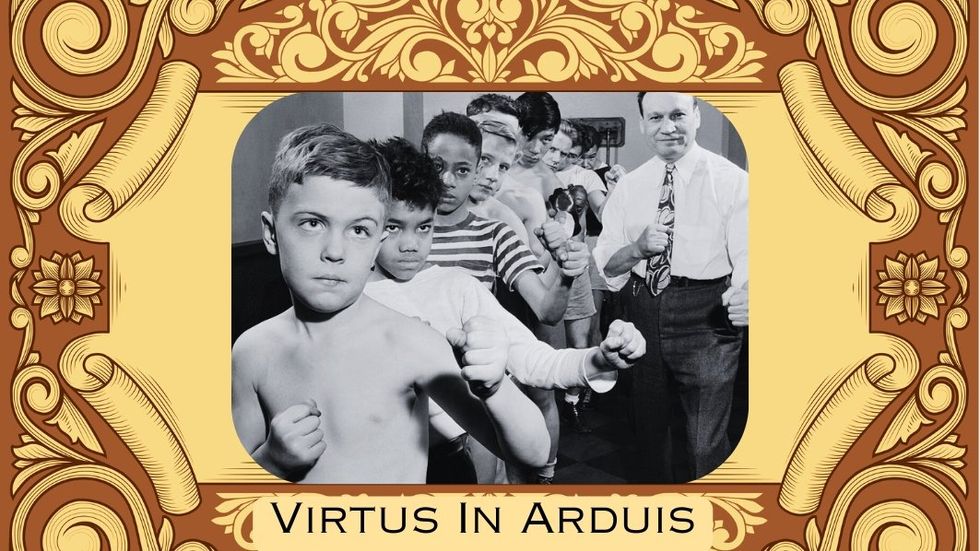

I have an old friend who owns a lefty/progressive bookstore here in Portland. I was visiting him recently when he told me his son is entering high school next year. “He wants to go to Central Catholic,” he told me, with some concern. “His mother and I were shocked. I know you went to a Catholic high school. Why would he want to go there?”I thought about this and quickly came to the obvious conclusion. His son is conservative. At least in terms of what kind of school he wants to go to.It wasn’t like public school, where you were required to show respect to your teachers. These guys commanded respect. They were serious people.All of the public schools in Portland are very progressive, very activist. So much so that they frequently veer off into "Portlandia" levels of absurdity.My friend’s son probably understands that attending Central Catholic is his best chance to have a semi-normal, traditional high school experience.I wasn’t sure how to break this news to my friend, so I mumbled something about Catholic schools having more structure and better academics and that “it might look better on his college applications.”I was trying to let him down easy. But I understood the reasoning of his son. When I was his age, I did the same thing.The tolerance trapMy middle school experience was also at a Portland public school. Even though that was decades ago, it was very much the same as it is today.My family lived in an affluent district, so my school was full of smart, well-behaved, upper-middle-class kids. The teachers were some of the best in the city. The school was so highly rated that they bused in disadvantaged black kids from across town — to share the wealth, so to speak.I loved this school. It had nice kids. Pretty girls. Permissive teachers. Lots of sports. We even had our own ski bus.The only problem: I was a small, excitable, hyperactive kid. I tended to be a bit of a smart aleck and a class clown. I had already been held back a grade in elementary school because of my “immaturity.”Of course, the teachers at my new school were tolerant of my behavior at first. That’s the kind of school it was. Very inclusive and forward-thinking in its educational philosophy. They were slow to punish and dealt with each child as an individual. We were “people,” not just students.So how did I respond to this tolerant and accepting environment?I became an even bigger smart aleck! I was disruptive. I got in trouble. I got in fights.RELATED: Giving entrepreneurs an 'EXIT' from cancel culture Minnesota Historical Society/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty ImagesProblem studentI was not aware that I was a problem student. I liked my classes. I got good grades. I was popular and even had a girlfriend.But the teachers thought otherwise, so much so that halfway through eighth grade, they dragged me and both my parents into a special after-school conference to express their disapproval.Every teacher and administrator in the school took turns describing my terrible behavior. I ran in the hallways. I threw someone’s pencil out the window. I picked up a girl and threatened to carry her into the boys' bathroom.I was surprised by how upset everyone was. I had no idea I was causing so much trouble. I thought I was being funny. I thought these teachers liked me!Going Jesuit That summer, with high school looming before me, my parents and I considered my options.I could go to the public high school, where I might get into more trouble. Or I could go to Jesuit, an all-boys Catholic high school not far from where we lived. All I knew about Jesuit was that it was strict. And all boys. And priests taught you.My family was not religious. And neither was I. But somehow it was decided that Jesuit was the better choice.Years later, I asked my mother, “When did you decide to send me to Jesuit?”