www.dailysignal.com

‘Winning Issue’?: Michigan Dems Hope Abortion Will Help Harris Thwart Trump in Swing State

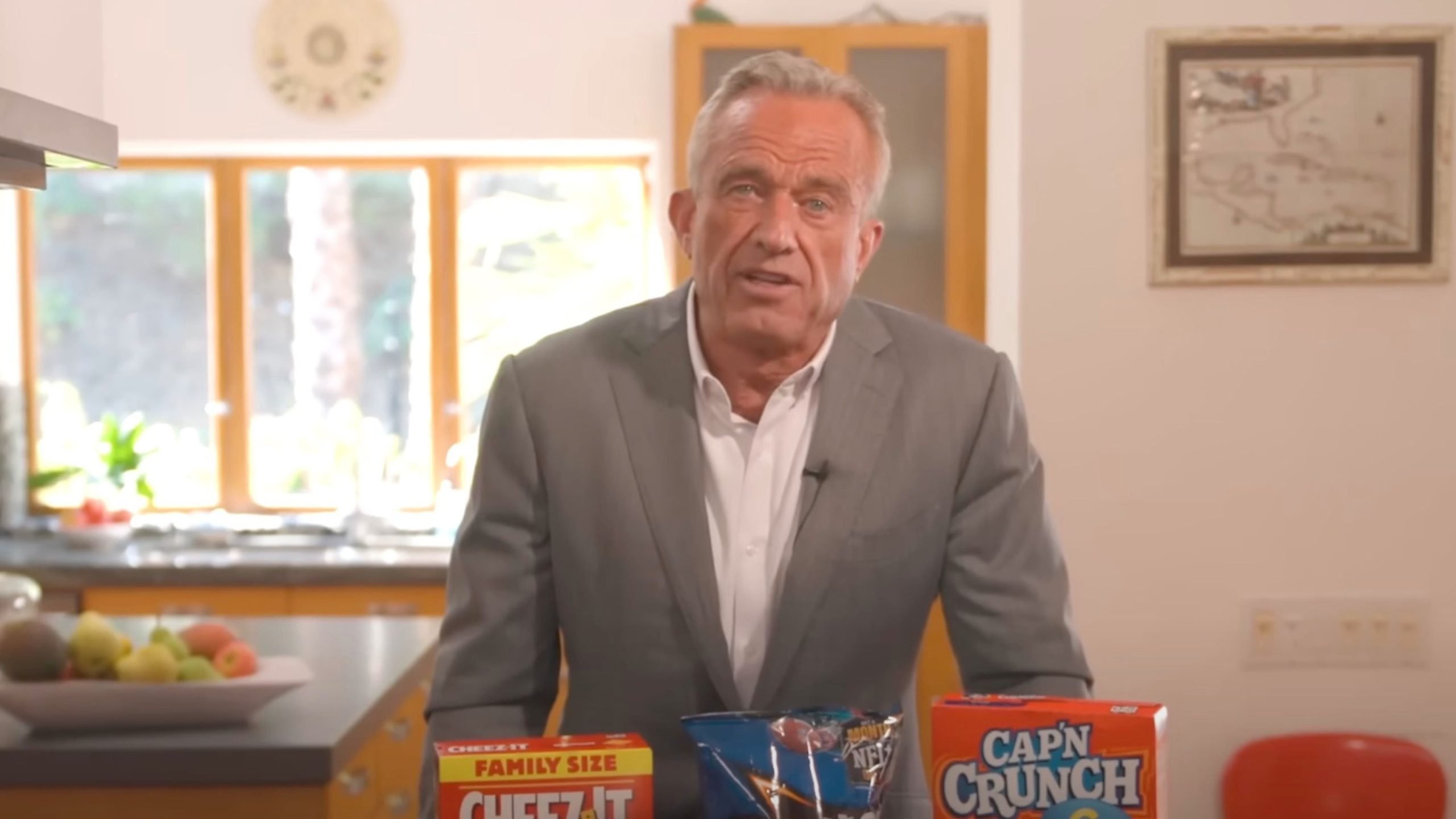

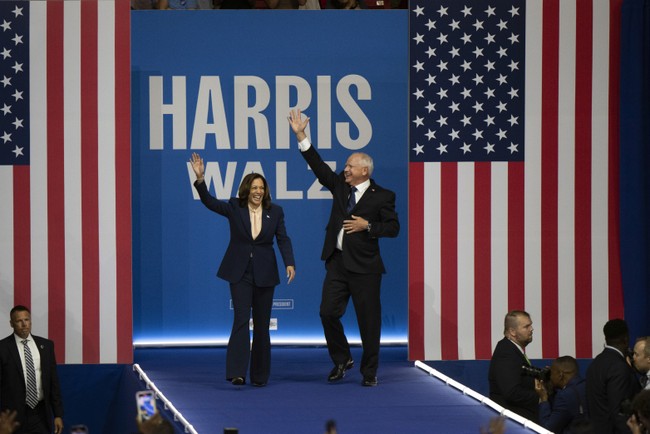

With the Kamala Harris campaign reportedly fearing it will lose Michigan, Democratic strategists in the key Midwestern swing state are placing their hopes on the issue of abortion to give the vice president an edge on Nov. 5.

