doyouremember.com

William Shatner’s Thanksgiving Photo Has Fans Stunned, Especially After Recent Health Scare

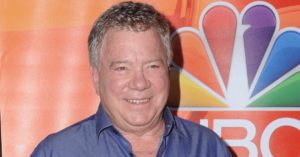

William Shatner sparked a wave of excitement after sharing a new photo on Thanksgiving. The 94-year-old actor looked upbeat and energetic, surprising fans who had worried about him earlier in the year. According to Hello Magazine, the star had been hospitalized in September after a medical emergency involving his blood sugar. The incident raised concerns about his health, but his latest message shows he is doing well.

In the post, William Shatner stood in a bright kitchen, smiling in front of a full Thanksgiving spread. He captioned the image with warm holiday wishes and wrote that he felt “blessed beyond measure with health.” His message reassured fans and immediately sparked conversations about how remarkably youthful he appears at his age.

Fans Praise William Shatner’s Age-Defying Look

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by William Shatner (@williamshatner)

Many fans filled the comment section with amazement. They insisted William Shatner looked far younger than 94 and begged him to share the secret to his energy. One person wrote, “My gosh, I hope I look as good as you at 94! ” Others joked that he must have found the “Fountain of Youth” or keep a portrait aging in his attic. Their playful comments highlighted how impressed they were by his appearance.

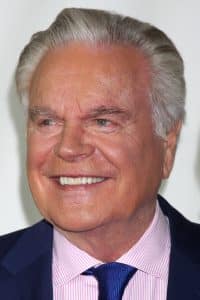

William Shatner/Imagecollect

William Shatner has long been known for his charisma, but his latest photo brought a new wave of admiration. The fact that he appeared so vibrant only months after a health scare made the moment even more meaningful. Fans were relieved, encouraged, and inspired by the positive update.

William Shatner Reflects on His Health Journey

BOSTON LEGAL, William Shatner, ‘The Innocent Man,’ (Season 4, airing Oct. 25, 2007), 2004-08, photo: Scott Garfield / © Fox / courtesy Everett Collection

After his September hospitalization, William Shatner quickly reassured the public that he was fine. He posted a humorous message saying that “rumors of my demise have been greatly exaggerated,” even teasing followers not to trust tabloids or AI. His lighthearted response showed he still carries the calm confidence fans have loved since his Star Trek days.

William Shatner/Instagram

William Shatner has also been open about past health struggles. In 2024, he revealed he had been treated for stage 4 melanoma. Years earlier, he faced a frightening prostate cancer diagnosis. Despite these challenges, the actor remains optimistic. His Thanksgiving message suggests he is grateful, strong, and living with renewed appreciation.

Next up: Robert Wagner Remembers Natalie Wood On 44th Anniversary Of Her Death

The post William Shatner’s Thanksgiving Photo Has Fans Stunned, Especially After Recent Health Scare appeared first on DoYouRemember? - The Home of Nostalgia. Author, Ruth A