“We didn’t decide,” she replied. “You wanted to go.”Peace through hierarchyI have vivid memories of my first day of school there. I was overwhelmed by the rowdy atmosphere in the hallways between classes. The roughness of it. The boy-ness of it.There was a distinct male energy to the place and a kind of underlying threat of violence. Not actual violence. Nobody was going to hurt you. But there was a definite hierarchy that existed among the students. And it wasn’t negotiable.As a freshman, you were at the bottom of the pecking order. This was not necessarily unfair, as everyone at the school had once been a freshman. So everyone had gone through the same process.For me, this hierarchical structure had a calming effect. There was nothing you could do about it. And it helped you bond with the other freshmen.All of us frosh suffered our various humiliations together. It was all very Classic American High School circa 1955. It was timeless in a way. And though the public school types might have considered it uncool or retrograde, I had no problem with it.Boys to menAnother thing that struck me during those first days: the seriousness with which the school operated.There were rules, and you followed them. The lay teachers were men. The priests were men. The administrators were (mostly) men. The principal was a man.It wasn’t like public school, where you were required to show respect to your teachers. These guys commanded respect. They were serious people. One of our football coaches had briefly been a San Francisco 49er. My geometry teacher had flown helicopters in Vietnam.Measurable distanceMy social life was what suffered the most during my first year at Jesuit. The only girls we officially socialized with were the girls from the two all-girls Catholic schools.There were dances and other activities to bring us together. These girls were not as slick and sophisticated as the girls at public school. Some of them appeared to be right off the farm. So there were often awkward encounters.But it was still fun. And there was an innocence to it. And it was often hilarious. Like the nuns really did come around to check on you and make sure a measurable distance was maintained between the boys and the girls while slow dancing in the dark.And best of all: If you embarrassed yourself with a girl on Friday night, she wouldn’t be sitting next to you at school on Monday morning.Football, not feelingsThe schoolwork was hard at Jesuit, but at the freshman level it was basic and rudimentary. You realized the teachers were not so much teaching you in an overly intellectual way. They were teaching you how to focus and concentrate and organize your time.That was the real genius of the school: It took into account the reality of teenage boys. Oh, you have a lot of energy? You can’t sit still? You’re feeling aggressive?Jesuit had sports for that. We had football. We had a weight room. The teachers and administrators didn’t worry about your feelings. Their strategy was to provide various ways for you to burn that adolescent energy and then keep you moving toward adulthood, where most of your problems would work themselves out on their own.Refuge for the rambunctious Catholic school was a perfect place for a kid like me. And yes, I remained a troublemaker. A class clown. An instigator of various escapades. But everybody expected that. The whole place was designed to withstand the rambunctious and destructive nature of teenage boys, to reroute that energy and put it to good use.As it turned out, I never got in serious trouble there. Not for four years. No fights. No conferences with my parents. And since there were no girls to pick up and carry around, I never did that either.No school like the old school So I hope my friend’s son enjoys Central Catholic. It’s co-ed now, as is Jesuit, my old school. All-boys schools, it seems, have ceased to exist. So it’s probably a softer, gentler Catholic school than the version I saw.But I’m sure it will still be a more uplifting experience for him than public school, where male energy is seen as toxic and boys are put on psych meds if they show any form of “willfulness.”And what about “all-boys schools”? The concept seems unimaginable in our current times.But I bet if they brought them back, a lot of boys would eagerly enroll. Even if they had to talk their parents into it.