www.thecollector.com

How Julius Caesar Changed Time

Named after the famous Roman general Julius Caesar, who sponsored and promoted its widespread implementation, the Julian Calendar was introduced in 45 BCE, replacing a lunar calendar that had become highly inaccurate. The adoption of a solar calendar represented a significant astronomical and administrative reform that spread with the expansion of Roman territory. It remained the dominant calendar in the Western world for over 1,600 years, when it was replaced by the Gregorian Calendar due to a minor flaw. However, the legacy of the Julian calendar remains ever-present and is still used in some modern churches.

What Preceded the Julian Calendar?

Façade depicting Numa Pompilius, one of the legendary kings of Rome. Source: Louvre

The calendar used across the Roman world before the Julian reform was based upon lunar cycles, rather than solar ones. Whilst this closely mirrored the calendars of some neighboring civilizations, such as the Greeks, other Mediterranean civilizations, including the Egyptians and Carthaginians, used more accurate solar calendars.

In the earliest times, the Romans initially used a 10-month lunar calendar, comprising a total of 304 days, without specific months being linked to any of the seasons. After a reform by the legendary Roman king Numa Pompilius, ostensibly in the 6th century BCE, two additional months were added, after which only minor changes were made to the calendar up until Republican times.

The primary issue with Rome’s lunar calendar was that 12 lunar months reach only 354-355 days, short of the full length of the solar year. Over several years, this causes an increasing misalignment with the natural seasons. Although the Romans attempted to address this by inserting an “intercalary month” called Mercedonius or Intercalaris, towards the end of February, this was not a consistent practice.

Reproduction of the Fasti Antiates Maiores, a painted wall-calendar from the late Roman Republic, c. 84-55 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In fact, especially during the Late Republic, when civil strife and discord became increasingly prominent, priests and their aristocratic patrons could manipulate the calendar for their own political gain. By extending a year, their time in political office could be increased, or their opponents’ time in office could be decreased.

As a result of this often haphazard and chaotic manipulation, between 66 and 46 BCE, the Roman calendar had drifted away from the solar cycle by around 90 days. It was not by accident that this occurred during the dying days of the Roman Republic, when the state was beset by civil wars and the rise of Julius Caesar to the position of dictator.

Month Order

Before Caesar’s Reform (Republican Roman Calendar)

After Caesar’s Reform (Julian Calendar)

1

Ianuarius (January)

Ianuarius (January)

2

Februarius (February)

Februarius (February)

3

Martius (March)

Martius (March)

4

Aprilis (April)

Aprilis (April)

5

Maius (May)

Maius (May)

6

Iunius (June)

Iunius (June)

7

Quintilis (Fifth month)

Iulius (July) — renamed in 44 BC after Julius Caesar

8

Sextilis (Sixth month)

Augustus (August) — renamed in 8 BC after Emperor Augustus

9

September (Seventh month)

September

10

October (Eighth month)

October

11

November (Ninth month)

November

12

December (Tenth month)

December

—

Mercedonius / Intercalaris (intercalary month inserted after February in some years)

— (abolished, replaced by leap day in February)

Inspiration for the Julian Calendar

The Library of Alexandria, etching by O. Von Corvon, c. 19th century. Source: Wikimedia Commons

