www.thegospelcoalition.org

Have We Ever Been Woke?

“The owl of Minerva flies at dusk.” That was Hegel’s way of saying that wisdom, especially when it comes to the interpretation of history, is only possible at the end of the day when everything has happened and we’ve had time to reflect on it.

Coming to terms with the significance of world events is almost impossible in real time. We’re limited by our emotions, our hopes and fears, our awareness of what’s taking place, the outsize narrative-shaping influence of those in power, and our ignorance of the future consequences—and those limitations mean that it can take years for a considered judgment to be possible. That’s why people love to quote the former Chinese premier Zhou Enlai, who was asked in 1972 about the effects of the uprising in France four years earlier and replied, “Too early to say.” Quite right. Cold takes are better than hot takes.

So it’s fascinating that the last 12 months have seen the release of two books that, in different ways, try to make sense of the social and cultural upheavals in Western democracies that peaked in the summer of 2020. (The terminology we use for these upheavals is highly contested: depending on who we are and whether we approve of them, we might talk about the rise of social justice, antiracism, identity politics, cancel culture, racial reckoning, intersectionality, the Great Awokening, or something else.)

Thomas Chatterton Williams’s Summer of Our Discontent: The Age of Certainty and the Demise of Discourse is a historical and journalistic account of what happened, telling the story of 2008 to 2024 with a focus on the response to George Floyd’s death in 2020. Musa al-Gharbi’s We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite takes a sociological and theoretical approach, defending its provocative thesis using established categories from economics, anthropology, sociology, and philosophy.

There are obvious similarities between the two books. Both are serious-looking hardbacks from prestigious presses (Knopf and Princeton). Both are well-produced, carefully researched, and blurbed by the kinds of people you’d expect: David Brooks, Jonathan Haidt, Tyler Cowen, Yuval Levin. Both are brightly and engagingly written, with an audience of thoughtful nonspecialists in mind. Both criticize many of the developments they describe but are eager to understand rather than merely denounce them. Both, significantly, are written by men of color in their early 40s who are fiercely critical of the populist right and cannot be dismissed as part of a racial backlash. And both are excellent: thoughtful, readable, provocative, and illuminating.

