www.thecollector.com

The Tumultuous Life of Maria Walewska, the Woman Who Changed Napoleon

Maria Walewska may not be a household name like Empress Josephine, but her influence on Napoleon Bonaparte was no less significant. Born to a noble Polish family, Maria became entangled with the French emperor at a time when her country’s fate hung in the balance. Her affair with Napoleon wasn’t just a passionate romance; it was a suave political maneuver.

Who Was Maria?

Portrait of Maria Walewska, 19th century. Source: Get Archive

Maria hailed from the Polish countryside, born into the noble but somewhat humble Łączyński family on December 7, 1786. The family, while ancient by title, was not exactly swimming in riches—unless one counts the modest holdings that barely kept up appearances. Maria, however, was not destined for a life of quiet obscurity. She was the eldest of six siblings, which made her the family’s brightest hope for securing a prosperous future (I’m the oldest and the wittiest and the gossip in Poland is insidious, anyone?). That future came in the form of a certain Count Athanasius Walewski—a man four times her age and on his third marriage.

Maria, still a teen but urged on by her pragmatic mother, took the plunge into holy matrimony with the 60-something Walewski. In doing so, Maria secured her family’s financial future. Walewski, for his part, was a man of wealth and stature—one of the great houses of Poland—but even his lofty title could not disguise the fact that his days of romanticism and courtship were long behind him. It was, as so many marriages of the time were, a union of necessity, not passion.

Maria Walewska’s Coffin Plaque. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Just six months into the marriage, Maria bore a son, Antoni Rudolf Bazyli Colonna-Walewski, though rumors whispered that this child was perhaps a product of earlier indiscretions, conveniently timed to save her honor. The baby boy was swiftly whisked away by Walewski’s meddlesome family, as though Maria was unfit for the duties of motherhood. With her son under the care of older, unwelcoming in-laws, Maria found herself quite alone, in a loveless marriage with little to occupy her thoughts. It is here that historians theorize her patriotism and bent toward Polish independence bloomed in the dark.

Maria’s Poland was a country that had all but disappeared from the map, carved up by ambitious neighbors. Maria’s heart belonged not to her husband, but to the cause of revolution, and it was this fervent patriotism that would soon change the course of her life—and Europe. This is where it gets interesting and where many a researcher has asked themselves: How did this shy, dutiful, if solemn countess end up catching the eye of the most power-hungry man in the world?

How Did She Meet Napoleon?

The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries, by Jacques-Louis Davids, 1812. Source: Google Art Project

In Maria’s world, this is where fate and power collided. In the winter of 1806 Napoleon Bonaparte—fresh from his military triumphs and political machinations—made his grand arrival in Poland. Warsaw itself was as abuzz as the heart of high society.

But let us not fool ourselves into believing this was some whirlwind romance of the usual sort. No, Maria Walewska did not simply flutter into Napoleon’s arms like some lovesick dove. Their first meeting, depending on which version of the tale you prefer, took place in the modest surroundings of Błonie or perhaps Jabłonna, towns that sound far less glamorous than the salons of Paris but were nonetheless filled with intrigue. Maria, ever the dutiful wife and patriot, was hardly swept off her feet by Napoleon’s power or charm. Indeed, she spoke to him briefly and found their encounter rather unremarkable—certainly not the stuff of grand love stories. And yet, Napoleon, ever one to notice the finer things in life, did not forget her.

It wasn’t long before the Emperor, whose thoughts rarely strayed from either conquest or courtly pleasures, sought her out once more—this time in Warsaw, at a ball hosted by Count Stanislaw Potocki. Balls were not simply for dancing in those days. They were political stages where alliances were forged, promises whispered, and, in Maria’s case, decisions of national consequence were weighed.

Maria had no intention of being anyone’s mistress, let alone the Emperor’s but try to imagine the pressure on one lonely, probably bored, patriotic countess. It came from all sides: General Duroc, the Emperor’s Grand Marshal, Polish aristocrats, even her own husband. Their strategy was that by surrendering herself to Napoleon, Maria might influence him to help Poland regain its independence.