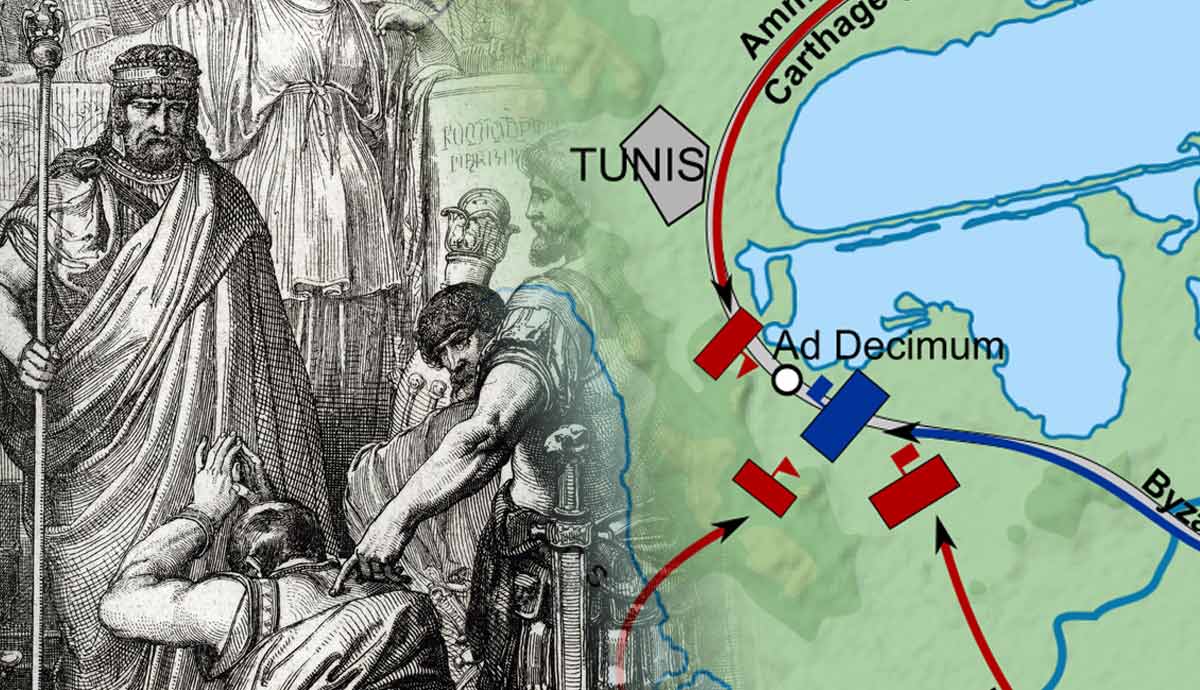

Integral to Julius Caesar’s reform of the Roman calendar was the civil war he fought against his political opponent Gnaeus Pompey, and the political consequences of Caesar’s victory. After their decisive showdown at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE, Caesar followed the fleeing Pompey to the shores of Egypt, where Pompey was killed and his head offered to Caesar.

This left Caesar as the most powerful man in the Roman world by some margin. Within two years, he was granted the extraordinary position of dictator perpetuo. This, along with being Rome’s pontifex maximus or chief priest, put Caesar in a perfect position to make reforms. His decision to reform the calendar was inspired by his time in Egypt.

The Egyptians had a much more accurate method of measuring time, which Caesar began to notice while residing in that region from 48 to 46 BCE. In particular, he was influenced by Sosigenes, a Greek astronomer based in Alexandria, to reform the Roman calendar based on Egyptian models.

The Calendar Reform

Statue of Julius Caesar as Lawmaker and dictator, commissioned in 1696 for the Gardens of Versailles. Source: Louvre

Caesar brought Sosigenes back to Rome with him so that the latter could help correct the chaotic calendar the Roman state had been using. The astronomer calculated the solar year to be approximately 365.25 days, a remarkably accurate estimate for the time.

He also developed the concept of a leap year, adding an extra day every four years to February, thereby helping the calendar stay closely aligned with the seasons. This was accompanied by the standardization of each month to 30 or 31 days, with the exception of February, and the decision to start the year on January 1st, which had previously started on March 1st. These reforms set the calendar in stone and undermined the ability of magistrates and priests to manipulate the calendar.

Finally, to emphasize that this was truly the “Julian” calendar, instigated by Julius Caesar himself, the seventh month, previously called Quintilis, was renamed July in his honor. July was previously called Quintilis, or the fifth month, because the year was considered to start in March. This old system of numbering is still evident in modern month names, including September, October, November, and December.

Cultural and Religious Impact

Saturnalia, by Antoine-Francois Callet, 1783. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The implementation of the Julian Calendar extended far beyond mere administrative reform. It became a powerful instrument of cultural unification across the Roman world. As Roman authority expanded, local timekeeping systems gradually yielded to Caesar’s calendar, creating a standardized temporal framework that helped reinforce imperial cohesion.

As such, religious practice throughout the empire underwent significant transformation, as festivals became permanently anchored to specific dates. No longer did priests need to announce observances; instead, the calendar itself functioned as a sacred text guiding religious life.

Major celebrations like Saturnalia (17th-23rd December) and Lupercalia (15th February) gained enhanced significance through their predictable annual recurrence, fundamentally altering how Romans conceptualized their relationship with the divine.

Julius Caesar by Italian Andrea di Pietro di Marco Ferrucci, 1512-14, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The calendar’s predictability also revolutionized agricultural planning, allowing farmers to schedule planting and harvesting according to relatively fixed dates rather than variable lunar cycles. Scholars have shown how this reliability improved crop yields and food security throughout Roman territories.

In a similar vein, civic administration benefited from the standardized system, with markets, elections, and legal proceedings now operating on a dependable schedule that enhanced economic efficiency.

The calendar thus became more than a method of tracking days. It evolved into a fundamental institution, synchronizing Roman society across religious, agricultural, administrative, and personal domains.