Hopeless Summer

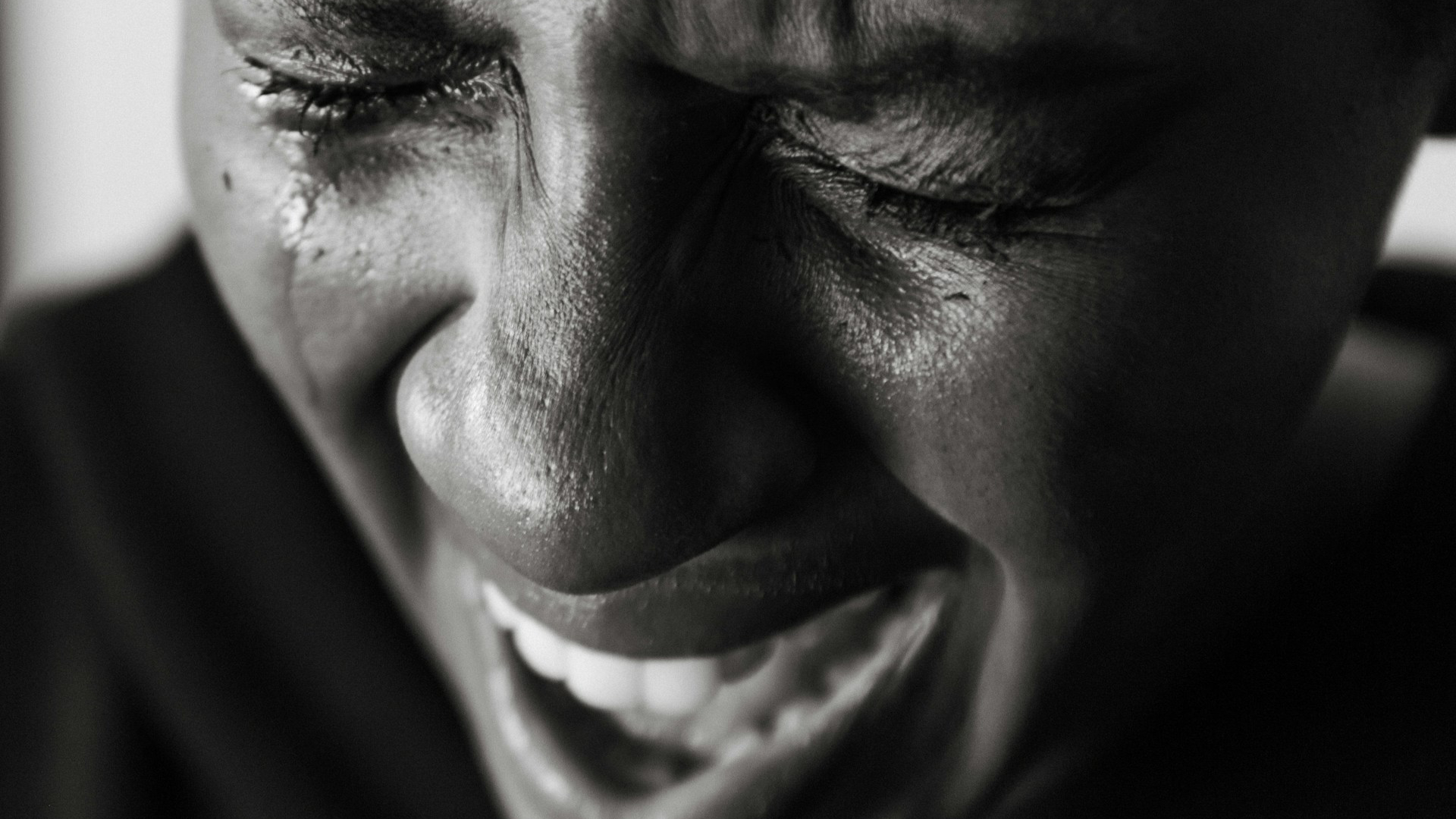

Summer of Our Discontent begins on May 25, 2020, with Floyd’s murder. The event is horribly familiar: a white policeman kneeling on the neck of a black man for nine and a half minutes until he asphyxiates, captured on camera and instantly broadcast for the world to see. But Williams frames it in an unfamiliar and important way. “George Floyd was a poor man. That was the most salient fact about his life” (xiv). “George Floyd was not simply or even necessarily killed on account of race . . . his death was very much a function of his being impoverished. He died over a counterfeit banknote the vast majority of black people would never come to possess” (77).

Indeed, Williams argues, it can be helpful to distinguish between two Floyds: the complex real one and the simplified totemic one. “On the one hand, there was the son and the brother, certainly down on his luck that long weekend, unemployed and carrying methamphetamines and fentanyl in his system . . . dozing in a parked car, having passed a counterfeit banknote moments earlier” (4). “On the other hand, there is the immortalized George Floyd, whose death exists in footage, on wretched loop in our brains . . . the idea, simmering for years without reaching a rolling boil, of intransigent black pain and suffocating white supremacy” (5).

Within minutes of his tragic death, the former was almost entirely swallowed by the latter. Within hours, it was being felt and understood in explicitly Christlike ways:

Had Floyd not, in some viscerally apparent way, borne the awful weight of his society’s racial sins on his very own neck and shoulders? And had that weight—all of ours massed and taken together—not in turn crushed him? A man died for us on that squalid pavement, not asking why his father had forsaken him but, shatteringly, calling for his deceased mother. The lethargic executioner . . . had washed his hands of the matter—had buried them deep inside his pockets. (7)

The following days and weeks saw thousands of protests and millions of people come together in what were probably the largest protests against racism in human history. This raises the obvious historical question: Why?

Williams answers by telling the story of the West from 2008 onward, highlighting four key ingredients.

The first was the global financial crash, which caused large numbers of white millennials—already progressive on sexual ethics and wrestling with colonial guilt about the 9/11 wars—to rethink the merits of global capitalism and consider social democratic or Marxist alternatives.

The second was Barack Obama’s presidency, the start of which was hailed at the time in The New York Times as a “national catharsis” and even the end of the American Civil War, but which could never have fulfilled these colossal post-racial expectations, especially when confronted with regular video footage of young black men being killed by law enforcement.

The third was the way in which Donald Trump’s first term radicalized both the right and the left, from the racist march on Charlottesville to the Jussie Smollett debacle, causing both sides to reject basic liberal norms and ushering in a state of exception.

And the fourth ingredient was COVID-19, which—besides fueling fear, enforcing isolation, increasing inequality, and driving people online—created a new menu of issues for people to disagree about: lockdowns, masks, vaccines, lab leaks, and whether or not it was justified to violate social distancing restrictions in the name of antiracist protest.

Few public figures emerge from Williams’s story with much credit. He’s unsparing in his criticism of Trump, as you might expect, for his general mendacity and ignorance in public office through to his specific suggestions of treating COVID-19 with light-based remedies or injecting disinfectants into people.

But in many ways, he’s even more excoriating about the progressive left’s response to that summer’s events. “In the space of two weeks and without really thinking it through, we went from shaming people for being in the street to shaming them for not being in the street” (78), he explains. We’re still paying the price for that intellectual incoherence today.