Stanislaw Kostka Potocki, by Anton Graff, 1785. Source: Museum of King Jan III

Reluctant but determined, Maria made a choice. She would sacrifice her personal dignity for the cause of her beloved Poland. As she would later write in her memoirs, “The sacrifice was complete.” After that glittering ball in Warsaw, Maria embarked on an affair that would soon become one of the most whispered-about scandals in all of Europe.

This was no ordinary tryst. Napoleon, ever the strategist, kept their meetings the utmost secret. By day, Maria remained the respectable Countess Walewska, but by night she would slip into the Royal Castle to meet the Emperor in his chambers. Their affair progressed behind closed doors, even as the city’s elite speculated with relish on what was a well known secret. How very convenient it must have been for the aging Count Walewski—his young wife now the confidante of the most powerful man in Europe, with political favors hanging in the balance, her rising star leading to more connections and more wealth.

Agar Adamson dressed as Napoleon, 1898. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Their love story, if one dares to call it that, soon took the young woman beyond the borders of Warsaw. Maria followed Napoleon to his field headquarters at Finckenstein Palace, where they lived in adjoining apartments, their not so secret affair continuing under the watchful eyes of courtiers and soldiers alike. Maria, ever conscious of propriety, refused to leave her quarters for fear of being seen. One must wonder whether it was modesty or the fear of gossip that kept her so confined in this Northern Polish outpost. Either way, her resolve to remain unseen did not dampen the fervor of their relationship—or Napoleon’s affection.

As the months passed, the stakes grew ever higher. Maria followed Napoleon on his campaigns, including to Vienna, where she stayed near Schönbrunn Palace while he conducted the business of running his growing empire. It was here, adjacent to the grandeur of the Austrian court, that Maria became pregnant. She returned to Poland to give birth to a son, Alexandre Joseph, a child who was legally recognized by her elderly husband, Count Walewski, but was undeniably Napoleon’s. After all, her husband had been nowhere near her during the time the baby would have been conceived.

It was in this instance, more than ever, that Maria Walewska’s life became bound to the fate of Napoleon Bonaparte—not by love, but by duty. Maria’s legacy was secured. Some called her a mere mistress, sure, but her own people saw her as a patriot who played her part in the ever-turning wheel of history, never letting the world forget the plight of Poland.

Did She Cause Napoleon’s Divorce and Remarriage?