The Calendar’s Subsequent History

Bust of the Emperor Constantine, Roman, c. 4th century CE. Source: Capitoline Museum, Rome

Throughout the imperial period, the calendar became thoroughly embedded in Roman civic and religious life. Provincial governors used it to schedule tax collections, while ordinary citizens planned their lives around its structure. By the 4th century CE, the Emperor Constantine‘s adoption of Christianity initiated the process of overlaying Christian observances onto this established framework, laying the groundwork for its medieval transformation.

When the Western Roman Empire collapsed in the 5th century CE, the Julian Calendar demonstrated remarkable resilience. Unlike many Roman institutions that vanished with imperial authority, this practical system of timekeeping persisted across former territories.

The Christian Church became the calendar’s most important custodian during the medieval period. Monasteries emerged as centres of timekeeping expertise, with monks calculating dates for Easter and other movable feasts through complex tables known as “computus.”

An Early Modern Computus, likely modelled on Medieval precursors, Italy, 1647. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The calendar thus transformed into a more religious framework, with each day acquiring commemorations of saints that created a “sanctoral cycle” overlaying the solar year. By the 9th century, Charlemagne‘s educational reforms had institutionalized knowledge of the Julian Calendar as standard clerical education.

However, despite widespread adoption, regional variations flourished within the calendar’s consistent structure. Different areas adopted various New Year conventions: England preferred the Annunciation style (March 25th), Germany used Christmas (December 25th), while Venice began its year on March 1st. Local saints’ days and harvest festivals further customized the calendar to regional needs while maintaining cross-regional compatibility.

When Pope Gregory XIII introduced his calendar reform in 1582, Eastern Orthodox churches notably rejected the change. The Byzantine Empire meticulously maintained Julian traditions, deeply integrating them into Orthodox liturgical practices. This calendar schism persists to some extent today, with Orthodox Christmas falling on January 7th, rather than December 25th, as used in the Gregorian Calendar.

Why Was the Julian Calendar Reformed?

Pope Gregory XIII, by Bartolomeo Passarotti, 1586. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Pope Gregory XIII’s calendar reform of 1582 emerged primarily from astronomical necessity rather than political ambition. By the 16th century, the Julian Calendar’s slight miscalculation, overestimating the solar year by approximately eleven minutes, had accumulated into a ten-day discrepancy between the calendar date and the actual solar position, disrupting the ecclesiastical calendar’s alignment with seasonal phenomena.

The timing of Easter, calculated based on the spring equinox, had drifted significantly from its intended position, creating theological concerns about proper observance of Christianity’s most sacred feast. Gregory assembled a commission of mathematicians, astronomers, and clerics, led by physician Aloysius Lilius and mathematician Christopher Clavius, to address this growing temporal misalignment.

One of the earliest versions of the Gregorian Calendar printed in 1582. Source: Vatican Library

Their solution proved remarkably elegant: removing ten days from October 1582, with October 4th immediately followed by October 15th, while implementing a refined leap year system that omitted century years not divisible by 400. This modification reduced the calendar’s error to approximately one day per 3,300 years, a dramatic improvement over the Julian system’s drift of one day every 128 years.

Through this calculated intervention, Gregory XIII established a temporal framework that would eventually achieve near-universal adoption, becoming the international standard that continues to regulate global civil and commercial life today.

How Is the Julian Calendar Still Relevant Today?

Onion dome towers of the Russian Orthodox Church of St. Alexander Nevsky and St. Nicholas, Tampere, Finland, 1890s. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Despite being replaced by the Gregorian system, the Julian calendar retains significant cultural and religious relevance in the modern world. Eastern Orthodox communities continue to calculate their liturgical calendar using Julian principles, resulting in the distinctive phenomenon of “dual dating” for major feasts, such as Christmas and Easter, across Christian denominations.

The Julian calendar also retains importance in historical scholarship and genealogical research, as records spanning over 16 centuries, from imperial Rome through early modern Europe, employed this system. Historians must regularly convert between Julian and Gregorian dates when studying primary sources, particularly from regions that maintained Julian reckoning into the early 20th century, such as Russia before its 1917 calendar reform.

Sirius (bottom) and the constellation Orion (right)

Astronomers still use the Julian Day number system, a continuous count of days since January 1, 4713 BCE, for precise astronomical calculations and dating celestial events across vast time scales. This specialized application demonstrates how Julian principles continue to serve scientific needs even as civil timekeeping has moved to more accurate systems.

The Berber people of North Africa and Ethiopian Orthodox communities likewise maintain calendrical practices derived from Julian traditions, illustrating how Caesar’s temporal framework transcended its Roman origins to become embedded in diverse cultural contexts worldwide. This remarkable persistence across millennia testifies to the Julian calendar’s practical utility and cultural adaptability despite its mathematical imperfections.

Bitchute

Bitchute