Williams devotes particular attention to the “cult of antiracism” that flourished in 2020—from the conceptual work of Robin DiAngelo, Ibram X. Kendi, and Nikole Hannah-Jones to the practical outcomes of institutional repentance in Princeton, policing cuts in Minneapolis, forced resignations at The New York Times, and performative antiracism in Portland—culminating in what CNN notoriously called the “fiery but mostly peaceful protests” in Kenosha after the shooting of Jacob Blake in August.

The book then brings us into the present day, with chapters on the worldwide exporting of American antiracism through social media, “cancel culture,” the spectacle of January 6, and the events in Israel and Gaza since October 2023. Williams has no difficulty in showing that our responses to each of them are colored, often profoundly and sometimes literally, by the summer of 2020.

There’s a lot to like about Summer of Our Discontent. Williams is a good storyteller. His narrative blends familiar set-pieces with unfamiliar details; his prose is fluent and occasionally sparkling; and there’s enough humor to compensate for the relentless grimness of the central arc and the unpleasant memories it’ll evoke for most readers.

The main piece that’s missing, however, is hope: hope that this uncomfortable story means something beyond a collective plague on all our houses, hope that things either have improved or are just about to, hope that we’ve learned anything at all from what happened. (In fairness, this tone is what we’d expect from a book with “discontent” in the title and “demise” in the subtitle.)

Some readers will find it therapeutic to relive that summer in the hands of a confident narrator, safe in the knowledge that we’re all still here five years later. I certainly did. Others, though, will crave positivity: signs of change, a way through, a promising case study, an audacious proposal of some sort. They may need to look elsewhere.

Hypocritical Wokeness

There’s no shortage of audacity in We Have Never Been Woke. In the face of a consensus that the Western world went through a Great Awokening in the 2010s and early 2020s, whether people celebrate or lament it, Musa al-Gharbi calmly but firmly replies, No, we didn’t.

The main piece missing from Williams’s book is hope: hope that things either have improved or are just about to, hope that we’ve learned anything at all from what happened.

Some of us pretended to go through a process of awakening or sincerely believed we had. Others fiercely criticized or ridiculed the awakening and all who sailed in her. But in reality, the so-called Great Awokening never took place:

The problem, in short, is not that symbolic capitalists are too woke, but that we’ve never been woke. . . . Symbolic capitalists regularly engage in behaviors that exploit, perpetuate, exacerbate, reinforce and mystify inequalities—often to the detriment of the very people we purport to champion. And our sincere commitment to social justice lends an unearned and unfortunate sense of morality to these endeavours. (20)

To make this case, al-Gharbi introduces a few pieces of sociological jargon, the most important of which is Pierre Bourdieu’s idea of “symbolic capital.” We all have resources available to us (or not) on the basis of prestige, recognition, honor, and status within a social hierarchy. This symbolic capital may come from our position, credibility, experience, or trust within a particular organization; it may come from academic credentials, the books we’ve read, the degree we hold, the institution we studied at, or the expertise we claim; or it may be cultural in nature, deriving from our speech, clothing, manners, tastes, opinions, terminology, and so forth.

This is vital to understand because “wokeness has become a key source of cultural capital among contemporary elites” (26). One of the main ways in which cultural elites signal their high status, and identify the status of others, is through the positions they hold on issues of race, sexuality, gender, disability, and identity, and the language they use to express them.

Progressive views on issues like these signal high status in polite society, particularly if they’re expressed with the right terminology. But they usually make little practical difference to those they purport to represent and frequently function in self-serving and status-reinforcing ways. “As a result of these tendencies, symbolic capitalists and the institutions they dominate may seem much more woke than they actually are” (36).

Examples of this disparity between appearance and reality abound. Sexually, people who claim to believe that “trans women are women” don’t act that way when it comes to their dating and marriage decisions. Economically, while the Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011 sounded like a grassroots protest against inequality, it was overwhelmingly driven by well-paid graduates in symbolic economy hubs who were generally globalization’s winners, not losers. Racially, those who gain the most from the recent surge in corporate and academic DEI programs aren’t poorer employees or students but the professionals who hold the “social justice sinecures” that teach them (107–110).

Environmentally, the most progressive urban areas in America see less new housing, more aggressive policing, and greater inequality than elsewhere. Romantically, the people who most disparage “traditional families” are among the most likely to have come from such families themselves and to form such families of their own. Financially, affluent progressives give less of their income away to charity than rural, suburban, and religiously motivated conservatives, and their charitable giving is less likely to go to poorer communities.

Everywhere you look, symbolic capitalists are claiming to speak for the poor and marginalized while actually reaping most of the benefits themselves. Consequently, “nonelites would be well advised to ignore what symbolic capitalists say and look at what we do instead” (170).

Everywhere you look, symbolic capitalists are claiming to speak for the poor and marginalized while actually reaping most of the benefits themselves.

Having said that, We Have Never Been Woke isn’t a tirade against progressivism. There’s plenty of posturing and hypocrisy to be exposed, not least in the chapter on totemic capitalism and competitive victimhood. But al-Gharbi doesn’t descend into partisan ranting, preferring to explain rather than to harangue.

