www.dailysignal.com

Earle-Sears Slams Spanberger for Having ‘Sold Out Virginians’ by Taking Cash From Environmental Groups

Virginia Republican gubernatorial candidate Lt. Gov. Winsome Earle-Sears attacked her Democrat opponent, Abigail Spanberger, for prioritizing the climate policies of environmental groups that contributed to her campaign, rather than an all-of-the-above energy plan.

“Abigail Spanberger has sold out Virginians to the highest bidder,” Peyton Vogel, Earle-Sears’ press secretary, told The Daily Signal in a statement Tuesday. “She’s taken millions from green special interests who want to force Virginia back into [the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative] and drive up energy costs for working families.”

“Winsome Earle-Sears can’t be bought,” Vogel added. “She stands for Virginia families, for an all-of-the-above affordable energy approach, and for doing what’s right rather than what’s politically convenient.”

Spanberger is running on lowering costs for Virginians, promising last month that she “will be laser-focused on bringing costs down for families.”

Yet she advocates policies that would arguably increase prices, such as returning to the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative and achieving the goals of the Virginia Clean Economy Act, a 2020 law that requires Virginia’s utility companies—Dominion Energy and Appalachian Power Company—to shift to renewable energy by 2045 (for Dominion) and 2050 (for Appalachian).

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, an inter-state agreement, charges power plants for emissions and uses the money to prop up renewable energy. Gov. Glenn Youngkin, a Republican, attempted to exit the initiative, calling it a “hidden tax” on electricity. Virginia’s withdrawal remains in limbo after judge blocked it. The administration has a stay, allowing Spanberger has pledged to rejoin it.

Constricting Choices

“All these policies will do is constrict our energy choices while having no meaningful impact on the climate,” Kevin Dayaratna, director of Heritage’s Center for Data Analysis, told The Daily Signal.

He said the Center for Data Analysis “looked at these policies at the federal level during the Biden administration using the government’s own models and found the result would be over $7 trillion in lost GDP over a 20-year time horizon, with less than two-tenths of one degree Celsius impact by the end of the century.”

“Spanberger would apply these inane policies to Virginians while having an even more trifling impact on the climate,” Dayaratna added.

Center of the American Experiment economists estimated the Virginia Clean Economy Act will cost an extra $3,500 per customer by 2045. After the law’s passage, Virginia’s electricity imports from out of state rose from 18% in 2020 to 40% in 2024.

“Spanberger says she is committed to wind, solar, and grid batteries,” Steve Milloy, a senior fellow at the Energy & Environment Legal Institute, told The Daily Signal. “This means she is committed to ever-higher electricity prices.”

“In Congress, she voted for the inflationary Green New Scam and generally supported President Joe Biden’s policies that sent gasoline prices through the roof,” Milloy added.

Follow the Money

The Virginia League of Conservation Voters gave Spanberger for Governor $1.38 million, and the Clean Virginia Fund contributed $700,000, according to the Virginia Public Access Project.

“Spanberger is the only candidate in this race who will prioritize Virginians over big corporations by ensuring we meet the moment with clean, affordable energy and work to make electricity more affordable for Virginians instead of doubling down on dirty, expensive energy sources that line corporate polluter pockets by keeping our bills high,” Lee Francis, a spokesman for the Virginia League of Conservation Voters, told The Daily Signal.

Francis said the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative “has a proven track record of lowering energy costs by incentivizing clean, and affordable energy sources over volatile coal and gas.”

He claimed the programs receiving initiative funds “have a high return on investment,” preparing communities to face flooding and cutting energy costs “with programs that weatherize homes and make them more efficient.”

He claimed that “increased fuel costs and infrastructure costs related to transmission and distribution, mostly to feed large energy-hungry data centers, are the largest drivers of bill increases in Virginia—not clean energy and not the [Virginia Clean Economy Act].”