Empress Josephine, 1888. Source: Look and Learn

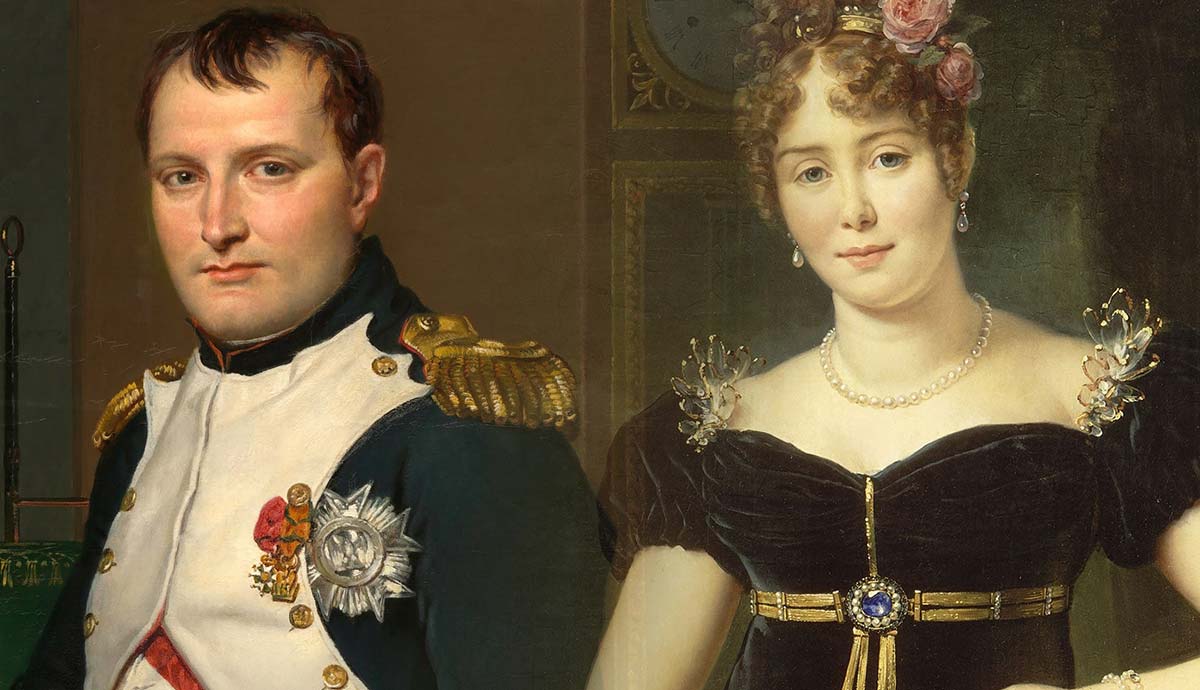

Did Maria Walewska cause the grandest divorce in European history? As with any courtly drama, the answer changes depending on who you ask. By 1809, Napoleon’s once all-consuming devotion to Josephine had cooled—though the story of how it unraveled is woven with heartache, political necessity, and the timeless quest for a legitimate heir. Josephine, for all her charm, grace, and savvy, could not give him the one thing he needed to secure his dynasty: a child of his own.

It is hard not to see Maria’s pregnancy and the birth of a healthy son as the catalyst for Josephine’s downfall. By this point, Napoleon had taken Maria as a mistress—a political maneuver just as much as it was a romantic one. Napoleon’s ability to compartmentalize his personal feelings to better fortify his political ambition was never more evident. Maria, young and beautiful, gave birth to his son, a fact that only further proved that the infertility in Napoleon’s marriage lay not with him but with Josephine.

Yet, Josephine’s infertility wasn’t simply a personal issue—it was an empire-threatening flaw. Napoleon, who had recently crowned himself emperor of the French, understood that dynastic continuity was everything. His siblings constantly urged him to set Josephine aside, and though he resisted for years, Maria Walewska’s pregnancy may have given him the final piece of evidence that led him to make the ultimate decision. If a mistress could give him an heir, then it was beyond time for France’s empress to do the same.

Joséphine de Beauharnais, by Andrea Appiani, 1808. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The divorce itself was more dramatic than any of Josephine’s famous lovers might have foreseen. Napoleon, deeply conflicted and still caring for his wife, hesitated again and again, often sending intermediaries to break the news. Josephine, ever the savvy survivor, must have sensed the rising tide against her. Her anxiety reached its peak when, in 1809, Napoleon made it clear that she wouldn’t be joining him on his military campaign in Austria. Instead, he was accompanied by none other than Maria Walewska, whose pregnancy was now visible for all to see.

When the moment of truth came at the Tuileries, Josephine, ever able to play a part, collapsed in a fit of sobs. Napoleon, awkward and unsure how to handle a weeping woman—a far cry from issuing commands on the battlefield—was forced to carry her to her chambers and away from the eyes of the gossiping courtiers. He may have led armies to victory, but dealing with this woman’s emotional turmoil was another matter entirely. It wasn’t that he didn’t care for Josephine, but his sense of duty to France outweighed even his personal loyalty to the one whom he once called “my adorable friend.”

