api.bitchute.com

All the SHOOTING EVIDENCE points directly to the Biden Administration

All the SHOOTING EVIDENCE points directly to the Biden Administration

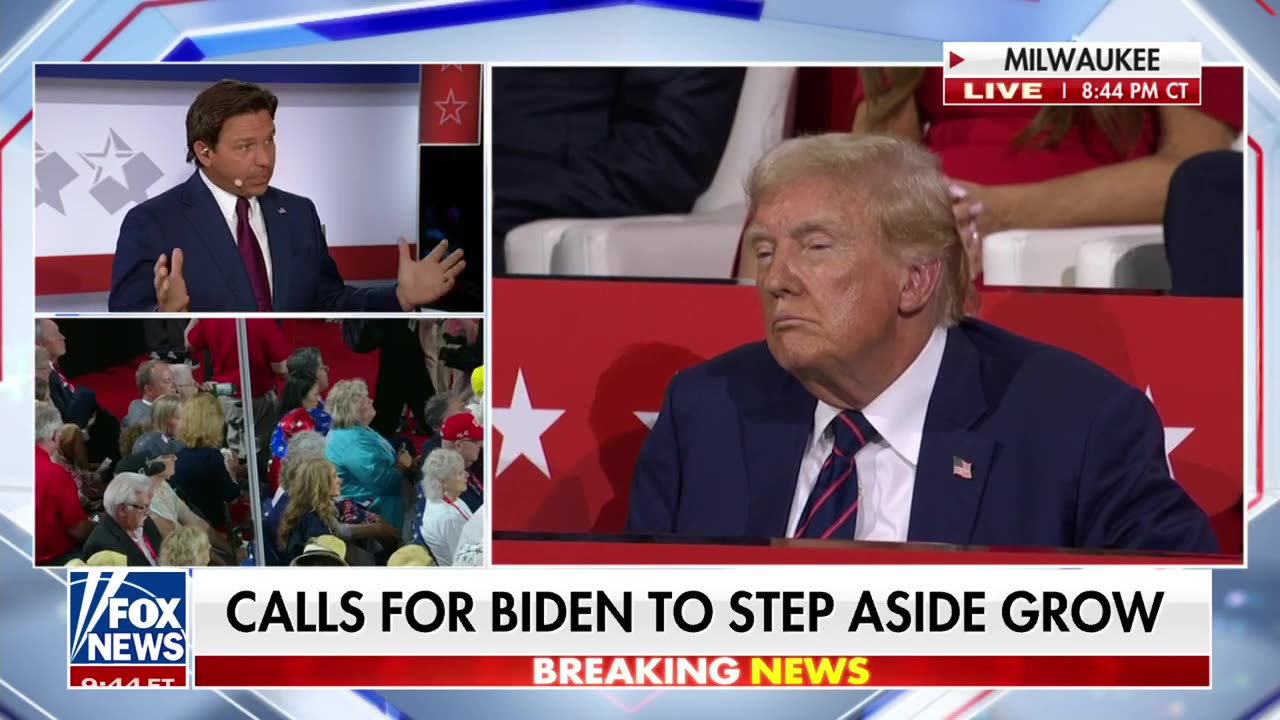

- Assassination attempt on President Trump, blaming Biden administration. (0:03)

- Potential threats to Trump's presidency and how to stay informed and prepared. (6:25)

For more updates, visit: http://www.brighteon.com/channel/hrreport

NaturalNews videos would not be possible without you, as always we remain passionately dedicated to our mission of educating people all over the world on the subject of natural healing remedies and personal liberty (food freedom, medical freedom, the freedom of speech, etc.). Together, we’re helping create a better world, with more honest food labeling, reduced chemical contamination, the avoidance of toxic heavy metals and vastly increased scientific transparency.

▶️ Every dollar you spend at the Health Ranger Store goes toward helping us achieve important science and content goals for humanity: https://www.healthrangerstore.com/

▶️ Sign Up For Our Newsletter: https://www.naturalnews.com/Readerregistration.html

▶️ Brighteon: https://www.brighteon.com/channels/hrreport

▶️ Join Our Social Network: https://brighteon.social/@HealthRanger

▶️ Check In Stock Products at: https://PrepWithMike.com

? Brighteon.Social: https://brighteon.social/@HealthRanger

? Gettr: https://gettr.com/user/naturalnews

? Gab: https://gab.com/NaturalNews

? Bitchute: https://www.bitchute.com/channel/naturalnews

? Rumble: https://rumble.com/c/HealthRangerReport

? Mewe: https://mewe.com/p/naturalnews

? Spreely: https://social.spreely.com/NaturalNews

? Telegram: https://t.me/naturalnewsofficial

? Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/realhealthrangerstore/

Rumble

Rumble