Clean Virginia, meanwhile, attacks the Old Dominion’s public utility companies, aiming to fight for “clean government and clean energy by fighting utility monopoly corruption.”

“Abigail Spanberger’s plan for energy abundance focuses on investing in clean technologies, the only resources that can come online quickly, improve reliability, and lower costs for consumers,” Clean Virginia Executive Director Brennan Gilmore told The Daily Signal. “Clean Virginia supports her leadership to build an affordable, reliable and forward-looking energy system.”

RGGI Negatives

Glenn Davis, director of the Virginia Department of Energy under Youngkin, told The Daily Signal that RGGI cost Virginians $828 million, “every dollar of which was passed on to Virginians in their energy bills.”

He said other states use RGGI funds to offset ratepayers’ energy bills, since the program increases costs for consumers, but Virginia Democrats used the money to fund other projects, such as the flooding preparation Francis mentioned.

Davis also criticized the Virginia Clean Economy Act. The act requires companies like Dominion to buy renewable energy credits if they can’t produce enough renewable energy themselves. Earlier this year, Dominion estimated it would have to buy $5.5 billion of renewable energy credits in the next ten years in order to make benchmarks.

Dominion Energy Responds

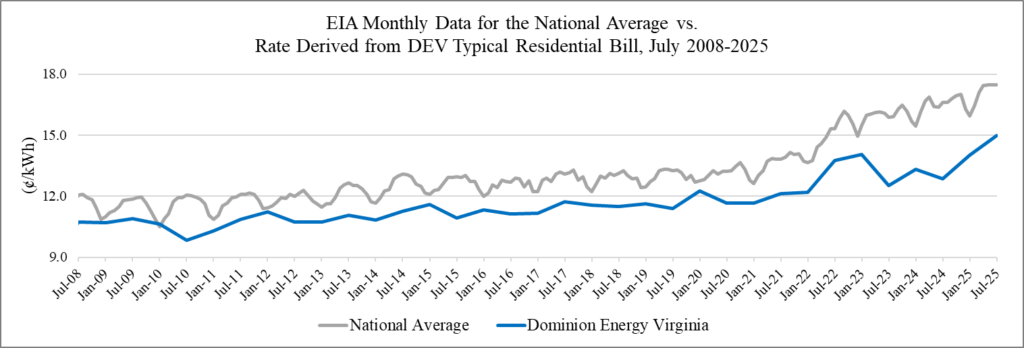

“For nearly 20 years, our electricity prices have remained below the national average,” Aaron Ruby, a spokesman for Dominion Energy, told The Daily Signal. “Our prices are currently 8% below the national average, and we expect that will continue in the coming years.”

Ruby said Dominion proposed a price increase earlier this year “due to significant increases in the cost of fuel for our power plants and for equipment such as utility poles, wires, cables, and transformers.” These inflationary pressures have impacted the entire economy.

He also referenced a recent Washington Post article highlighting the various reasons energy costs are increasing—and noting that the proliferation of data centers plays only a very small role in price hikes.

Ruby countered Clean Virginia’s attacks by saying Dominion participates in the political process “on behalf of our customers and employees.” He said the company contributes to candidates of both parties “in support of bipartisan, common sense energy policy.”

Karen Wissing, a communications consultant at Appalachian Power Company, also noted that her company “faces higher interest rates and inflation, which have increased and are continuing to increase the cost of generating and delivering power.”

“The company recognizes the need to provide safe, affordable electricity and works every day to keep bills as low as possible,” Wissing added. She noted that Virginian customers can expect an approximately $10 decrease in fuel costs on Nov. 1, and she referenced the company’s request with the Virginia State Corporate Commission, which could result in additional savings of approximately $11.44.

Wissing also mentioned that Appalachian offers energy efficiency programs.

The Spanberger campaign did not respond to The Daily Signal’s request for comment.

The post Earle-Sears Slams Spanberger for Having ‘Sold Out Virginians’ by Taking Cash From Environmental Groups appeared first on The Daily Signal.