On December 14, 1809, the official divorce was announced to the people. Napoleon gave a public statement, full of gratitude for Josephine’s companionship and tender words about her years of devotion. Josephine, her voice trembling, attempted to read her own prepared statement but couldn’t get through it, leaving it to an attendant to finish. It was, in every sense, the end of an era. Josephine left for her chateau at Malmaison in the rain with her belongings in tow, including her beloved parrot, no doubt aware that she was leaving behind more than just her imperial status.

Maria Walewska, by Francois Gerard, 1810. Source: BnF

But was Maria truly to blame for all of this? Maria’s role in this part of Napoleon’s life was significant, but she was only part of the equation. The pressures of empire, the need for an heir, and the relentless urging of Napoleon’s family who had never warmed up to her all conspired against Josephine. Maria Walewska merely happened to be the woman who proved that Napoleon could indeed father children and, in doing so, she tipped the scales.

In the end, Napoleon’s divorce wasn’t about love or betrayal—it was about his political gains as a single emperor on the marriage market. Josephine, who had been Napoleon’s “good luck charm,” remained a cherished figure in his life even after the divorce. The two would exchange frequent letters, sharing each other’s secrets and dreams despite being apart. However, the demands of the crown ultimately came first. As for Maria Walewska, she played a role in this drama, but it was the winds of fate and the demands of hereditary inheritance that sealed Josephine’s fate. If it hadn’t been Maria, it may very well have been another young woman whose swollen belly led to the imperial divorce.

Did Maria Love Napoleon?

Napoleon I, Marie Louise of Austria and the king of Rome in the Gardens of the Tuileries, 19th century. Source: Picryl

Maria Walewska and Napoleon—a love story for the ages or merely another chapter in the emperor’s long list of conquests? Take a look at the situation surrounding their bond and examine what evidence history has left behind.

In the wake of Napoleon’s first abdication in 1814, Maria did not hesitate to rush to Fontainebleau. Was it out of love, duty, or perhaps a concern for the four year old son they shared and the security of his estate? Whatever the motivation, Maria’s arrival was met with cold indifference. Napoleon, sulking in his self-imposed isolation, refused to see her. The emperor, once so in control of his empire and image, was now helpless, unwilling to confront the ghosts of his past—even when they came to his doorstep in the form of his former lover.

Napoleon’s Abdication at Fontainebleau, by Paul Delaroche, 1845. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Yet, Maria was nothing if not pragmatic. When Napoleon was exiled to the island of Elba, she sent him a letter—this time not filled with declarations of love, but a polite request for assistance in reclaiming her son’s confiscated lands. If Napoleon had expected a love note, he would have been sorely disappointed. Perhaps, in the midst of his much lessened prominence, he still appreciated a strategist and, despite the letter’s businesslike tone, he invited her to visit him on the island. It could have been nostalgia or he may have harbored the hope of rekindling some old spark. Either way, Maria accepted.

On a moonlit night in September 1815, Maria arrived in secret, bringing with her not just memories, but her young son and family. Napoleon himself met her, escorting her to a remote convent where he had pitched a tent in the garden to receive her—one imagines, with the same pomp and drama that had always characterized his life. The visit, much like their affair, was fleeting. Maria and her party stayed for only two days before leaving as discreetly as they had come. The island buzzed with rumors of their rendezvous, though what truly transpired between them remains a mystery. Did they speak of love, of politics, or simply exchange polite pleasantries and congratulate each other over their growing son.

Propaganda of Napoleon, 1814. Source: Rijksmuseum

After that, their meetings became rare. Maria would see Napoleon only one final time, at Malmaison, following his crushing defeat at Waterloo. By then, both had moved on—at least in the physical sense. Maria had remarried, this time to Philippe-Antoine d’Ornano, a man deeply in love with her and, conveniently, a cousin of Napoleon. If Maria was looking to finally carve out a life free of the emperor’s shadow, d’Ornano’s security and affection seemed to offer that escape.