Democrats participated in a Monday webinar, co-hosted by midwestern lobbying firm Kelley Cawthorne and news service Gongwer Michigan, for clients and subscribers to hear from those working on the November elections.

One of the most hotly contested swing states, with its 15 Electoral College votes, Michigan may determine the outcome of the 2024 presidential election.

Former President Donald Trump continues to hold a one percentage point lead over Vice President Kamala Harris in a two-way race. Trump and Harris are in a dead heat in an eight-way race, which is what Michiganders will see on their ballots, according to an Oct. 16 Mitchell Research & Communications poll.

The Harris campaign fears it can’t win Michigan, NBC News reported.

“There has been a thought that maybe Michigan or Wisconsin will fall off,” a senior Harris campaign official said to NBC, adding that the bigger concern of the two is Michigan.

Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania make up the “blue wall,” which have delivered the win to the last two Democratic presidents.

In the Monday webinar reviewed by The Daily Signal, Celinda Lake, the founder of Lake Research Partners, a liberal Democratic political strategy research firm, said she thinks it will be hard for Democrats to win on the economic issue because voters “give a lot of credibility to Republicans” on it, especially since Trump is a businessman.

As a result, she recommended Michigan Democrats zero in on abortion.

“The formula for success is to be even on the economy and win on abortion, honestly,” Lake said.

Lake told The Daily Signal she didn’t say abortion is “more important” than the economy, but that it’s a “clear distinction.”

“It’s important to have [an] economic argument, too,” Lake said in an email. “[Michigan] is close, but with the demographics and women leadership, I think we will win.”

The economy ranks as the most important issue to voters, according to a Gallup poll conducted Sept. 16 to 28.

The current 52% of voters rating the economy as an “extremely important” influence on their vote for president is the highest since October 2008 amid the Great Recession.

Voters view Trump as better able to handle the economy than Harris by 10 percentage points. Harris holds a 16 percentage point lead on Trump for how she’d handle abortion.

“Abortion is a clear distinction, like who’s really good on inflation policy or rising cost of living, is hard for people to sort out,” Lake said.

Michigan Democratic State Rep. Penelope Tsernoglou said abortion is a “winning issue” on the ballot.

“I think everyone knows it’s a winning issue, which is why even Trump keeps trying to suggest that he supports choice,” the Michigan state lawmaker said. “I mean, time and time again, he keeps suggesting that he is, you know, in some way pro-choice, which is completely false and not true. But polling, you know, does tell us that choice is a very important factor in how people are choosing their leaders now.”

Tsernoglou did not respond to The Daily Signal’s request for comment.

Trump has said abortion restrictions are up to the states, and he does not support a national ban on abortion.

“My view is now that we have abortion where everybody wanted it from a legal standpoint, the states will determine by vote or legislation, or perhaps both, and whatever they decide must be the law of the land,” Trump said in a video posted to social media.

Zach Gorchow, president of Gongwer Michigan, the Michigan-based news service that sponsored the webinar, said Democratic candidates throughout the country are putting a heavy emphasis in their messaging on protecting abortion rights.

In TV ads, Democrats say that “the Democratic candidate will protect a right to an abortion, the Republican candidate will not and may even favor the old, now-repealed law that criminalized it,” Gorchow said.

Gorchow moderated the webinar on behalf of Gongwer Michigan. He moderated a Republican strategy panel sponsored by his organization a few weeks ago.

Gorchow told The Daily Signal he believes abortion is “a helpful piece of the puzzle” for Democrats, “given that Michigan voters by a 57-43 margin voted to legalize abortion in 2022, and [the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision that overturned Roe v. Wade] helped propel them to control of state government for the first time in 40 years.”

“But candidates for statewide elections, to be successful, generally have to emphasize multiple issues. Michigan is a diverse state and generally rolling with a single-issue message does not work,” he said.

Michigan passed Proposal 3 in the midterm elections, which added an amendment to the Michigan Constitution allowing abortion throughout pregnancy if necessary to protect a woman’s “life or physical or mental health.”

Lake said Michigan Democrats should use the abortion issue to win over young women, who she presented as crucial for a Harris win in the Great Lakes State.

She said that young women turned out in record numbers in Kansas after the June 2022 Supreme Court Dobbs decision.

“Young women have been very motivated by abortion,” Lake said.

Still, she said, “we have got to work” to get young women to the polls, particularly “low-propensity” women who are eligible to vote, but who have a history of infrequently doing so.

According to Lake, it’s likely that there will be a “Trump surge” among young men who were registered to vote, but chose not to do so in the 2020 election. She said young women and blacks have the potential of creating a “Harris surge.”

Lake said that Democrats must have clear, direct messaging on abortion to help “mobilize” voters to go to the polls in November.

“People have just taken extreme, extreme positions,” Lake said, “and the clarity of this issue really helps to mobilize Democrats and young women.”

The post ‘Winning Issue’?: Michigan Dems Hope Abortion Will Help Harris Thwart Trump in Swing State appeared first on The Daily Signal.