www.dailywire.com

Morning Brief: Kirk’s Historic Memorial, Democrat Defiance, & The Palestinian State Push

People from all over pack Arizona’s State Farm Stadium to honor Charlie Kirk, Democrats resist a Kirk resolution, and several countries break with the United States and move to recognize a Palestinian state.

It’s Monday, September 22, 2025, and this is the news you need to know to start your day.

Morning Wire is available on video! You can watch today’s episode here:

If you’d rather listen to your news, today’s edition of the Morning Wire podcast can be heard below:

Kirk’s Historic Funeral

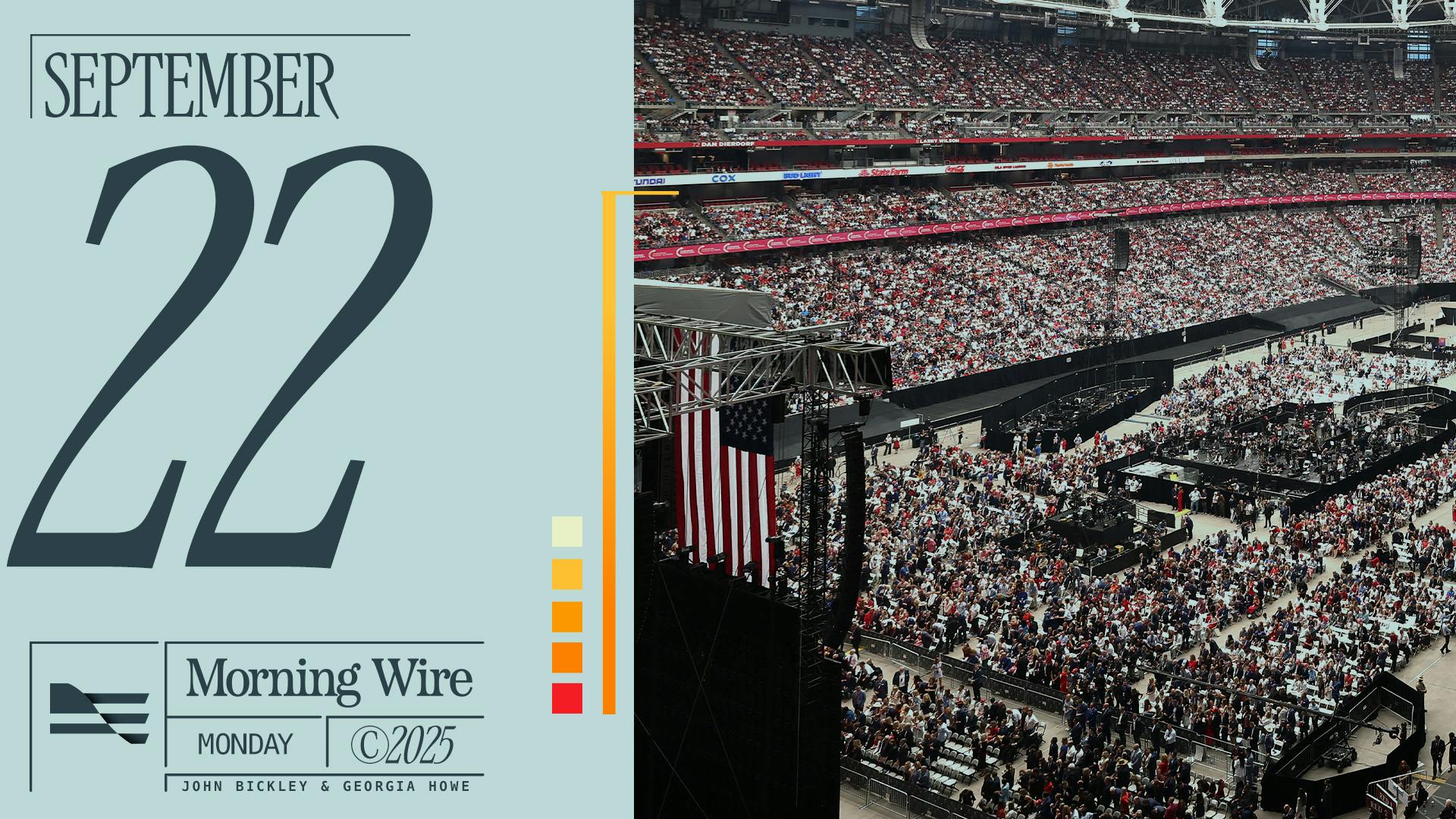

Topline: President Donald Trump joined hundreds of thousands of Americans in Arizona on Sunday to celebrate the life of Charlie Kirk.

An estimated 200,000 people descended on State Farm Stadium in Glendale, home of the Arizona Cardinals, for a final memorial service honoring the conservative activist. For a private citizen, drawing a crowd of that magnitude is nearly unprecedented.. It could be the largest funeral turnout since Martin Luther King Jr. back in 1968 — that event drew 300,000 people.

Mourners, who were encouraged by Turning Point USA to wear red, white, and blue, came from all over the world. Some camped out for 48 hours to get in.

The Lineup: The morning started with an extended time of worship led by Christian music stars Phil Wickham, Kari Jobe, Brandon Lake, and Chris Tomlin.