Did she love Napoleon like a Polish Juliet to his overinflated Romeo? The evidence is as muddled as their relationship. Maria may have cared for him, enough to visit him in exile and offer support when the rest of Europe spat on his name. Her actions could also suggest a woman who was acutely aware of the precariousness of her own position and how her standing and her son’s hinged on Napoleon’s decisions. Her letters, more practical than passionate, show that she never lost sight of her son’s future or her own position within the volatile political landscape.

Philippe-Antoine d’Ornano, by Jean-Adolphe Beaucé, 1863. Source: BnF

Perhaps it was love, but love of a different kind—a love mixed with duty, respect, and ambition. Maria Walewska was no naïve girl swept away by the charms of a powerful man, though she may have been fresh faced and youthful when their trysts began. She was a shrewd woman, navigating the treacherous waters of Napoleonic Europe with a certain mystique and intelligence. If she loved Napoleon, it was with the understanding that their relationship was always bound by more than mere affection.

In the end, Maria’s final years were spent with d’Ornano, a man who adored her and had asked for her hand several times before she accepted his suit. Tragically, her life was cut short at the age of 31, after a failed recovery from giving birth to d’Ornano’s son. Whether or not she loved Napoleon is a question for the ages, but one thing is clear: Maria Walewska played her role with remarkable finesse, forever etched in history as more than just a lover, but as a woman of her own making.

What Happened to Her Son and to Herself?

Tomb of Maria Walewska. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In accordance with her wishes, Maria’s body was returned to her home village of Kiernozia, Poland, where she was laid to rest in the crypt of Saint Margaret’s Church. Her heart, however, stayed in France, interred in the d’Ornano family chapel at Père Lachaise Cemetery to remain close to her beloved final husband. Even in death, Maria remained tied to both the lands and loves of her life—divided between Poland and France.

Maria’s legacy lived on through her three sons, each carrying a piece of her story into the future. Her first son, Count Antoni Rudolf Bazyli Colonna-Walewski, was born during her marriage to her first husband, Count Athenasius Walewski. While Antoni never reached the political heights of his half-brother, he carried the noble Walewski name and heritage forward in Poland.

As for her son with Napoleon, Alexandre Walewski, his life carried on in the vein of both his parents. Born in 1810, Alexandre was not just a footnote in the tale of his powerful father and breathtaking mother. He became a prominent French politician and diplomat, following in the footsteps of Napoleon’s ambition, though perhaps with a bit more decorum. He fought in the Polish insurrection of 1830 and later embarked on a diplomatic career that took him across Europe.

In 1855, he was appointed France’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, a role that solidified his position as a key figure in the Second Empire. Like his father, Alexandre’s life was filled with a certain dramatic flair, whether it was his gambling escapades or his participation in high-stakes matches of political tug of war.

Count Alexandre Walewski, 1865. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Though Maria did not live to see her son’s successes, her influence was undeniable. Alexandre, the son of an emperor and a Polish noblewoman, moved between worlds with ease, much like his mother had done before him. He became a Prince, by decree of Napoleon III, a title that carried with it the weight of his heritage. He was, in many ways, a living bridge between the finer Polish nobility of his mother’s side and the imperial ambitions of his sharp father’s.

Maria’s third son, Rodolphe-Auguste d’Ornano, was born from her brief second marriage to General Philippe d’Ornano, a distinguished officer in Napoleon’s army and Napoleon’s cousin. Rodolphe-Auguste went on to become a French politician, much like his elder brother Alexandre, continuing the family’s tradition of service and public life. Though Maria did not live to see it, her sons ensured that the Walewska and d’Ornano names, as well as her own, would not fade into obscurity.

Her line lives on, not just through her descendants but also in unexpected ways. In 1971, the Pani Walewska brand was introduced, one of Poland’s most iconic cosmetics brands, named after the Polish aristocrat who had once captivated the Emperor of France. The brand, still in production today, serves as a glamorous nod to Maria’s enduring legacy—a symbol of beauty, grace, and the lasting impact of a woman who walked the halls of power with both hidden patriotism and enviable finesse.