www.dailywire.com

RFK Jr. Shakes Up Childhood Vax Schedule With Hep B Decision

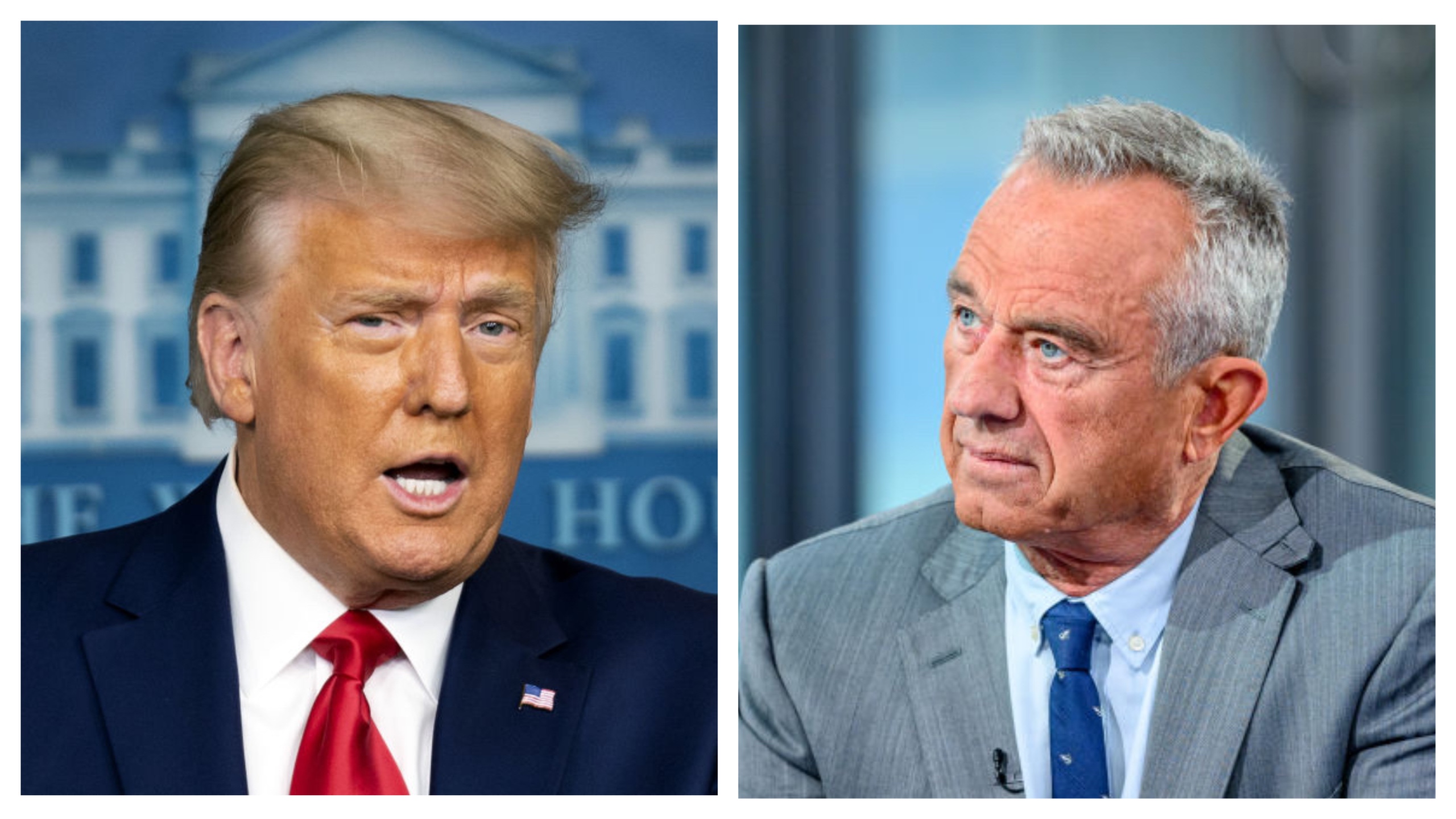

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) vaccine panel recommended this week that the hepatitis B immunization should not be given to all babies immediately after birth. The decision was fully supported by President Donald Trump, who then took the issue one step further, signing a memorandum to “fast track” a full evaluation of the childhood vaccine schedule.

The decision from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or ACIP, marks a major shift, changing up standard practice in the United States for some 30 years.

In an 8-3 vote, the panel recommended the hepatitis B vaccine only be given at birth for infants whose mothers test positive for the virus, or whose status is unknown. If a mother has a negative hepatitis B status, she should speak to her doctor about getting the first dose of the vaccination at birth.

Traditionally, the vaccine is given in three separate doses. The ACIP panel decided that some children do not need a third dose, and recommended testing children’s antibody levels before determining if they need follow-up doses.

50% off DailyWire+ annual memberships will not return for another year, so don’t miss this deal! Join now at DailyWire.com/cyberweek.

On Friday, Trump posted on Truth Social that the decision from ACIP is “very good” and criticized the general vaccine schedule for children.

“[T]he CDC Vaccine Committee made a very good decision to END their Hepatitis B Vaccine Recommendation for babies, the vast majority of whom are at NO RISK of Hepatitis B, a disease that is mostly transmitted sexually, or through dirty needles,” the president wrote.

“The American Childhood Vaccine Schedule long required 72 ‘jabs,’ for perfectly healthy babies, far more than any other Country in the World, and far more than is necessary,” Trump continued. “In fact, it is ridiculous! Many parents and scientists have been questioning the efficacy of this ‘schedule,’ as have I!”

Trump then announced that he signed a “Presidential Memorandum directing the Department of Health and Human Services to ‘FAST TRACK’ a comprehensive evaluation of Vaccine Schedules from other Countries around the World, and better align the U.S. Vaccine Schedule, so it is finally rooted in the Gold Standard of Science and COMMON SENSE!”

“I am fully confident Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., and the CDC, will get this done, quickly and correctly, for our Nation’s Children,” the president added. “Thank you for your attention to this matter. MAHA!”

Truth Social

In addition to other notable changes, Kennedy’s Health and Human Services department has so far modified COVID vaccine recommendations, advised that young babies get vaccinated against chickenpox separately, and opened the door to exploring a connection between vaccines and autism.

Related: Vax Panel Takes On COVID, Hep B, And MMRV Vaccines. Here’s What They Decided.