Charlie’s pastor, Rob McCoy, then shared personal stories before offering a chance for attendees to put their faith in Jesus and become Christians. Hundreds of attendees stood up and proclaimed their new faith.

The speaker list included a who’s who from the Trump administration, including Vice President JD Vance, Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., War Secretary Pete Hegseth, Secretary of State Marco Rubio, and President Trump, whose family says viewed Charlie as another son.

Trump said of Kirk’s impact: “On that terrible day, September 10, 2025, our greatest evangelist for American liberty became immortal. He’s a martyr now for American freedom. I know I speak for everyone here today when I say that none of us will ever forget Charlie Kirk, and neither now will history.”

Erika Kirk’s forgiveness: Erika Kirk, Charlie’s wife, gave the penultimate speech honoring her husband before joining the president on stage for a final wave to the audience. Kirk, the newly chosen CEO of Turning Point USA, in front of the packed stadium, offered forgiveness to her husband’s suspected killer.

“My husband Charlie … he wanted to save young men just like the one who took his life … that young man … I forgive him,” she said. “I forgive him because it was what Christ did and is what Charlie would do.”

Divisions Over Kirk And Kimmel

Topline: The past week saw support for Charlie Kirk pour in nationwide, even as criticism from the Left and the fallout over Jimmy Kimmel’s suspension persisted—events that ultimately culminated in a shooting at an ABC station.

A U.S. House divided: On Friday, House Republicans proposed a resolution condemning the assassination of Kirk and honoring his life, saying he “engaged in respectful, civil discourse.” But 118 Democrats did not support the measure.

The resolution was ultimately approved, but not in the unified way that has happened in the past. At the end of June, for example, Republicans unanimously joined Democrats in passing a similar resolution rejecting violence in the wake of the assassination of Melissa Hortman, a Democratic state representative from Minnesota.

Although Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) generally condemned political violence, on the House floor, she urged Democrats to vote against the Kirk resolution. Then, she turned the focus to ABC’s decision to suspend late-night host Jimmy Kimmel for his false remarks about Kirk’s killer.

“All in the name of Charlie Kirk, President Trump and the FCC are now cynically threatening to shut down ABC and any outlets who give airtime to the administration’s political critics. This is a disgusting attack on the American people and the very First Amendment rights that define us as a country,” Ocasio-Cortez said on the floor of the House.

ABC under fire: A few hours later, during a protest against Kimmel’s suspension, 64-year-old Anibal Hernandez Santana allegedly fired three shots into the lobby of a Sacramento ABC station while employees were still working inside. Hernandez is reportedly a former teachers union official whose social media accounts are filled with anti-Trump rants. He was initially taken into local custody and released on bail. But the FBI later rearrested him, so he is now in federal custody.

Dems stand for Kimmel: Democrats and the Left more broadly are more focused on Kimmel’s suspension than Kirk’s assassination. Conservatives have pointed out that The Atlantic has now published more articles lamenting Kimmel being benched than Kirk being killed, for example.

And Democrats’ criticism of Kirk has not slowed. Texas Rep. Jasmine Crockett, on CNN Sunday morning, lambasted her colleagues who voted for the Kirk resolution.

But there have been exceptions. Former Obama official and CNN contributor Van Jones shared that he received a note from Charlie Kirk that he did not find until after Kirk’s death. And it really revealed Kirk’s character.

“We were beefing. We were going at it online, on air, and then, after he died, after he was murdered, my team called and said, ‘Van, he was trying to reach you, man,’” said Jones. “This guy is reaching out to his mortal enemy, saying we need to be gentlemen, sit down together, and disagree agreeably.”

“He was not for censorship. He was not for civil war. He was not for violence. He was for dialogue, open debate, and dialogue, even with me,” he said.

Western Countries Recognize ‘The State Of Palestine’

Topline: That was British Prime Minister Keir Starmer announcing Sunday that the UK is joining Canada and Australia in formally recognizing “Palestine” as a state. The move puts the countries at odds with the United States as the UN General Assembly is set to convene.

Expert opines: Victoria Coates, vice president of the National Security and Foreign Policy Institute at The Heritage Foundation: “This is a recognition so far by Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia of a Palestinian entity. And it means absolutely nothing. It doesn’t have borders. It doesn’t have any of the trappings of a nation-state that we would understand in terms of civic institutions. This is simply an action taken in a multilateral body with no binding legal authority to make the respective prime ministers of those three countries, I guess, feel better about themselves because it’s certainly not doing anything to help the Palestinians.”

Coates on the timing: “They announced it now because the United Nations General Assembly is in session this month. President Trump will be addressing the body on Tuesday, but this is when all the world leaders come together and take these kinds of diplomatic theatrical actions, again, to try to look big on the world stage. But again, there is no binding authority here. This is meaningless.”

“It makes peace less likely because it encourages the Palestinian Arabs to think that they can have it all, that these countries are going to reject Israel and isolate Israel. And one of the things that’s striking to me is this does nothing to help any Palestinian in Gaza. No Palestinian in Gaza will eat because of this. No Israeli hostage will come home because of this. It will simply be, as I said, political theater to make these leaders pander to their very far left bases in all three countries.”