He’s clear, for example, that he’s a symbolic capitalist himself, and recognizes that the anti-woke are just as prone to flexing and symbolic posturing as the woke. He considers the similarities between the four periods of “awokening” in the last hundred years—in the 1920s, the 1960s, the 1980s, and the 2010s—and highlights several parallels, which demonstrate that the last decade or so isn’t as unprecedented as we think.

Most importantly, he takes performative wokeness seriously as a sociological phenomenon and seeks to account for it. After introducing the phenomenon of “elite overproduction” (99–103), whereby we educate more graduates than we have jobs for and this causes resentment, he moves on to analyze the emergence of the “creative class” (134–46), and continues right through to the development of “luxury beliefs” (which signal status to the rich but ultimately hurt the poor) and “moral licensing” (in which we hold certain positions to insure us against accusations of racism), tying them together coherently (270–95).

His tone is nuanced throughout, and his argument is supported by empirical research and quantitative data rather than anecdotes, undergirded by a hundred pages of references.

Yet his argument is so clear that this doesn’t involve excessive throat-clearing or punch-pulling. Here’s an excellent example on critical race theory:

Let’s be frank here: the ideas and frameworks associated with what opponents label “CRT” are demonstrably not the language of the disadvantaged and the dispossessed. These aren’t the discourses of the ghetto, the trailer park, the hollowed-out suburb, the postindustrial town, or the global slum. Instead, they’re ideas embraced primarily by highly educated and relatively well-off whites, reflecting an unholy mélange of the therapeutic language of psychology and medicine, the interventionism of journalists and activists, the tedious technicality of law and bureaucracy, and the pseudo-radical Gnosticism of the modern humanities. It is symbolic capitalist discourse, through and through. (274)

This combination of serious research, lucid prose, and tight argumentation characterizes the whole book and makes it a joy to read.

Humble Progress

Neither Williams nor al-Gharbi offers solutions as such. Their purpose is descriptive rather than proscriptive, and there’s nothing wrong with that. But of the two, al-Gharbi comes closer to pointing a way forward, or offering what I referred to previously as hope.

Some of this comes from the books’ respective endings. Where the afterword in Summer of Our Discontent considers the October 7 Hamas attacks and their aftermath, which creates the impression of a permanent doom-loop, the conclusion of We Have Never Been Woke suggests a number of avenues for further study that hint at future possibilities. Some of this difference derives from the time frame. Williams is telling a 15-year story, whereas al-Gharbi is describing a 100-year cycle of which the most recent iteration is just one example. That gives both writer and reader much-needed perspective on a turbulent decade.

And some, it seems to me, comes from the implied anthropology. Summer of Our Discontent describes events that happened to us, on our behalf, in which we as readers were observers at best. We’re watching things unfold passively, with minimal agency of our own; our primary role in remembering is to shake our heads in disbelief at what happened in the corridors of power in Washington, Minneapolis, or The New York Times.

The central figure of We Have Never Been Woke, by contrast, is us. We’re al-Gharbi’s symbolic capitalists, or we wouldn’t be reading a book like this—and a moment’s thought will reveal that we’re characterized by many of the same hypocrisies, status games, and moral inconsistencies. And because both writer and reader are in the same predicament, we can internalize and reflect on al-Gharbi’s implied challenge: Where have we become performative in our activism and self-serving in our moral logic? How, if at all, are we expressing our stated ideals in genuine relationships with those in need around us? Who are they? Are we being careful not to perform our acts of righteousness before men? Or have we received our reward in full?

Where have we become performative in our activism and self-serving in our moral logic?

With five years of hindsight, there’s clearly a widespread sense that the social upheavals that peaked in 2020 went too far. The years since the pandemic have seen a significant pendulum swing in the opposite direction on issues ranging from woke capitalism and cancel culture to unconscious bias training and trans rights. The mood in politics and on social media has shifted substantially in many Western nations.

But there’s another sense in which they didn’t go far enough. Many racial injustices were left largely unaddressed by the mass outpouring of performative wokeness. Many of the changes that did result were cosmetic and served only to enhance the position of more affluent, educated, and privileged groups within society. Many of our poorer and less advantaged citizens are still waiting for a genuine awakening to come. Many of our churches are just as segregated as they were in 2019.

Neither of these books will solve those problems on its own. But both of them, and al-Gharbi’s in particular, have the capacity to challenge and inform us by reframing the narrative of that turbulent year—as long as we read them with a spirit of humility (“Is it I, Lord?”) rather than smugness (“I thank you, Lord, that I am not like that symbolic capitalist over there”). Vibes have shifted many times before. They will again. And thoughtful cold takes on the last one can help us wisely respond to the next one.